Imperial (106 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

And the wife added: The ordinary concrete reservation houses.

Broccoli, over here, he said. Dates and palms, that’s Bard.

He was happy to get money twice a year from the casino. Their last distribution from the casino was almost four thousand dollars, and the check from the previous six months had been almost five thousand.

About the Cucapah he said: We’re not related. They’re just our neighbors.

I asked him what he had done for fun as a kid, and he laughed. His wife, who was extremely beautiful, with long red hair, said: It’s a bunch of bored kids with a whole bunch of back road.—And he said: Being a teenager, those were the days!

Yeah, said his wife. Your mother came by her grey hairs honestly, dear. She did.

There’s been a comeback with the language, he said. And fun nowadays involved basketball, movie night . . . He proudly named the names of various tribal organizations.

About herself, Diana Chino said: We were going to spend a winter in Idaho. But Mother didn’t like the cold. I was a white kid dropped into an Indian school. But now it’s better. Our son is as blond and blue as they come, and he has had no trouble.

Did the heat take any getting used to?

She said: We’ve got the fields around the house, so once the sun goes down it starts to dissipate.

I asked Mr. Chino whether he considered himself to be part of Imperial County in his mind.

Pretty much, we’re just Yuma people, he replied. We’ve been here a long time. Technically our tribe is considered an Arizona tribe. Farming has always been Yuma as well. Yuma thrives on lettuce. They use the land here sometimes. It’s all iceberg across the street. It’s darker green because it’s fresh.

He spoke of Imperial as if it were another country, saying things like:

Imperial has hayfields and so forth over there . . .

If you go through like Brawley, he said, it looks like time has stood still. Old-time El Centro is something out of the fifties. When I was in the Midwest, I would see houses and buildings like that

Do you ever go to Mexico?

We usually go to Algodones, she said. Sometimes we go to San Luis. I like to go get my vanilla for cooking. It’s real vanilla. You can get a screamin’ deal on Kahlúa.

How often do the

pollos

come through here?

She said: One of my friends on the west side, she says there are quite a few who come through. That’s why we have a lot of dogs. So of course the Border Patrol comes through. A lot of helicopters.

I asked about their water situation, and he said: We had the water-rights issue twenty-odd years ago. The tribe was given the water rights in federal court. Each member was distributed about three thousand dollars. We went to San Diego; we went to Mexico; we went to Disneyland! We had to sign over the land where the All-American Canal runs through.

He showed me his drawings and one of his swords. She gave me some of her home-baked pastries. They were kind, patient people, and I was sorry to leave them.

I asked him whether he had any vision for the future of the reservation. He wanted the Quechan to emulate the Morongo tribes up near Palm Springs.—They have a really high end outlet, he said.

Regarding Palm Springs, by the way, one of our favorite boomers, L. M. Holt, possessed an equally enticing sense of the future encompassing these

eight thousand acres of choice land . . . About 3000 acres belongs to the Government, and is being reserved temporarily for the use of Indians, of which there are five or six families in the valley, who are peaceful and valuable laborers for the white men who are now developing these hitherto unknown lands.

Chapter 106

THE ISLAND (2003-2006)

O

n the Quechan Reservation I had asked Cameron Chino about a section called the Island, and he’d answered: That’s always been where the black people live. So I’ve not really gone into the Island. There’s this levee road all through here, through the subdivision, and then it would turn easterly into another levee round into Bard. From that road to down

here,

that’s the Island. It’s pretty big.

It used to be all bushes here, said a black man named James Wilson. The All-American Canal busted a few things. Killed some woman on horseback, a real white girl.

(The Island really had been an island, once upon a time. Someday, perhaps, it would be again.)

Mr. Wilson was forty-five years old. I asked him to please tell me some of his memories, and he said:

Used to go swimmin’ in the water for fun. Had old pump irrigation. My first job was choppin’ cotton. Went away about fifteen or twenty years ago. We used to plant often, too. Had a twenty allotment. I must have been about ten years old. Used horses to plough. Then my Dad worked on the Southern Pacific Railroad. When I got a little bigger I went to work on a date farm. Still doin’ it thirty-five years later. They used to hire on wetbacks, but then Immigration got on them. Didn’t really affect me.

