I Love You, Ronnie (18 page)

We got him on a plane and immediately took him to a hospital in Tucson, Arizona. He should really have stayed there, but it was my birthday and the Wilsons had planned a celebration, and Ronnie was determined to go back to the ranch. We went back—but at my insistence, we took a doctor with us.

The day after my birthday, we flew home. I was very uneasy and kept at Ronnie until he agreed to get his head X-rayed. We went to the Mayo Clinic, where we’d gone every year for our checkups. It turned out that Ronnie had a concussion and a subdural hematoma. He needed to be operated on right away. It all happened so quickly that I think, once again, I was in shock. It shows up in the picture that appeared in the press at the time: Ronnie leaving the hospital, taking his hat off to salute the crowd, and me dashing forward trying to cover his partially shaven head with my hand. He didn’t care that he had no hair on one side—but I did!

I’ve always had the feeling that the severe blow to his head in 1989 hastened the onset of Ronnie’s Alzheimer’s. The doctors think so, too. In the years leading up to the diagnosis of the disease, in August 1994, he had not shown symptoms of the illness. I didn’t suspect that Ronnie was ill when we went back to the Mayo Clinic that summer for our regular checkup. When the doctors told us they’d found symptoms of Alzheimer’s, I was dumbfounded. Ronnie’s fall from the horse had worried me terribly, of course, and I’d had to urge him to take time out to recover after his operation. But I had seen no signs of anything else.

I also didn’t realize at the time what an Alzheimer’s diagnosis really meant. It’s a disease that people are still not terribly knowledgeable about, and a few years ago, they were even less so. Families treated it like a dark secret, so people—the patients and their families—suffered in isolation. It’s only recently that people have started to speak out and to treat it as a disease like any other.

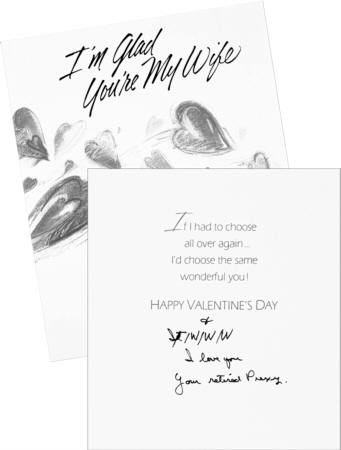

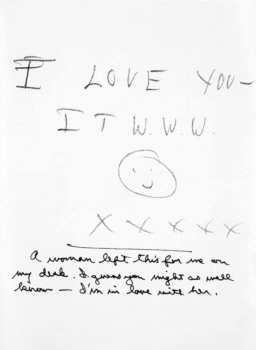

A Valentine from “your retired Prexy,” 1990.

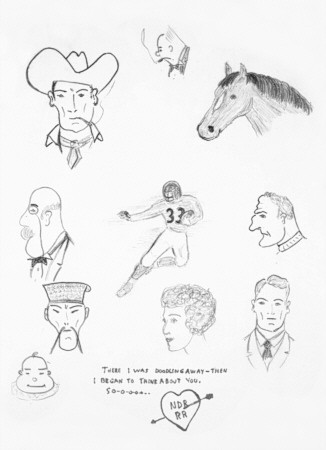

Another doodle that I love. I had this one framed, too, and keep it on my desk.

The diagnosis didn’t sink in for a while. Neither one of us really knew what was going to happen, but of course we knew it wasn’t good. Ronnie reacted the way he always has with everything—he just went ahead and dealt with it. Like most people then, I didn’t know much about Alzheimer’s (looking back, I suppose this was just as well), but I was certainly going to learn! I got the book

The 36-Hour Day,

which is given to caregivers, and sent one to each of the children so that they could learn more about the disease, too.

I have often in recent years recalled a conversation Ronnie had with Cardinal Cooke shortly after the shooting in 1981. “God was certainly sitting on your shoulder that day,” the cardinal said. Ronnie replied, “Yes, I know, and whatever days are left to me, they belong to Him.”

Once in a while I would wonder whether that conversation played a part in Ronnie’s decision to write his beautiful letter to the American people about his Alzheimer’s. After the shooting, both of us always went public with our health problems when we were in the White House. We believed strongly that it helped people—and it did. When Ronnie talked about his colon cancer, more people went to be tested. When I talked about my breast cancer, more women had mammograms. So when we heard this diagnosis, Ronnie once again thought about ways that his own experience could help other people. And I do think that writing the letter served the purpose he hoped for: More people now understand that Alzheimer’s is a disease like any other and not a reason to be embarrassed or self-conscious, and research has increased.

Ronnie wrote the Alzheimer’s letter at a table in the library and gave it to me to read before it was released. I was surprised when people later asked who had drafted the letter, because it seemed so clear to me that they were his words, that it was his natural way of writing.

