Imperial (102 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Did you know who Imperial County’s truest friend is?—Why, Los Angeles.—On March 28, this disinterestedly altruistic neighbor, as represented by a certain G.P.C., Secretary and General Manager of her Chamber of Commerce, dictates a letter to Congressman Dockweiler in Washington, D.C. Los Angeles informs her representative that she opposes the dispatch of any federal labor conciliator to the Imperial Valley in this matter of the cantaloupe strike, because

the temper of the Californian or any other American under such stress

will lead to bloodshed. Los Angeles may not think that such a bad thing.

Instead of a kid glove, we need an iron hand . . . These communistic leaders must be deported and the soviet propaganda stamped out.

Their strike will be defeated, of course; and in 1935 we see a Mexican field worker in a white straw hat and a bandanna about his throat on the verge of leaving for the melon fields, his left hand hooked in his heavy belt, whose buckle is square, his right arm hanging loose, his trouser legs tied tight over his shoes at the ankle. Grim and wary, sweaty and tough, this young man clenches his mouth, gazing past us. Here comes his competition: Between June 1935 and August 1936, more than eighty-six thousand Dustbowl refugees arrive in California. (Now for the important news! By mid-July 1936, the Imperial Valley has shipped seven thousand nine hundred and ninety-three carloads of melons in seventy-two days!) By March 1938 there will be a hundred and twenty thousand new refugees.

A white man from 1935, stubbled, in bib overalls, stares not quite toward us from the Imperial Valley. His eyes are pits of shadow. His neck is bent and there are wrinkles in the bridge of his nose. The shadows catch his cheekbones. There is nothing behind him but solid tan, like some ancient badly fixed photograph of an Imperial landscape.

His day may be coming; the growers surely prefer him to alien Reds! For by the autumn of that year, broad and sinister motives have infected even the hinterlands of Los Angeles: Citrus pickers,

most of whom were Mexicans,

dare to make demands—rejected since winter citrus is small business anyway.

That Orange county should be chosen for this purpose showed very definitely some deeply laid plot. The pickers have been well paid . . .

at five and a half cents per box. They dare to ask forty cents an hour for a nine-hour day, a day’s work being thirty boxes; after that, they want seven cents a box. The confrontation builds until July of 1936, when strikers with clubs, knives and chains attack picking crews and packing-house workers. Both sides suffer injuries; hundreds arrested.

Interrogation of the arrested rioters showed that only four per cent of them are American citizens.

From 1936 a man in work boots and corduroy pants sits in the driver’s seat of his square, grimy vehicle, his face blasted white by the Coachella sun. The silhouette of his wife (only the lenses of her spectacles can be seen) lurks in the passenger side, hunching toward him, or perhaps just toward the center of the cab, which is farthest from that hot light. They are hoping to be taken on picking carrots. I suspect they have already found, as had the author of the 1936

Motor Tales and Travels In and Out of California,

that

disappointment was in store in the Imperial Valley, for El Centro was reached during a period of intense heat.

If they do get jobs, I hope they remember to demean themselves submissively; for by September the Associated Farmers will be beating and gassing white strikers up in Salinas.

The essence of the industrial life which springs from irrigation is its democracy.

In 1937, when they complete Barbara Worth Junior High School in Brawley, a Mexican pea field worker stands in front of his shack, whose cardboard is peeling from the outer walls; in the darkness, a small girl peeks from the doorway, clinging to it; and the man stands mournfully with one foot on the tailgate of his vehicle, holding a swaddled baby. It is March and the peas have frozen, and he does not know what will happen. Who cares? There’s only a four percent chance that he’s an American citizen.

“When a person’s able to work, what’s the use of beggin’? We ain’t that kind of people,” said elderly pea pickers near Calipatria.

Is that so, Okies? Your wish is our command! Caption to a Dorothea Lange photograph (#LC USF34-16338-DC):

March 1937. Drought and depression refugee from Oklahoma now working in the pea fields of California. She has picked cotton since the age of four. Imperial Valley, California.

Of course not everyone will be as lucky as she. In another Dorothea Lange photograph, a skinny man in a beaten-up broadbrimmed hat sits with drawn-up knees on a ridge of dirt, with planted furrows receding to the horizon, whose righthand edge is marked by the commencement of a single upslope which may well be Signal Mountain. Clasping his hands, he looks away from us. His cheeks are wrinkled and his neck is corded. The caption:

Jobless on Edge of Pea Field, Imperial Valley, California, 1937.

(Dean Hutchinson’s notes, sheet 4: Doc. W. F. Fox County Courthouse El Centro County Health Officer Thursday A.M. Apr. 5th 1934. Camp sanitation pea fields hasn’t changed in last 4 years—no improvement. Industry itself has developed very rapidly same time. Tremendous influx of migratory labor from district to district in Calif & Arizona

...

)

And they trek into California,

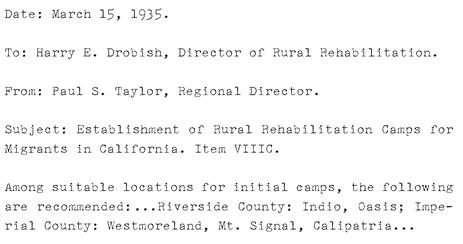

Paul S. Taylor told the Commonwealth Club of California,

these California whites, at the end of a long immigrant line of Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Negroes, Hindustanis, Mexicans, Filipinos, to serve the crops and farmers of our state.

Taylor calls them

a rural proletariat.

Imperial embraces them, and in 1937 we find this paean of welcome in the

Brawley Daily News:

Jonathon Garst, Regional Director of the Resettlement Administration has declared that the migratory camp for Brawley is to be built despite all the objections that have been raised.