I own about seventy-nine acres. I grow a few date trees; I must have about eighty. Some people have a hundred fifty or a hundred sixty. Trees might be bigger over there in Coachella. Started putting in trees here about 1945.

Lemons came on pretty strong, and some grapefruits, too, here in Bard. Dates is pretty good right now. Look like a lot of date growing to move to Yuma.

What’s the best thing about living here?

Got a house and everything I need.

And what’s the biggest change?

Biggest change is all the big companies coming over.

He got electricity and water from the Bard Subdistrict, but paid the land lease to Arizona, because before the Colorado shifted, this part of Imperial County had actually been in Yuma.

THREE COMMENTARIES ON MR. WILSON’S DWELLING PLACE

Yuma has a split season, remarked Richard Brogan. Yuma very much grows in smaller plots than we do. Mostly Yuma is Colorado riverbed. They’ve got better soil. That’s completely corporate farming. They never shut down the cotton farming there like we did. The Winterhaven area, the Bard Subdistrict, that’s a separate area, and they voted to keep cotton in and they did. Bard relies on Yuma as their provider. It’s funny; they rely on Arizona time. There’s a lot of people that don’t even know a lot about Bard. They’re

different.

Kay Brockman Bishop, who had lived in Imperial County off and on since her birth there in 1947, and had even climbed Signal Mountain, had this to say about Bard: I don’t know a soul up there.

In October the flower-fields near the Cloud Museum were all chocolate-brown, furrowed and empty. But everything was lusher than elsewhere in the Imperial Valley, thanks to the proximity of the Colorado’s tree-packed gorge. The crystalline beauty of the palm trees in their staggered rows reminded me of Coachella. Cooling myself in a rectangle of evening shadow elongating out of Imperial Date Gardens, I discovered that it was already that moment before dusk when every furrow is sharp and clear. At the side of the road, in flatbeds, bunches of handpipe were stacked like bundles of asparagus. Driving straight into the evening sun, I found Bard full of wild palms, grasses and shrubs. Now I was almost at the Salamander Mobile Home park with its attached bar. And Imperial Date Gardens had fallen entirely into shadow.

By the Cloud Museum I looked west, and between two palm-rows the sun basked like some strange squash or maybe a fallen grapefruit. It had melted into a pink stain between mountains by the time I’d reached RANCHERO DE LUX DATES. The Island lay already under the rules of darkness.

How many people on this earth truly know Imperial County? And of those, who knows Bard? And even to a good portion of Bard’s inhabitants, the Island remains unknown, secret, like so many other subzones in the entity which I call Imperial. When I left James Wilson’s homestead, the night was as thick as cloth, and his aged father sat dreaming under a tree. This was Imperial, center of all secrets and therefore center of the world.

PART NINE

CLIMAXES

Chapter 107

THE LARGEST IRRIGATED DISTRICT IN THE WORLD (1950)

The extent of Alta California in ancient times was altogether indefinite.

—Samuel T. Black, 1913

I

n those days Imperial County’s stationery proclaimed itself

The Largest Irrigated District in the World.

Imperial County, and much of the rest of Imperial itself, had also become

The Winter Garden of America.

By twenty-first-century standards it remained curiously undifferentiated. Exactly a century after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo there was still no border wall, of course, and in that same year, 1948, the population of the county seat, El Centro, was only five hundred more than that of Brawley, whose thirteen thousand souls comprised a respectable enough crop. But please don’t think El Centro wasn’t on the map; in one of his bitterest detective novels, published in 1949, Raymond Chandler generously gave one of his characters, who got murdered with an icepick, seven business cards, each bearing a false address and telephone number from that city.

The county as a whole held more than sixty-two thousand people, which is to say that it was still, by the urban standards of my own time, empty. Coyotes remained

a serious menace to sheep during the lambing period.

