I Love You, Ronnie (13 page)

RONALD REAGAN

Dec. 25–1975

Dear Mommie

The Star in the East was a miracle as was the Virgin Birth. I have no trouble believing in those miracles because a miracle happened to me and it’s still happening.

Into my life came one tiny “dear” and “a light shone round about.”

That light still shines and will as long as I have you. Please be careful when you cross the street. Don’t climb on any ladders.Wear your rubbers when it rains. I love my light and don’t want to be ever in the dark again.

I love you—Merry Christmas—

Your ranch hand.

On the deck at the San Onofre house.

W

e remained private citizens only briefly. Everyone but me, it seemed, simply took it for granted that Ronnie would run for president in 1976. He was willing—and I was certainly willing to support him, as always. And so before I knew it, we were back on the campaign trail, only this time Ronnie was expressing his views to a national audience. Ron traveled with us for a time, setting up microphones before campaign events as part of a school project. Maureen, especially, was delighted—she’s a real political junkie. She played an active role in the campaign and was often by our side. Michael was there when he could be.

You might think that Ronnie’s decision to run for president was a big turning point for our family or for us as a couple. While it was in certain ways, in others it wasn’t. We didn’t agonize over whether or not Ronnie should run. Quickly enough, it just became obvious that running for president was what Ronnie was going to do and that I was going to support him. If Ronnie was worried after he made his decision, he never let on. If I sometimes knew he was worried, it wasn’t because he told me; it was just because I knew him so well. I never heard him express real fear or self-doubt; I don’t think he really felt either.As I’ve said before, he liked a good competition. In any case, we didn’t worry about the consequences once he’d made his decision. We weren’t ones for family meetings—we just gradually came to a resolution.

In those days, running for president was completely different from what it’s like today. There weren’t the huge amounts of money you read about candidates spending now. We always had a lot of volunteers, lots of young people, and we really depended on them. We had a plane that we called the Yellow Banana, and we stayed in little nothing motels, real fleabag places sometimes. We spent little on food—Mike Deaver would often go out and get us Kentucky Fried Chicken for dinner. Once, I remember, in the South, we campaigned all day in the pouring rain. The rain ran up into our sleeves as we stood and waved. When we got back to our motel, soaked and frozen through, the manager refused to turn on the heat. So we finally had to leave, with all our staff and our baggage, and find another hotel room, with heat. That, for us, was a luxury.

The contact with the public was wonderful. However, we were losing every state. Everyone kept saying to Ronnie, “I think we’re going to have to get out,” but Ronnie just said, “No, I’m in it to the end.” Then came North Carolina, and we won. And from then on Ronnie won every state.

The 1976 Republican convention in Kansas City was exciting. It was, in fact, the most exciting convention I’ve ever been involved with. For the nominating process, Jerry Ford’s people put us way in the back of the hall, where no one could really see us. And yet when we went into our box on the last night, the people just wouldn’t let Ronnie sit down. They kept yelling, “Speech! Speech!” Ronnie tried at one point to speak, but they drowned him out; there was no way he could be heard. Frank Reynolds, the ABC newsman, came to the box to interview Ronnie, but it was impossible, and I heard him say, “This may not be the best journalistic derring-do, but I think I’ll let him have this time.”

The delegates’ final vote was close, but we had known fromthe procedural vote the night before that President Ford would win the nomination. Now, after the final tally, Ford invited us onstage, and when we stood up front with the Fords, Nelson Rockefeller, and others, the response was amazing. The auditorium was packed. So many people were standing there, tears streaming down their faces, absolutely silent, waiting for Ronnie to speak. You could have heard a pin drop.

As we stood there, Ronnie whispered to me: “I don’t know what to say.”

I thought, Good Lord. I hope he thinks of something.

And then he gave the most wonderful speech. He talked about how he’d been asked to write a letter for a time capsule to be opened in Los Angeles for the tricentennial, a hundred years later. It was a call for unity and victory, and for the political will to strengthen our country, protect our freedoms, and save the world from the threat of nuclear destruction. The crowd shouted and clapped—it seemed they would never stop clapping.

The next morning, Ronnie met with a group of young volunteers. He quoted from one of his favorite poems, an old English ballad he had learned in school: “I will lay me down and bleed a while / Though I am wounded, I am not slain. / I shall rise and fight again.” At a later meeting, which I also attended, he said:

The cause goes on. It’s just one battle in a long war and it will go on as long as we all live. Nancy and I, we aren’t going to go back and sit in a rocking chair on the front porch and say, That’s all for us.

