I Love You, Ronnie (4 page)

I remember the morning of our wedding day so well. At my apartment in Westwood, I got dressed in the wedding suit that I’d chosen at I. Magnin’s: a gray wool suit with a white collar, which I wore with a small flowered hat with a veil. Frieda was there with me, and just before Ronnie came to pick me up for the ceremony, we called my mother. “Oh, Mrs. Davis,” Frieda said when she got on the phone. “You should see her—she’s so happy!”

It was true. I was very, very happy, and everyone seemed to be happy for us.

Ronnie arrived soon afterward with my wedding bouquet, and we drove to the church together. I was in the clouds as we walked into the church. In fact, I was so far off in the stratosphere that I didn’t even notice that Ardis Holden was sitting on one side of the church and Bill was on the other. They’d had a terrible fight—but for me, none of it registered. I was in a happy fog, and I also managed not to hear much of the wedding ceremony. I missed it altogether when the minister said what I most wanted to hear: “I now pronounce you man and wife.” I only came to when Bill Holden leaned over and said, “Let me be the first to kiss the bride.”

“No, Bill,” I said. “He hasn’t married us yet.”

Bill laughed and said, “Nancy, he has. It’s all done.”

Isn’t it funny—it’s always been like that for me: At very emotional moments in my life, it’s as if I’m in a daze. For instance, I have almost no recollection of Ronnie’s first inauguration. Now, when I watch tapes of the event, I think: I wish I could live that all over again.

After the wedding ceremony, we went back to Ardis and Bill’s house and immediately called my parents and Nelle. We also called Michael and Maureen at Chadwick. The Holdens had wanted to give a party for us, and we’d said no. But they did have a photographer there, thank goodness—if they hadn’t insisted, we wouldn’t have any wedding pictures today. I, of course, still didn’t know that they’d had this terrible fight and were not speaking to each other. We had dinner, a cake, and a champagne toast by Bill, and then Ronnie and I went to Riverside and spent our wedding night at the Old Mission Inn. I remember that Ronnie carried me over the threshold and that there were red roses waiting for me in the room. We stayed just one night at the hotel, and the next morning we left for Phoenix, to spend our very short honeymoon at the Arizona Biltmore with my family. Before we left, we gave my red roses to an elderly woman, who was sick and staying in the room across the hall from ours.

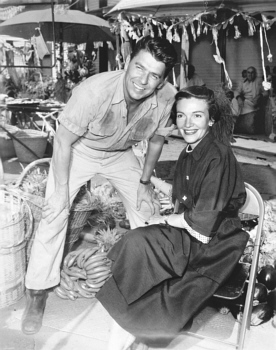

Visiting Ronnie on the set; with his mother, Nelle, and my parents, 1953.

On the road to Phoenix there were animal stands, where you could go in and see snakes and other local wildlife, mostly snakes. Terribly romantic—and we had to stop at every one! I wasn’t mad for that part of the trip. These places were tiny, and when you went inside, you had to walk down a narrow passageway with snakes on either side. They smelled just awful. But Ronnie wanted to see the snakes, and he thought I should become familiar with them, because we were going to have a ranch.

After just a few days in Phoenix, we started back for Los Angeles, where Ronnie had a picture commitment. On the way home, there were high winds and they split the top of Ronnie’s convertible. So the honeymoon ended with me on my knees in the front seat of the car holding down the top. We had to stop every once in a while so I could warm my hands.

Later on, quite a bit later on, I learned a funny thing about our wedding day. After all our precautions about keeping our wedding date and location a secret, Tommy, one of the captains at Chasen’s, said to us: “You know, I knew when and where you were going to be married.” He’d overheard us talking at dinner, and he’d been there across the street from the church, watching. We never knew, and he never said a word to anyone. He’d just wanted to be near us. We found this kind of kindness toward us on the part of many people, over and over again in the different phases of our life together.

A month after we were married,

I visited Ronnie on the set.

W

hen we first returned from Phoenix, we had two separate apartments—we hadn’t yet had time to find a house to live in together. We lived at my place and Ronnie kept some of his clothes at his, and for a while he ran back and forth for suits and ties. Soon, however, we found our first home together—a single-level three-bedroom house in Pacific Palisades, which in those days was considered way out in the country. We paid $42,000 for it. Imagine what it’s worth today! Every once in a while, I drive by to see it and the olive tree Ronnie planted in the front to be there when I came home from the hospital after having Patti.

