I Love You, Ronnie (8 page)

Ronnie played Commander Casey Abbott. I was a navy nurse. He went down to San Diego to start shooting before I was called in. Then, when I showed up for my first day of work, I found this note waiting in our hotel room:

THE U.S. GRANT

Darling

Us old “Salts” always say “Welcome Aboard.”—And My Goodness

AreYou Welcome!?!

We are working a while tonite so come on out to the war when you have “stowed your gear” (Heave Ho)

I love you

Commander Abbott

I loved working with Ronnie. Anytime I could be with him, I loved it. All went fine on the set—until, toward the end of the film, brave Commander Abbott had to take his leave and said good-bye to me. I began to cry—really cry. I guess there had been too many real-life good-byes in those days.

The director shouted “Cut!” and the scene had to be reshot.

The truth was, though, it was hard for both of us to say good-bye.

And as the G.E. years lengthened, it became particularly hard for Ronnie to spend long periods of time away from home and the family.

A letter that was waiting for me in our hotel room when I joined Ronnie to make

Hellcats of the00 Navy,

the only picture we made together.

His telegrams now became more and more filled with longing.

WHAT AM I DOING HERE WHEN I WANT TO BE THERE. I MISS YOU & LOVE YOU.

WHY IS IT I DON’T GET AROUND TO SPEAKING MY MIND MORE OFTEN LIKE HOW MUCH I LOVE YOU AND HOW LOST I’D BE WITHOUT YOU.

HOW COME IT DOESN’T GET ANY EASIER. I MISS YOU VERY MUCH PROBABLY BECAUSE I LOVE YOU VERY MUCH.

As Ronnie traveled around the country for

General Electric Theater,

visiting plants and meeting with executives, he learned what was on people’s minds. He heard people complain about the bigness of government and the burden of high taxes. The government, they said, was taking too much away from them. Ronnie knew what they meant. When we were first married, 90 percent of his salary had gone to the government. It got to the point where he had to turn down pictures because there was just no financial reason to make them.

Hearing other people’s stories, hearing what bothered them and what they wanted, was a wonderful opportunity for Ronnie. He toured every single G.E. plant, walking miles and miles, talking and shaking hands with the plant workers. Afterward, he’d come home and tell me about meeting those people and how important it was to him.

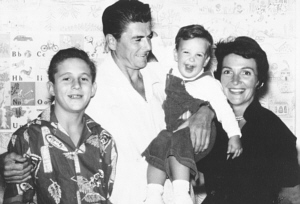

A family Christmas photo, from when Ronnie was working for G.E.

Soon, Ronnie’s speeches became shorter and shorter, and his Q & A sessions longer and longer. People didn’t ask him about toasters, and gradually, his talks became more political. He learned a lot by listening to the hundreds of people he saw and hearing what was on their minds and what was worrying them. He began to express his concern that excessive government regulation was draining the American economy and the free-enterprise spirit, which is what he was hearing. His political views were changing. He’d gone into the G.E. years a Roosevelt Democrat—and he’d remained a Democrat even while petitioning Dwight Eisenhower to run for president and campaigning for Richard Nixon. But with time, his political views had shifted more dramatically. And a new set of views formed that would eventually lead him to the governorship of California and then to the presidency.

Interestingly, General Electric never told Ronnie what to say or asked him to tone down the political content of his speeches until shortly before his show went off the air, under ratings pressure from the new color show,

Bonanza,

in the spring of 1962.And then, when G.E. told him to stop talking politics and start talking product, Ronnie simply refused. “I can’t do it,” he said. “When people ask me to speak, I can’t switch lines completely and talk about appliances.” He knew that when people went to see him, they wanted to hear what he thought—and to get the big picture.

With Mike, when he was living with us in the San Onofre house.

Ronnie and Ron, summer 1962.