It is difficult to describe my life now. People are incredibly kind and sympathetic—in an elevator, on the street, everywhere. And the mail, which is tremendous, reflects the same concerns and feelings. I can’t begin to say how much this means to me and how helpful it is. First of all, there is a feeling of loneliness when you’re in this situation. Not that your friends aren’t supportive of you; they are. But no one can really know what it’s like unless they’ve traveled this path—and there are many right now traveling the same path I am. You know that it’s a progressive disease and that there’s no place to go but down, no light at the end of the tunnel. You get tired and frustrated, because you have no control and you feel helpless. We’ve had an extraordinary life, and I’ve been blessed to have been married for almost fifty years to a man I deeply love—but the other side of the coin is that it makes it harder. There are so many memories that I can no longer share, which makes it very difficult. When it comes right down to it, you’re in it alone. Each day is different, and you get up, put one foot in front of the other, and go—and love; just love.

I try to remember Ronnie telling me so many times that God has a plan for us which we don’t understand now but one day will, or my mother saying that you play the hand that’s dealt you. It’s hard, but even now there are moments Ronnie has given me that I wouldn’t trade for anything. Alzheimer’s is a truly long, long good-bye. But it’s the living out of love.

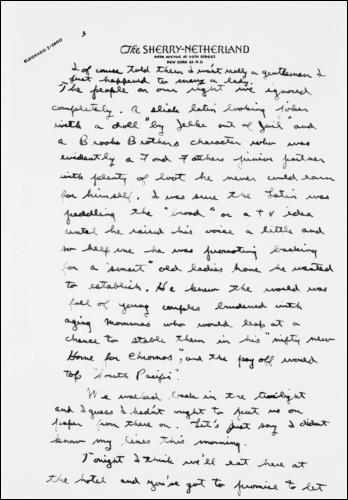

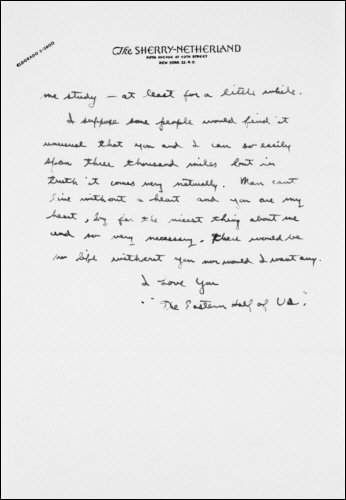

A note I left for Ronnie—and his reply.

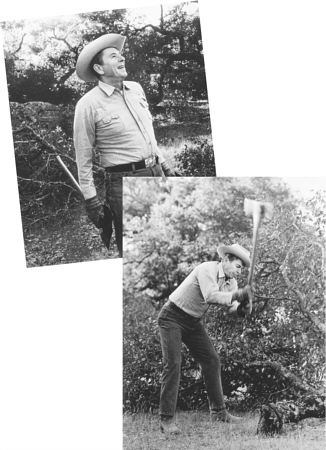

THIS PAGE AND TOP RIGHT:

Ronnie working outdoors at Rancho del Cielo.

Riding at Rancho del Cielo.

November 5, 1994

My Fellow Americans,

I have recently been told that I am one of the millions of Americans who will be afflicted with Alzheimer’s Disease.

Upon learning this news, Nancy & I had to decide whether as private citizens we would keep this a private matter or whether we would make this news known in a public way.

In the past Nancy suffered from breast cancer and I had my cancer surgeries. We found through our open disclosures we were able to raise public awareness. We were happy that as a result many more people underwent testing.

They were treated in early stages and able to return to normal, healthy lives.

So now, we feel it is important to share it with you. In opening our hearts, we hope this might promote greater awareness of this condition. Perhaps it will encourage a clearer understanding of the individuals and families who are affected by it.

At the moment I feel just fine. I intend to live the remainder of the years God gives me on this earth doing the things I have always done. I will continue to share life’s journey with my beloved Nancy and my family. I plan to enjoy the great outdoors and stay in touch with my friends and supporters.

Unfortunately, as Alzheimer’s Disease progresses, the family often

bears a heavy burden. I only wish there was some way I could spare Nancy from this painful experience. When the time comes I am confident that with your help she will face it with faith and courage.

In closing let me thank you, the American people, for giving me the great honor of allowing me to serve as your President. When the Lord calls me home, whenever that may be, I will leave with the greatest love for this country of ours and eternal optimism for its future.

I now begin the journey that will lead me into the sunset of my life.

I know that for America there will always be a bright dawn ahead.

Thank you my friends. May God always bless you.

Sincerely,

Ronald Reagan

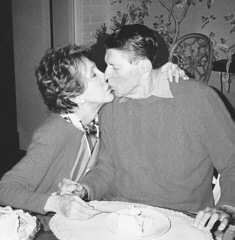

Kissing Ronnie “Happy Birthday,”

February 6, 2000.

PHOTO CREDITS

Courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Library:

Gabi Rona, courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Library: jacket,

Courtesy of the University of Southern California, on behalf of the USC Library Department of Special Collections:

Author’s collection:

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Look Magazine Photograph Collection:

© 1978 John Engstead/MPTV:

Courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation: