IGMS Issue 11 (20 page)

Authors: IGMS

I should wake someone else to see this thing, she thought.

But she couldn't bring herself to make a sound or even move to poke somebody. What if she frightened the man. What if he did this every night when no one was looking, and then scampered back inside the bark before dawn? If she made a noise he might stop coming out, and no one would believe her when she told what she had seen.

So she watched him in silence. His body rotated so his shoulder and arm were straight out. And when he got his right leg out too, he rotated even more, so now he faced outward. Both legs came free, and then both arms, and . . . and he was dangling, painfully it seemed to Eko, by his neck, for no part of his head had come forth from the bark. And without the tree holding up any part of his lower body, the boy struggled and wriggled but had no leverage. He slapped and pushed against the bark, but he couldn't get his head free.

Eko worried that he might be suffocating. Or strangling. Or simply helpless, and what would he do if he could never get his head out of the oak? Hang there till he starved? Or until some bear decided to eat him? If there were bears in the land of the thornmages. She had never heard of a bear in the Forest Deep, but you never knew.

By the time she thought of bears she was already halfway to the tree. Still none of the family awoke, so she was alone when she stood under the boy in the tree and tried to reach up to help him. She couldn't, of course, so she went back and woke Father, pressing her finger against his lips to keep him from speaking.

She led Father to the tree, and then showed him what she wanted, without saying a word. He lifted her and sat her on his shoulders. Now she could reach the boy's feet and help hold up his weight.

Now he could reach up his hands and push against the bark much nearer to his head. Eko could hear Father beginning to pant with the exertion of bearing both her weight and half the boy's. "Come out come out," she whispered. "The moon's about." The rhyme was supposed to be about the sun, but Eko was adaptable.

The bark didn't tear, it merely opened, or not even that, it simply receded so that his face emerged as if from water. He was not a beautiful boy. His face was stretched. His nose scooped downward and out as if it were some sort of bird's perch. And when he got free, he was pushing so hard against the bark that he toppled all three of them down into the meadow.

Still no one woke.

Eko got up and went to the boy. He was naked, curled up in the grass. She touched his shin. He gasped and quickly withdrew his leg as if her touch had stung him.

She sat down before him, looking at him, marveling. None of the stories said that the Man in the Tree was just a boy.

"Is that a dingle or a dong?" whispered Father. "Is he a man yet or not?"

Eko shook her head. It's not as if she knew anything about how a boy became a man. She was having trouble enough making sense of the nasty things involved in becoming a woman.

At the sound of Father's voice, the boy slowly moved his hands to his ears and covered them. Then he tucked his body into a ball, ears tightly covered, eyes squinted shut.

"He wants to be alone," Father whispered.

Eko nodded her understanding, but not her agreement. As if Father understood both messages, he crept back to the spot where he had been sleeping near Mother, while Eko continued to sit and watch.

Eko woke at the first light of dawn. The boy was gone. Instinctively she looked at the tree to see if it had been real or a dream.

Real. There was no manshape now. Nor was there even a scar in the tree where the boy had broken free.

The boy had not stayed to speak to her. Had not stayed for daylight. Somehow she had fallen asleep and he had crept away while her eyes were closed. It hurt deep inside her, to have been present at his -- what, birth? Emergence, anyway -- only to have him sneak away while she slept. She never heard his voice. More to the point, he had never shown a sign of hearing her, or remembering that she had helped him get free of the oak.

I didn't do it for thanks, she told herself. So it doesn't matter that he never said thanks.

Maybe he couldn't. Maybe he speaks only tree language now.

Or maybe he was born inside the tree . . . somehow. Maybe he was never human. Maybe

he

is the

tree's

clant. Why shouldn't there be trees that had the talent of man magery? Then the outself of the tree would ride inside the boy, struggling to understand the world around him.

Eko lay there, weeping quietly, until the others awake and saw that the Man in the Tree was no longer there. They were all so frantic with questions and disappointment that Eko could barely get them to listen to her as she told what she and Father had done that night.

"But you let him go!" said Immo.

"If he was done with being the tree's prisoner," said Father, "why should Eko have tried to make him

her

prisoner?"

All morning Father and Mother tried to restore the sense of frolic, but it was wasted effort. Everyone could see how Father grieved. The Man in the Tree really had been part of their family's life from his youngest memories. And now he was gone.

By noon everyone knew that it was time to go. It was no longer the meadow of the Man in the Tree. It was just an oak meadow now, and noplace special. Now other families could come here with no mysterious trapped man to frighten them. But

their

family, who had not feared the Man in the Tree,

they

would not be back to this place again in their lives.

As they walked home along the barely detectable track which was nevertheless engraved in memory, Eko thought she caught glimpses of movement in the woods to either side. Was the boy dogging them, keeping them in view? Was he hungry? Thirsty? What if he broke the rules of the thorn mages?

Ridiculous. The thorn mages surely knew where he had come from and would not begrudge him a sip or two from whatever stream they passed.

They emerged from the woods and began the long climb toward the pass. They had left too late in the day to make it all the way home, so they camped in a cold clearing high up the slope, where the ground slanted so much that Mother and Father tied the little children to sapling trunks so they wouldn't roll away in their sleep.

"Maybe this is how the man got caught in the tree," Bokky joked. "He was a baby that his mother tied to the tree and then forgot."

"I can't believe he's gone," said Immo.

Gone, but not far, thought Eko, for she had caught another glimpse of a shadow moving just at the edge of her vision.

