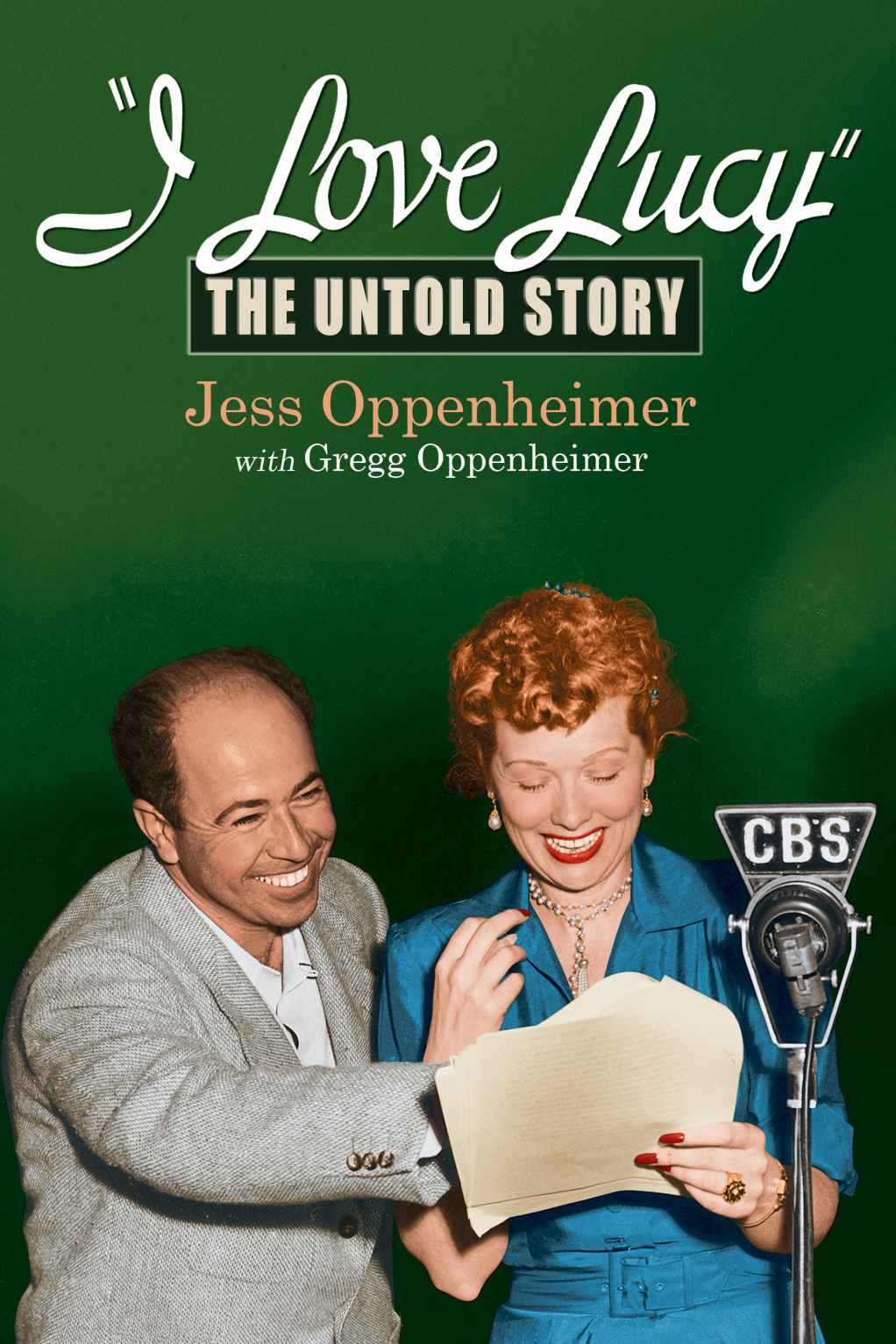

I Love Lucy: The Untold Story

Read I Love Lucy: The Untold Story Online

Authors: Jess Oppenheimer,Gregg Oppenheimer

Copyright © 2011 by Gregg Oppenheimer

All Rights Reserved

Second Kindle Edition 2012

I Love Lucy

and

My Favorite Husband

used with permission of the copyright holder, CBS Inc.