You just stay in there, and you stay there with the same beliefs and the same faith that make you do what you’re doing here. The individuals on the stage may change. The cause is there, and the cause will prevail, because it is right.

Don’t give up your ideals. Don’t compromise. Don’t turn to expediency. And don’t, for heaven’s sake, having seen the inner workings of the watch, don’t get cynical.

No, don’t get cynical. Don’t get cynical, because look at yourselves and what you were willing to do, and recognize that there are millions and millions of Americans out there who want what you want, who want it to be that way, who want it to be a shining city on a hill.

I was crying, and a lot of other people in the room were, too.

I think there really was no doubt in anyone’s mind that in 1980 Ronnie would win the nomination. It seemed preordained, really, after the 1976 campaign. He was ready, and everything seemed to fall into place. I remember his winning line in the debates: “There you go again,” he’d say to Jimmy Carter every time President Carter started talking about the nation’s “malaise.” Everyone knew it was over after that. Ronnie had won the debate—and he would carry the election.

The country was ready for him. People were eager for someone to paint a positive, optimistic picture of the country. Ronnie made them believe that we had a bright future. He made people feel good about themselves and good about the country. And, quite simply, they liked him.

—

We traveled constantly during the campaigns, and often enough, we traveled apart. After our years of always being together, this was hard to get used to. As Ronnie wrote, in this lovely Valentine’s letter just after the 1976 campaign, all we both ever really wanted was to be in the same room.

RONALD REAGAN

Feb. 14, 1977

Dear St.Valentine

I’m writing to you about a beautiful young lady who has been in

this household for 25 years now—come March 4

th

.

I have a request to make of you but before doing so feel you should know more about her. For one thing she has 2 hearts—her own and mine. I’m not complaining. I gave her mine willingly and like it right where it is. Her name is Nancy but for some time now I’ve called her Mommie and don’t believe I could change.

My request of you is—could you on this day whisper in her ear that someone loves her very much and more and more each day? Also tell her, this “someone” would run down like a dollar clock without her so she must always stay where she is.

Then tell her if she wants to know who that “someone” is to just turn her head to the left. I’ll be across the room waiting to see if you told

her. If you’ll do this for me, I’ll be very happy knowing that she knows I love her with all my heart.

Thank you,

“Someone”

If either of us ever left that room, we both felt lonely. People don’t always believe this, but it’s true. Filling the loneliness, completing each other—that’s what it still meant to us to be husband and wife. Ronnie put it like this one Christmas:

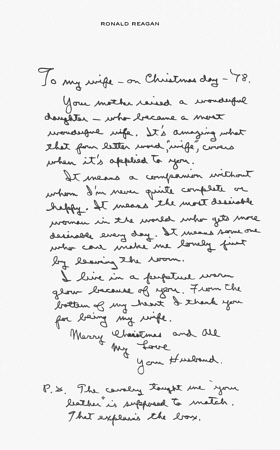

RONALD REAGAN

To my wife—on Christmas day—’78.

Your mother raised a wonderful daughter—who became a most wonderful wife. It’s amazing what that four letter word,“wife”, covers when it’s applied to you.

Ronnie’s 1978 Christmas letter and Christmas-tree doodle.

It means a companion without whom I’m never quite complete or happy. It means the most desirable woman in the world who gets more desirable every day. It means some one who can make me lonely just by leaving the room.

I live in a perpetual warm glow because of you. From the bottom of my heart I thank you for being my wife.

Merry Christmas and All My Love,

Your Husband.

P.S. The cavalry taught me “your leather” is supposed to match. That explains the box.

By the time of Ronnie’s second presidential campaign, in 1980, we were a bit more used to traveling apart. We accepted it—there was a lot of terrain to cover. But that didn’t mean we liked it.

(Thirty-three was Ronnie’s lucky number. It had been his football number in college.)

Hey little Mommie—how come it keeps getting harder to say good-bye?

You’d think I’d be used to it but I’m not. I’m NOT REPEAT NOT going to get that way.

Maybe that job in Wash. wouldn’t be so bad—you’d be right upstairs.

I love you very much and miss you very much and I haven’t even left home.

Don’t talk to strangers—or open the door—just lock yourself in the closet and I’ll let you out tomorrow afternoon.

I love you—(Special Agent) 33

That year, we even woke up apart on our anniversary.

RONALD REAGAN

March 4

th

[1980]

Good morning Honey. Isn’t this an awful way to start an anniversary? I’m where I don’t want to be and you’re where (I hope) you wish I could be. And where I will be soon—the Lord and an airline willing.