The next day, if he followed them through the pass and down to the village, Eko never saw. And yet she knew that he had done it somehow, naked as he was, cold as it was. That's why, when they got home, she took a ragged old outworn tunic of Father's that Mother was saving to cut up into rags or maybe make into something for the baby to wear -- she hadn't decided yet -- and, along with a bit of her own dinner, left them at the edge of their potato field, in the shade of a slender oak sapling -- in case the boy had some particular affinity for oaks.

The next morning, food and raiment were both gone, and Eko could only guess where he had gone. Perhaps downriver. Perhaps back over Icekame. Or maybe he had flown away like a bird, or burrowed down into the earth to find the roots of yet another tree. Who could guess, with such a magical being?

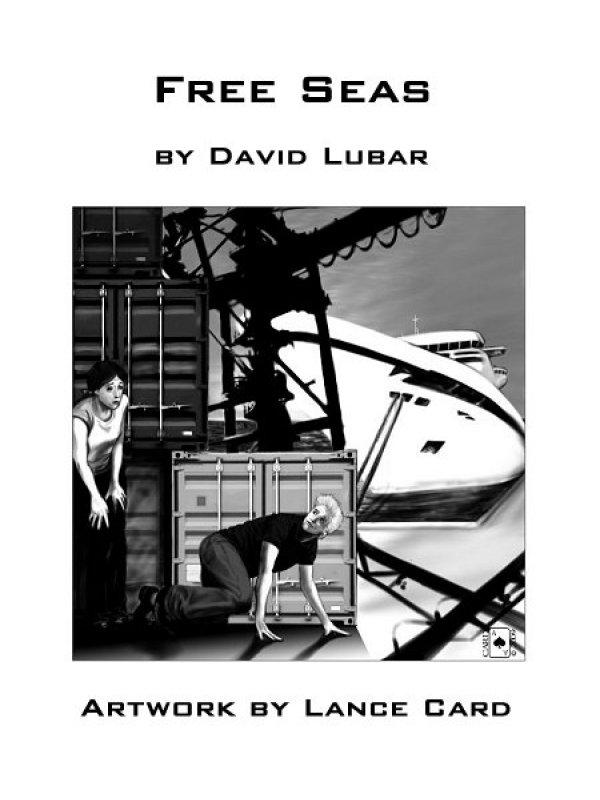

by David Lubar

Artwork by Lance Card

"Which boat is it?"

"Shhh. Quiet. It's Pace Cruise Lines," Andy whispered. He crouched down on the pier next to Mary.

"There. That's it," she said.

"Yeah. Good job." Andy felt a rush of adrenaline shoot through his gut when he realized they were going to do it. Not just talk and plan. Not just daydream. Really do it. There was the ship. He could see most of the name, except for a couple of letters that were blocked by a cargo crane. There was the P on the left, then the E on the other side of the crane arm, followed by CRUISE LINES. It was the ship Brennan Winston had told him about.

"Ready?" he asked Mary.

"You sure about this?" she asked.

"Yeah. It'll be awesome. We'll blend right in with the passengers. It's just for three days. But think about all that food and fun."

He crept toward the ship, trying to move silently on the old wood of the pier. He could hear Mary slipping along behind him. All they had to do was sneak down below and hide. Brennan had told him how to do it.

"It's real dark," Mary complained as they made their way up the walkway and onto the ship.

"Shhh. The passengers aren't boarding until tomorrow morning. Just follow me." Andy led Mary down below.

"What if we get caught?" Mary asked when they reached the bottom of the lowest deck, guided only by dim night lights.

"I told you, they won't do anything. We're minors. They'll just wait until the boat gets back to the dock and make us leave. Keep calm and they won't catch us. Okay?" Andy reached out and gave her shoulder a squeeze.

"Okay," Mary said. "I guess . . ."

The rocking of the boat woke Andy the next morning. "Hey, we made it," he said, nudging Mary's shoulder.

She sat up fast, looking startled, and he had to shush her again. "I need a bathroom," she said.

"No problem," Andy told her. "Put on your suit and we'll go up on deck."

Mary pulled off her shorts and top, revealing she'd worn her suit underneath. Andy grabbed his from his backpack. He noticed that Mary turned around when he changed.

She'll get over it

he told himself.

"Now be cool," he said. "We belong here. Just keep that in mind and nobody will pay any attention to us." He opened the door and peeked out. There wasn't anyone in the hallway. As long as they weren't spotted coming out of the storage room, there'd be no problem.

Andy braced himself to meet people. He knew the first moments would be the toughest. But all he had to do was nod and smile, or just ignore the other passengers. That would work. Adults expected to be ignored by teens.

You're on vacation

, he reminded himself.

They didn't meet anyone as climbed the steps from level to level.

"Must be early," Andy said.

There was nobody on deck.

"This is wrong." Mary grabbed his arm. "This is really strange."

"Relax," Andy said, though he had to fight to keep the calm tone in his voice.

"It's a ghost ship!" Mary stepped away from him and spun around, as if searching for something to prove her wrong.

"Mary, stop acting crazy," Andy said. "There's no such thing as a ghost ship."

"Yes there is. Look around. There's nobody here. Nobody. Just us." She ran back down the stairs toward the cabins.

Andy cursed and ran after her. He knew he had to calm her down before she got them both in trouble. He managed to catch up with her halfway down the corridor. "Wait. Look, everything is fine. I'll prove it to you."

He reached for the nearest doorknob, frantically trying to figure out what to do once he opened the door and came face to face with strangers. He realized he could just pretend he had the wrong cabin. That would work. And Mary would see that everything was fine. So would he.