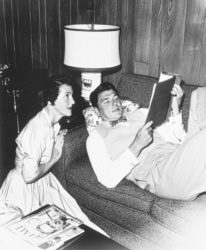

I loved that house. It was the first house that I’d ever lived in. It had a library, a small study that we made for Ronnie out of one of the bedrooms, and a wonderful garden, where Patti liked to play in her sandbox. As she grew, she spent hours outside in that garden, sliding down her slide and playing in her sandbox. We had an English nanny, who loved to play the horses, and she and Ronnie had long conversations about the horse races. We went to the ranch often, saw friends, and had small dinner parties, but mostly we spent our time at home together on the weekends, doing things around the house, watching TV, and eating popcorn, as we always had. A big neighborhood dog adopted us for a while, and I remember how she’d come over and watch TV with us too, sitting stretched out in a comfortable chair.

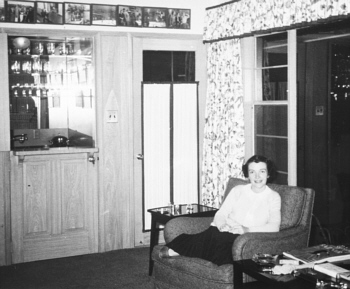

From the scrapbook we made in the 1950s. Ronnie wrote “our 1

st

home” under this snapshot of me in the library of the house on Amalfi; November 1952.

Our first years of marriage were not easy, though. Things were not going well for Ronnie in pictures. Hollywood had moved away from his style and image into a different feeling, which seemed to me darker and moodier. His career was really going downhill. He’d be sent scripts that were just awful, and he did a couple of pictures that were just awful.

We couldn’t afford to furnish our living room. For special occasions, we’d reward ourselves by working on our house or garden—we’d paint a room, for instance. It was very, very hard for Ronnie. Yet it wasn’t so different from what other young families getting started go through, and I had what I had always wanted: a husband I loved, and a family.

At home in the 1950s, in the house on Amalfi Drive.

I had stopped working when Patti was born. Ronnie didn’t ask me to—he would never have asked me to give up my career. It was my idea. I liked acting, but I had seen too many two-career Hollywood marriages fail. Ronnie was my whole life. I couldn’t imagine life without him, and I didn’t want to run the risk of anything happening to us. Also, I had seen my mother build a really happy marriage, putting a fine career as an actress aside.

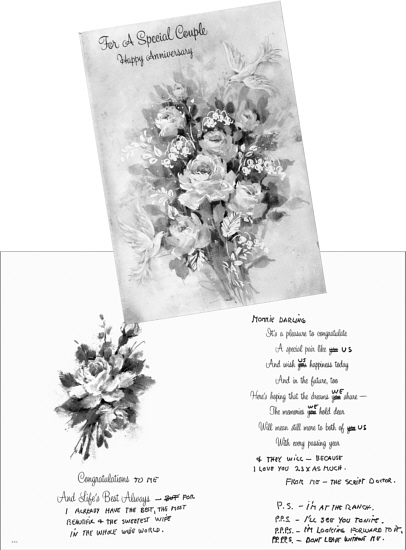

Anniversary card.

When I left MGM, I had eight films behind me. I was proud of what I’d accomplished, and happy to stop there. I wanted to be a wife and mother. When we hit a dry spell financially, however, I felt I needed to go back to work, at least temporarily. I took a part in a film called

Donovan’s Brain,

a science-fiction picture in which Lew Ayres plays a scientist who tries to keep a brain alive and is taken over by it. I see it often on TV now.

Ronnie came to visit me on the set of

Donovan’s Brain.

Ronnie made low-budget movies, accepted some TV parts, and even did a short stint as a Las Vegas nightclub host. His letters in this period were filled with wonderful descriptions of the places he was going and the people he was seeing. I found them so beautiful that I read them over and over again, even though they made me miss Ronnie so much.

This one—a real favorite—makes me weepy every time I read it.

THE SHERRY-NETHERLAND

NEW YORK, N.Y.

Wed. July 15 [1953]

Dear Nancy Pants

Yesterday I went directly from the train to rehearsal—only stopping to check in here. Then suddenly it was two p.m. and rehearsal was over.

Back at the hotel I put in the call to you and then tried for Lew Wasserman—not in town! Sonny Werblin—away on vacation! Nancy Poo Pants Reagan—away out yonder! Eight million people in this pigeon crap encrusted metropolis and suddenly I realized I was alone with my thoughts and they smelled sulphurous.