IGMS Issue 11 (13 page)

Authors: IGMS

Stars were filling the sky. All the houses were lit up inside, all the streetlights on. Mother would be angry with me. She'd have sharp words with me while she slathered us with Calamine lotion. But Karin wasn't ready to go back.

"What are you going to do with that stuff?" I said, nodding at the basket in her lap.

She hugged the basket to her chest. "What do you think I should do?"

"Pour it all out and throw the bottles away. We'll burn the basket until there's nothing left but ashes."

"Perhaps that would be best, if you think so," she said.

"I think we should get the law. We should tell the sheriff."

Karin shook her head. "You don't understand." Her shoulders were tight. She took deep breaths.

"Oh, my poor Elena," she said at last. "Tell me who is it that makes justice here."

"What do you mean?"

"Who decides which people are to be arrested?" she said patiently. "Think now."

I did think. And slowly I realized that Marshburn, Foust, and Roberson would never be arrested, never go to jail, never stand trial. My throat squeezed up and my head throbbed. Marshburn was the Sheriff's cousin. Foust was on the town council. Roberson played cards with everybody.

"The law is the law," I said feebly. "And if it isn't . . . then it ought to be."

"I agree," she said.

I never knew what she did with the basket or its contents. I never saw it again. We told no one about the murder. We never spoke about these things or that day again.

Foust, Roberson, and Marshburn wandered into town five days later. They were naked, dirty, and pretty banged up. Folks assumed they'd got hold of a bad batch of moonshine and it had messed them up so that they didn't know where they were. After Doctor Fred patched them up, they looked like their regular selves.

But those men had changed. An indelible, unmistakable cast of confusion remained on their faces, and everyone noticed that after they returned, they rarely looked folks in the eye. Karin dutifully recorded these events in her notebook without comment.

She finished high school two years ahead of me and left LaGrange for Mount Holyoke College. I'd known for some time that she did not intend to return. She had inherited a great deal of money, which made it possible for her to pursue her studies without pause. But she kept in touch with us over the years as she bounced from one university to another, gathering post-graduate degrees like daisies.

My early letters were filled with gossip about the home folks she'd known. When I wrote that I had decided to study law, she responded with a postcard. It had but one word on it: "Brava!"

In time, her letters came less frequently, and I answered them after months rather than weeks. By the time I was admitted to the bar, our correspondence had stopped altogether. Her phone call on Christmas Eve 1971 was the last. She seemed content with her life. But she sounded as driven as ever. It was an awkward conversation and we ended it with a hasty exchange of pleasantries.

My occasional attempts to reconnect went unanswered. She lived in her lab. But then, what did we really have to talk about? It was enough for both of us to know that the other was alive and in pursuit of her own happiness.

I was a young widow with two teenage boys when I was appointed to the bench. After nearly four decades as a state court of appeals judge, I was looking forward to a long, pleasant retirement spent playing with my grandchildren and digging in my garden. But those joys didn't wear well for me. I suppose, in retrospect, I was as driven as ever Karin was.

I accepted an urgent request from the United Nations to join the World Court. I was assigned to the 12

th

Tribunal in Kampala, Uganda. The speed with which these events occurred was dizzying. The Court was soon forced to hold round-the-clock hearings to accommodate the rapidly growing numbers of desperate people who were surrendering to UN authorities. The vast majority of them insisting they were guilty of "crimes against humanity."

A few of these self-confessed criminals were so old that their names and crimes had been long forgotten and most evidence and documentation buried among the dust-covered boxes of moldering files in storerooms at The Hague.

In Kampala, I presided over the trials of frightened, wretched men -- many with bony growths on their misshapen, ulcer-ridden heads, and thick, leathery tails packed uncomfortably into their trousers. And others who were terrified that they too would succumb to the same mysterious and untreatable affliction.

I dropped Karin a post-card the other day. It had but one word on it: "Brava!"

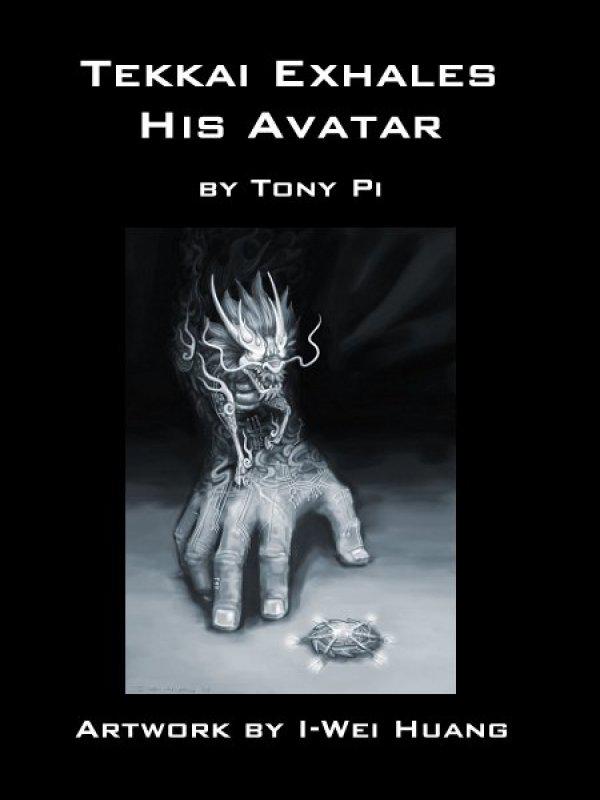

by Tony Pi

Artwork by I-Wei Huang

Well into the ninth year of Tekkai's incarceration, Kagami Maeda came again to tempt him. Twice before, the World Priority officer had asked him to inform on his old comrades. Twice he had refused her. He blamed her still for robbing him of freedom, for tearing him from the electric ecstasies of the Floating Worlds.