Dialogue from the

Peanuts

characters is from the comic strip drawn by Charles Schulz and syndicated by United Feature Syndicate.

Part One: The Memoir

I Love Lucy: Behind the Scenes

by Jess Oppenheimer

with Gregg Oppenheimer

I Love Lucy: The Untold Story

by Gregg Oppenheimer

I Love Lucy: Behind the Scenes

By Jess Oppenheimer

with Gregg Oppenheimer

O

N

J

ANUARY

19, 1953, Lucille Ball gave birth to two baby boys. One was born in the morning in Los Angeles and the other that night, three thousand miles away in New York City. And if that isn’t amazing enough in itself, try this—one of the babies was conceived eight months before it was born, but the pregnancy lasted only six weeks! I’m referring, of course, to the television baby born to Lucy and Ricky Ricardo.

Of Lucy’s two sons, I’ve always felt a closer kinship with Little Ricky Ricardo. Although I can’t claim to be his father, I feel I’m responsible for his being here.

As producer and head writer of

I Love Lucy,

I was well acquainted with the public’s great fascination for all things “Lucy.” But I was totally unprepared for the overwhelming reaction that met the new arrivals in the Ricardo and Arnaz households.

The TV birth of Little Ricky was watched by an incredible 44 million viewers—15 million more than would tune in President Eisenhower’s inauguration the next day on

all three networks.

And when Lucy delivered Desiderio Alberto Arnaz y de Acha IV by Caesarean section at 8:15 on that Monday morning, the news was immediately flashed over every news service. Programs were interrupted. It was announced in schools.

Seven minutes after Lucy had her baby, it was announced over the radio in Japan—and in many other countries where they had never even seen

I Love Lucy.

Somehow, they were interested.

I wasn’t about to wait for news bulletins. I had arranged

with Desi to phone me at home from the hospital with progress reports. At 7:45 a.m., when Desi called to let me know that Lucy was about to go into the operating room, I asked him to leave the line open so I could be the first to hear the news.

As I sat there in the kitchen, waiting for the word from Desi, I started

thinking about how far we’d come with

I Love Lucy

, and how unbelievably lucky we had been at every step along the way. It seemed incredible that it had only been eighteen short months since all of us had plunged headlong into the brand new business of television. We were an eager and innocent crew, embarking on a trip in a medium about which we knew nothing. None of us had any inkling of the high-flying success that lay ahead. We were all just deliriously knocking ourselves out to put the show on the air each week. What’s more, we loved the work—none of us could wait to get to the set or to the typewriter.

Luck. There was no doubt about it. The show had been singularly blessed with unbelievably good luck from the very moment of its conception. Somehow, the perfect group of special talents had just happened to be available and in the right spot at precisely the right time in history for this particular project. From the first reading of the first script, it was apparent that the kind of material that we most easily and naturally created was right on the button with the entire cast’s sense of humor. They were able to perform it brilliantly with a minimum of effort.

From the initial performance of

I Love Lucy

before the cameras, there had been magic in the air. The audience had fallen in love at first sight, and they acted like giddy lovers, indeed. Once the spell was cast, laughing at the jokes wasn’t enough for them. Soon they started laughing at the straight lines, and then at any line, as long as it came from this particular cast. More than once I had seen “Good morning.

How are you?” knock ’em right into the aisles. It was the audience’s way of saying “I love you.”

Of course, the most important piece of magic was Lucy herself. Her radiant talent, her wonderful combination of beauty and clown, her sure touch for the human quality, which found recognition in every segment of the viewing audience, were the sparks that gave life to the entire series. She was truly one of a kind, and I thanked my lucky stars that our paths had crossed when they did.

Even Lucy’s unexpected pregnancy at the end of our first television season had been a stroke of luck, although at the time it had seemed to spell the end of the series. I had

learned of Lucy’s impending motherhood just as we were about to begin rehearsals for one of the last shows of the season.