Mayor Carey and others wanted to know why they were not consulted. Garst asserted that he was more interested in the people on the “ditch banks” than the people of Brawley.

The growers declared that experience had demonstrated that the class of persons found on the “ditch bank” camps are not suitable for field work, such as thinning and cultivating lettuce. They might be used as pea pickers in some instances—but the season for this class of labor is short.

In other words,

Water was in the ditches, seeds were in the ground, green was becoming abundant, and the whole area was dotted with the homes of hopeful, industrious, devoted persons.

The club motto is, “The aim if reached or not, makes great the life.”

In 1946, the College of Agriculture at UC Berkeley will conclude that

the seasonal farm workers . . . continue to present a major social problem.

Fortunately, this story does not end unhappily for all parties: A historian of the period concludes that

the Imperial Valley authorities enjoyed an unlimited range of power.

And now; and

now . . . IMPERIAL COUNTY SHOWS RAPID INCREASE

. . .

We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

In 1940, Imperial County’s gross cash income from agriculture achieves twenty-one million dollars (three point one two percent of California’s total). Out of California’s fifty-eight counties, Imperial is number seven for cash farm lucre!

Why, I would be sick to my stomach if I rode down that valley in California, over those long miles owned by one man.

And here comes a second happy ending: Japan bombs Pearl Harbor, and the Okies’ problems explode into bits! They can join the army or work in a factory . . .

What about the Mexicans? I think we all feel sorry for ’em.

Chapter 100

BUTTER CREAM BREAD (

ca.

1936)

O

nce upon a time it was indisputably true that

Butter Cream Bread enriches every recipe in which bread is used . . . Baked in the Imperial Valley by Cramer’s Bakery.

And in that fairytale time, if a good Imperial Valley housewife were to prepare a dinner with proportions for fifty guests, she’d lay in twenty-five cantaloupes, six quarter-pounds of butter, twenty-five pounds of roast pork, four average-sized cakes or nine average-sized pies, and seven quarts of ice cream. What does this tell us about the conviviality of the epoch, not to mention its prosperity for those who did not have to camp out along the sides of ditches, its ideas about nutrition, its level of physical activity (for we are fatter than they were)?

If I could only eat a slice of fresh-baked butter cream bread, then I would

know

the American Imperial of that time, because I could taste it. But just as Baja’s fossil oysters, some of them two feet long and twenty pounds heavy, were expended in making brickmakers’ lime, so American Imperial’s butter cream bread got eaten up; nobody fossilized any of it for my private museum; Imperial hurtled along toward me, not imagining that it existed only in the past.

And in material advantages they are already well supplied.

Chapter 101

COACHELLA (1936-1950)

D

r. John Tyler came to the Coachella Valley in June of 1936. The following month, a Riverside County woman trapped two mountain lions.

I met Margie in the dental office, he told me. I came down and I worked on a percentage basis and a small salary for Frank Purcell, the established dentist. We got married in 1938. Practically the only time that I considered moving away from the area was a very short period of time in 1936 when the dental association were trying to locate dentists. And they had places like Fallbrook that had no dentists. When I came here, Frank Purcell and Rufus Choate, we had four, there were five dentists operating in the valley but when I married Margie I decided to stay put. With the aqueduct in here and all the workers, we had lots of work. The valley was growing, like mad.

It would hardly surprise me to learn that Dr. Tyler

decided to stay put

not only for the sake of his career, but also on his wife’s account; for she was born on a ranch in Coachella in 1916. At any rate, when I asked him what made the area special, his reply expressed an elderly person’s concerns: I think it’s the climate. I think it’s the heat. I think that air-conditioning has made it practical so that people can live here all through the summer, and people who have afflictions of the arthritic nature feel better than they ever have in their lives.

The main event in the first year or two that I was here, he said, was the arrival of the workers who were building the Metropolitan aqueduct going to Los Angeles, and the town was flooded with the wives of the aqueduct workers and so on, and for awhile getting a place to stay was a big thing. They came in literally by the hundreds to work on the aqueduct.

Where does it begin? I asked, wondering whether he would answer,

The Colorado

or

Imperial County,

but he simply replied: The aqueduct brings water from Parker.

And how did you feel about it?

Well, the local people, most of them, accepted the workers pretty well. At that time we still depended on wells, so we didn’t mind too much one way or the other. But there was a lot of contention about the All-American Canal. They had planned that canal to go up to Coachella and they wanted the farms up here to be paying to furnish water for Imperial Valley for some time.

Did the Imperial Valley seem close or far away?

No, in those days distances seemed much further, said Mrs. Tyler.

Was Imperial poorer than Coachella?

Everybody was poor, said Mrs. Tyler, and Imperial wanted us to help pay for the canal when we weren’t yet getting the water ourselves.

When did you feel that Coachella really started to boom?

There was kind of a boom in the twenties, before the Depression, said Mrs. Tyler. People building nice homes for tourists. Then that stopped. The farming industry burgeoned after the war. But the real boom, I think it was in the early thirties, and it had to do with air-conditioning. We had swamp coolers and people could live here without living too uncomfortable. When air-conditioning came in, it really burgeoned. The swamp coolers were a great help. As long as it’s dry and not humid, they work beautifully.

Her husband put in: By the time we got married, well, the development was going so rapidly that building could hardly keep up.

Was the Date Festival pretty well established by then?

Well, it didn’t start until the thirties. The first festivals were held in the Indio Park. And I don’t remember exactly when it started at the fairground, said the old woman, wearily shaking her head.

I think the Indio Civic Club sponsored some of the early events that were in the park there, said her husband, trying to be helpful.