W

hen the travel for G.E. came to an end, we had a few years, from 1962 to 1965, of relative calm. Ronnie taped a couple of television episodes—for

Wagon Train

and

Kraft Suspense Theatre—

then spent a season as host of

Death Valley Days.

He was at home in those years much more than he’d ever been before in our married life, and he was glad to have a full-time family life.

When he wrote this letter, in May 1963, he was in New York, working in television and collaborating with the coauthor of his early autobiography,

Where’s the Rest of Me?

What was clearly in the forefront of his mind, however, was a troubling conversation we’d had the night before about the children.

Mike, who had come to live with us in 1959, when he was fourteen, was making some steps toward independence. Ronnie wanted to support and guide him but also felt that he, like all our children, needed the space to sometimes make his own mistakes. He was away so much that disciplining the children usually fell to me—as it often does to women whose husbands travel a lot. But the children always knew that he was there for them, and he always made his principles and beliefs very clear. In fact, years later, when Patti went to college at Northwestern and wanted to live in a coed dorm, it was Ronnie who surprised her by saying no. “I never expected to hear that from you,” she said. “From Mom maybe, but not from you.”

The Skipper was what we called Ron. He was such an easygoing child that we also called him Happy Jack.

RONALD REAGAN

PACIFIC PALISADES

Thurs. [May 24, 1963]

My Darling

Last night we had our double telephone call and all day (I didn’t work) I’ve been re-writing the story of my life as done by Richard Hubler. Tomorrow I’ll do my last day of location and then I’ll call you and I’ll tell you I love you and I’ll mean it but somehow because of the inhibitions we all have I won’t feel that I’ve expressed all that you really mean to me.

Whether Mike helps buy his first car or spends the money on sports coats isn’t really important. We both want to get him started on a road that will lead to his being able to provide for himself. In x number of years we’ll face the same problem with The Skipper and somehow we’ll probably find right answers. (Patti is another kind of problem and we’ll do all we can to make that one right, too.) But what is really important is that having fulfilled our responsibilities to our offspring we

haven’t been careless with the treasure that is ours—namely what we are to each other.

Do you know that when you sleep you curl your fists up under your chin and many mornings when it is barely dawn I lie facing you and looking at you until finally I have to touch you ever so lightly so you won’t wake up—but touch you I must or I’ll burst?

Just think: I’ve discovered I can be fond of Ann Blyth because she and her Dr. seem to have something of what we have. Of course it can’t really be as wonderful for them because she isn’t you but still it helps to know there are others who might just possibly know a little about what it’s like to love someone so much that it seems as if I have my hand stretched clear across the mountains and desert until it’s holding your hand there in our room in front of the fireplace.

Ronnie reading to the children, at the San Onofre house, at Christmas.

Probably this letter will reach you only a few hours before I arrive myself, but not really because right now as I try to say what is in my heart I think my thoughts must be reaching you without waiting for paper and ink and stamps and such. If I ache, it’s because we are apart and yet that can’t be because you are inside and a part of me, so we aren’t really apart at all. Yet I ache but wouldn’t be without the ache, because that would mean being without you and that I can’t be because I love you.

Your Husband

Ronnie wasn’t, of course, going to stay a private citizen for long. He had joined the Republican party in 1962. By the mid-1960s, he was an influential party voice, repeatedly asked by local leaders to campaign for their candidates.

In 1964, he was asked by Holmes Tuttle, a successful Ford dealer in Los Angeles, to make a fund-raising speech on behalf of Barry Goldwater at the Ambassador Hotel. That speech, which Ronnie wrote himself, went over so well that afterward, Holmes raised the money to have it televised and Ronnie’s words attracted national attention. “You and I have a rendezvous with destiny,” he said. “We can preserve for our children this, the last best hope of man on earth, or we can sentence them to take the first step into a thousand years of darkness. If we fail, at least we can let our children, and our children’s children, say of us we justified our brief moment here. We did all that could be done.” The televised speech brought in $8 million—more than had ever been raised for a candidate before.