Yet Maeda had promised to show him what his boy looked liked now in his teens, if he but listened. With nine lost years and twenty to go, Tekkai feared the gnaw of years on the memories of his son. At last, he mulled Maeda's offer.

The guard shoved Tekkai into a musty interrogation room, a stark affair in cracked cement with a two-way mirror giving the cramped chamber the illusion of greater width. Kagami Maeda sat poised behind a desk of aged wood, the crest of the Priority on her grey suit iridescent under the flickering light. The thin, angular woman's neuro-rosette glinted like a silver third eye between her eyebrows.

Having only seen crystalline models before, Tekkai studied Maeda's metallic rosette. The reflective 'eye' transfixed him with its seeming gaze. He knew well that the device did not see,

per se

; it simply tapped into the user's five senses and fed the data into the mimicstreams. Still, the mere idea that the eye was staring through his flesh made his hackles rise.

"Leave us," Maeda said to the guard. Then she looked at Tekkai and gestured at the rickety stool across from her. "Prison has not been kind to you, Ryo Takahashi. Please, sit."

He straddled the seat and slammed his calloused hands on the table. "Call me Tekkai." It was his Immortal name, his hacker's handle, although that archaic term was far from accurate. In the world of the mims, virtuosos like him styled themselves after bandit kings and gods, twisting the system to sate their pride and greed. Tekkai's vice was his affection for the forbidden art of viruses, for which he had a divine talent. But twelve years ago, when a data-theft uncovered the true atrocities behind the rise of the new world government, the honorable among them vowed to bring down the Priority together, and thus were the Immortals born. "What will you have me do, and what will it cost me?"

"Nothing but a friendship already dead, Tekkai," Maeda said. "Find Gama in the Floating Worlds and trace his physical coordinates. That's all we ask."

Tekkai's hands clenched.

Gama

was the third of seven names in his nightly mantra, one of the Immortals who might have betrayed him nearly a decade ago, sending in the tip that took him from his son. If he could corner Gama, he might force the truth from him. "Why me? I haven't immersed in the mimicstreams in years. Surely advances in that technology have long outstripped my skills. What can't your cadres of Priority agents handle better?

"Your code was the basis for many of the Immortal tricks, was it not?" Maeda asked.

"Allegedly." Tekkai thumbed the spot of bare skin between his knitted eyebrows.

"Even our best cryptographers couldn't break your

sennin

encryption. Besides, who would know Gama and his tricks better than a fellow Immortal?"

Tekkai could not argue with her logic. He rubbed the

ki-rin

tattoo on his forearm. "What's Gama done, aside from the usual felonies, I mean?"

"Does it matter?" Maeda thrust a fist before him and revealed what she hid in her palm: a hexagonal neuro-rosette with fern-like dendrites in a familiar pattern. "Taste Immortality again, Tekkai." She set the rosette on the tabletop within easy grasp.

The crystal was his personal design, of that there was no doubt, state-of-the-art before his arrest. Tekkai fought the urge to take the rosette right then. Oh, he wanted to plant that third eye where his skin itched for it, but it had taken months of forced withdrawal in prison to break him of his addiction to the Floating Worlds. He liked to think he still possessed a pinch of self-restraint.

With an extended finger, Tekkai traced an invisible spiral around his rosette, inching closer to touching it. "You promised me news of Ichiro."

"Immerse with me and I will show you the digital captures, as promised," Maeda said.

I need to see my son

, Tekkai thought.

And I also need the truth from Gama.

He picked up the delicate crystal rosette, slicked the back of the interface with his tongue and adhered it to his forehead. The tickle of sensation hit that sweet spot for the first time in ages. "Show me."

Maeda nodded, closed her eyes and interlaced her fingers again, entering a trance. Tekkai followed suit. He drew a deep breath and held it, disowning his flesh until he knew no existence save that single breath.

Then, he exhaled his soul.

As Tekkai immersed, the dark behind his eyelids flared into snow-blind brilliance, reshaping his sense of the world. A rotation of nine avatar skins billowed and shrank about Tekkai's point of reference, calling him to choose a body. Tekkai shed the default duplicate of his current physical form, his gaunt fifty-year-old flesh in the real world, and briefly donned the skin of the iron-crutched lame beggar he sometimes wore. In the end, he slipped into the young, barefoot incarnation of Tekkai of the Immortals, glorious in its strength.

Beneath the traditional

sennin

leaf coat, the tattoos upon his Immortal form pulsed with trapped power. Some, like the lion-maned

ki-rin

, had been inked by a prison tattoo artist onto his physical body. However, those replicas on flesh could not match these vibrant icons on his virtual form. Others, like the frog on the back of his neck, had no solid-world counterpart as yet. He had been saving those for the latter years of his sentence.