Desi had entered the soundstage and, without saying a word, he had come over, put his arm around my shoulder, and walked me off the set and over to my office so we could be alone. I could see from his expression that whatever the news, it could only be bad.

Swallowing hard, Desi said, “We just came from the doctor. Lucy’s going to have a baby.” Pleased as he and Lucy were about having another child, both of them were certain that it meant that

I Love Lucy

would have to go off the air.

The cardinal rule of those who controlled the new medium of television was not to present anything that might offend anyone. The CBS censor had a list of words that could never be uttered on the air, and “pregnant” was one of them. Of course, today we can not only say the word “pregnant” on TV, but also make graphic reference to all the various organs, equipment, and procedures that contribute to that condition—or lack of it. It’s hard to imagine that simply putting a pregnant woman on television could ever have been considered daring. But in the early 1950s, the very thought of a TV show dealing with as real an idea as having a baby was simply unheard of. To Lucy and Desi, it looked as though they would have to quit TV just as they reached the top.

As the show’s head writer and producer, I was the one who had to decide how to save

I Love Lucy.

“What can we do, Jess?” Desi asked. “How long will we have to be off the air?”

Without thinking twice, I grabbed his hand and shook it. “Congratulations,” I said. “This is wonderful! This is just what we need to give us excitement in our second season. Lucy Ricardo will have a baby, too!”

Desi was incredulous. “We can’t do that on television!” he declared. “The network and the sponsor will never let us get away with it.”

“Sure they will, if we present it properly,” I told him. “What better

thing is there for married couples in the audience to identify with than having a baby?”

Desi finally agreed that it was worth a try, and ran off to tell Lucy the news that she was going to have two babies. But as soon as the door closed behind him, I started wondering if I shouldn’t have thought twice before making that decision. The responsibility of doing a series of shows on such a delicate theme, in such an intimate medium, with a star who was actually pregnant, was staggering.

And maybe Desi was right about the sponsor and the network. After all, they had already made it clear to us that the Ricardos, though

married, were not even allowed to share a double bed!

I quickly called a conference with my cowriters, Madelyn Pugh and Bob Carroll, Jr. The three of us sat in my office for hours, discussing every angle of the problem. We finally decided that although it had never been

done before, we were prepared to tackle it. We felt certain that we could extract all the inherent humor from the situation while staying well within the bounds of good taste.

And now, eight months later, I was satisfied that we had succeeded in doing just that.

As I sat there still holding the phone, a sobering thought suddenly hit me. Television, still in its own infancy, was about to give birth to its first baby, and I was responsible not only for its being born, but also for the way in which it would be brought up. Of course, I was not altogether

without experience on this score—my own two young children, asleep upstairs, were proof of that—but unlike what went on in the Oppenheimer household, the decisions that I made about the upbringing of Little Ricky Ricardo would be seen and judged by tens of millions of people every week.

As the minutes ticked by, my thoughts reached back to my own childhood in San Francisco, a chapter in my life that had laid the first solid brick on the road to

I Love Lucy.

Of one thing I was sure—the childhood that I would write for Little Ricky would be very different from mine.

IT WAS THE SUMMER OF 1948. My wife, Es, was eight months pregnant. We had just bought a new house. And for the first tim in years, I was out of work. I was sitting in my office one hot afternoon in August, wondering what to do next, when the telephone rang.

It was Harry Ackerman, head of West Coast network programming for CBS Radio. “Jess,” he began, “have you heard the new show Lucille Ball is doing for us—

My Favorite Husband?

”

I told him I hadn’t heard it.

“Well it’s only been on for a few weeks.

Fox and Davenport have been doing most of the writing, but they’ve got to go back to

Ozzie and Harriet

when the hiatus is over. Would you be interested in writing a script for us?”

Well, in the previous twelve years I had worked with practically every star in Hollywood, but for some reason I had never run into Lucille Ball.

I knew who she was, of course—I had seen her in

Stage Door,

with Katharine Hepburn, and

The Big Street,

with Henry Fonda. But apart from that I

knew relatively

little about her. The impression I had of her was that of a wisecracking showgirl type—a far cry from the Baby Snooks character I had been writing for the past five years. But Harry had caught me in a receptive mood.