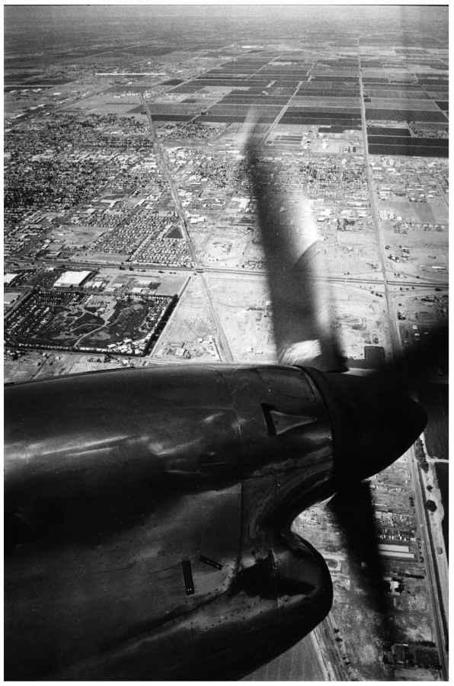

Although it was the ninth-largest county in the state, only one-half of one percent of all Californians lived there. But fly high enough and not even Los Angeles will show any people! Los Angeles’s muted blue-grey coolness, where skies and concrete are often the same, must have been blue-grey even before the foundation of that city in 1781. Ladies and gentlemen, hold onto your hats! The airplane (a chubby little plane which wears our American flag and the twin legends

TRANS WORLD AIRWAYS

and

LOS ANGELES AIRWAYS

) rises into a grey cloud through whose weave I can see with great distinctness the breakers of the Pacific Ocean; they’re as white as the sclerae of your eyes. Here we are, coming in from above a long white wave; we’re suspended directly above and perpendicular to the not quite infinite boulevard of trees and tree-shadows like ranks of rockets shoulder to shoulder. Around us and below us lie more trees, grassy rectangles, bungalows; this is the sea-edge of Los Angeles at midcentury. Ascending into the fog until these details are quite lost, we spiral into brighter and whiter air. We break through, proceeding southeast over a cold white desert of clouds. After awhile we pass a many-fingered blue handprint which admits our vision all the way down to earth. Here’s another hole. The clouds are riddled now; they won’t hold up much longer. Below me, the darker blueness of the San Gabriel Mountains parts the sky. The coast, brown and blue with white roads on it, is long gone, left to its own fog-dressed aridity. The hills below are fuzzed with blue-green trees, and sandy valleys of greenish-ocher lie between them. In effect, we’re in the Rothko paintings of 1948, whose shapes frequently remain circular and oval; we haven’t reached the field-rectangles yet. But the sand-patches are already getting bigger; and the vegetation’s taking on a worn look. And now, beyond the sharp-edged mountains, I see deeper vermilion than I’ve ever met with. If only I knew how to tell you how beautiful it is! The valleys go grey; the blue-greenness of the high hills is quite gone. This really could be Mars. Farther ahead the land is lower, paler, brighter and flatter: Imperial.

Yes, even after a century of irrigation, settlement and road-building it’s still almost otherworldly, with here and there a small simple grid of streets, houses laid between the squares like clusters of glass-shards—how they sparkle! Here’s a complex of field-rectangles blown white and grey with dust. More field-grids lie ahead, still greyish but a bit grey-green, too:

WATER IS HERE

. The Salton Sea is an inviting toy pond in the middle of them. According to the Ball Advertising Co., this place,

235 feet below sea level, is rapidly becoming one of America’s most popular water sport and fishing areas.

Shields Date Gardens explains that its salt content is presently

about the same as the ocean.

Never mind that trend; there will soon be launching facilities for power boats! The latest issue of

National Motorist

is thrilled to report that

low barometric pressure and greater water density make the Salton Sea the fastest body of water in the world for speedboat racing.

No wonder that by 1960 the number of visitors to the Salton Sea’s state beach park will surpass those to Yosemite. A booster from 1962 assures me

: At our little desert hideaway near Mecca, on the North Shore close to the Salton Sea, we have a beautiful artesian well which flows copiously all the time, much to the delight of the nearby palms, tamarisks and mesquites.

From my post-Imperial vantage point, this tale is equivalent in dreamy fantasy to the following:

They had a house of crystal pillars on the planet Mars by the edge of an empty sea . . . Afterwards, when the fossil sea was warm and motionless, and the wine trees stood stiff in the yard, and the little distant Martian bone town was all enclosed,

the Martian Mr. K liked to read from his metal book with the Braille-like hieroglyphs, stroking it so that it sang to him; and sometimes he would compose his own chants, such as—imagine! Water, on Mars! Imagine a Salton Sea around which tourists actually wished to play! Fly over it, and its blueness darkens eerily. Everything I see is so greyed up or down by dust that it might as well be a black-and-white photograph; in fact, let’s say that it is, because then it will never change. To the extent that Imperial is actually a Rothkoscape it surpasses my colorblind comprehension with its infinity of half-hidden tonal changes beneath a field of seemingly solid color; precisely this makes the Salton Sea so alive; but I’m not capable enough to render this phenomenon for you at all, much less in perpetuity (nor was Rothko himself; his black, black panels in the stiflingly ominous Houston Chapel have already begun to fade), so let’s keep this snapshot of Imperial simple; just the facts, ma’am. A waggling line of whiteness like a single breaker extends far out into the sea from a turbid zone near shore: subaqueous mudpots, I presume. In 1950 more of them would have been above water, not unlike

Salton City, a bustling young community of modern homes.

And Imperial radiates around me in every direction. What is Imperial? Whatever it is, it is all one. (Rothko, 1943:

A picture is not its color, its form, or its anecdote, but an intent entity idea whose implications transcend any of its parts.

) To my left I can see into Riverside County, a part of which, no matter what the state of California asserts, belongs to my Imperial; here is how a civic booster tells that story:

One of the great sagas of the Old West took place in the twentieth century. It was the transformation of the Salton Basin into the rich winter gardens, date groves, and fabulous resort and vacation centers of the Coachella Valley.

How strange! It’s as if the Coachella Valley had nothing to do with the Imperial Valley! As you know, I subscribe to all the opinions of Edgar F. Howe, who therefore might as well be looking out the window beside me; here is what he wrote in 1910:

We can see today more clearly the possibility of building a new Egypt. We can see the possible unification of Imperial and Coachella Valleys in a continuous garden from the Mexican line to the mountains which cleave Southern California in two parts.

A continuous garden indeed—the Winter Garden of America! But in midcentury that still hadn’t happened, not quite.

From the air,

two geographers will report in 1957,

the Coachella Valley looks much like the Imperial, except that the Imperial has solid blocks or irrigated greenery between its eastern and western canals, whereas the Coachella has only smaller and scattered irrigated patches.

Never mind. We won’t go to Coachella for a few paragraphs more. Instead, we begin to descend toward the field-squares to the south, which take on more greenness the closer we get; we’re coming into Brawley and Imperial. (Brawley’s slogan:

Where it’s Sun-Day every day!

Why doesn’t this apply everywhere else in Imperial? Take it up with the Ball Advertising Co.) Along the perimeter of these emerald and chocolate squares, a thin silver glint of water catches the light like tooling on a leather book. And over there’s the New River, looking strangely tropical in its green-frizzed gorge; it’s the only uneven thing in sight. How badly do you suppose it stank in 1950? (Worse than in 1940; better than in 1960.) There’s Signal Mountain far away, squat and blindingly mysterious over the green, green fields. Off to the left I see Calexico, which

is rightly called the “city of air-conditioning,”

and which offers us

the annual Dove-Hunters’ Fiesta, the Wine Tasting Fiesta, the Cotton Carnival and other Mexican and American holidays. One would think that every day is a fiesta on the exciting Mexican-American border!