Imperial (98 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

How could Americans settle here?

They had parcels from the Colorado River Land Company. But of course no foreigners had rights here, only Mexicans. Cárdenas bought out the company at eighty pesos per hectare and also started the

colonias

at that time.

What was life like on the

ejidos

then?

The first

ejidos

were like kibbutzes. They all worked together. In 1939 they told Cárdenas that they didn’t want to work collectively anymore, since there had been many fights. So private property was introduced. One hectare got donated for a park.

“THERE WERE NO GUNFIGHTS”

The scope, effectiveness and good faith of Mexico’s agrarian revolution has been debated since the 1960s. Without exception, the

ejidatarios

whom I interviewed in Mexican Imperial considered themselves the beneficiaries of Cárdenas; and almost without exception, they expressed satisfaction with their lives, which they tended to characterize with the word

tranquilo.

They personalized that President and told anecdotes about him, such as the following, which I heard from the proprietress of a small highway restaurant south of Mexicali:

Cárdenas came here

177

and saw a house falling down and a new car in front of it. He got upset.

She adored him.

178

By one account, Cárdenas granted fourteen million hectares to almost a million campesinos. About a hundred and sixty-eight thousand of those hectares had been Harry Chandler’s.

Not all the grants stood. Down south in Morelos, the heartland of the Zapatista revolution, Cárdenas passed out many acres, and yet, thanks to disputes between villages, rising land values and growing populations,

ejidos

there frequently shrank, both in total extent and in plot size. One historian concludes that by 1943, Zapata’s hometown

was in desperate straits.

Another source writes that because many Mexicali campesinos lacked the means even to purchase water, much less seed and other supplies, by 1943, not even eighteen percent of the valley’s

ejido

fields were being worked. Meanwhile, another scholar explains that

Cárdenas’s agrarian reform paid off because both output and productivity rose.

I cannot speak on the current fortunes of Zapata’s hometown. But Mexicali’s

ejidos

continue even today to dream their rich green Imperial dreams.

When Cárdenas was President, explained a rancher’s wife in the

ejidos

west of Algodones, he divided up the land and gave it to the families who were already living here. When the first father died, it went down to the family. Our rancho was in the family since the time of Cárdenas. On the twenty-seventh of January, that’s when they got the ranch. That was when that group of men took over all the factories. There were two factories there where they took care of the wheat and the cotton. They stormed the factories here and that’s when Cárdenas started this system.

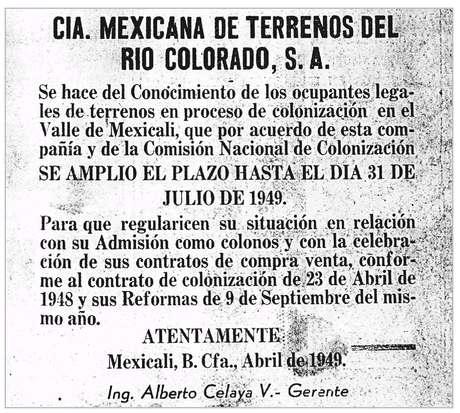

Circular regarding the sale of Colorodo River Land Company plots

I asked how her life was, and she smilingly replied:

Tranquilo.

Cárdenas was rapid and determined. Between March and August 1937, nearly a hundred thousand Colorado River Land Company hectares had already been confiscated and converted into about forty

ejidos.

The confiscations continued. In 1938 the company’s irrigation canals were nationalized. Chandler and his partners received compensation in annual payments which finally ended in 1956. After an investment of four decades, they gained nothing and lost nothing. In 1972 the company’s Mexican receiver finally dissolved.

As I write this, there remain more than two hundred

ejidos

in the valley.

Yolanda would have been born shortly after these events. In 1937, Hermenegildo Pérez Cervantes would have been thirteen. His account of what happened was both more local and less enthusiastic. He said to me:

In 1937, that’s when they divided up the land. So basically Cárdenas expropriated the land. That’s when people started arriving from Michoacán, Guanajuato, etcetera. That’s when you started to see campesinos. That’s why you see the

ejidos

with the names like Zacatecas, Guanajuato, because the people came from there. There were no gunfights when it happened. There were some farmers who were renting land from the Colorado River Land Company. The expropriators took the land from them, too. Well, there was a sit-in by these people with their families in front of the Governor’s Palace. They had a kiosk where they were giving speeches to the public. They were there a month and a half at least. They sent a delegation to Mexico City to talk to the government. I was really little; I really didn’t know what opinion to have about them. But what I heard was that somebody had taken their land. So people were sympathetic toward them. The business owners sent them food. And the women, they had a little wood fire and they made their dinners right there. And finally they were given other land. The few who had bought land from the Colorado River Land Company were not expropriated.

I asked him if he believed Cárdenas to have been a great man, and he assented, but not emphatically; he did not even say

claro,

meaning

of course.

This old survivor who so happily remembered the marching band created by that Chandler ally or entity, the Industrial Soap Company of the Pacific, told me about 1937 without Yolanda’s smiles. But, after all, he was a city dweller, no

ejidatario.

In his great novel

Under the Volcano,

which is set in 1938, Malcolm Lowry describes Mexico with cynical sadness. For him, the era of Porfirio Díaz continues in the Cárdenas years:

Yet was it a country with free speech, and the guarantee of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness? A country of brilliantly muralled schools . . . where . . . the land was owned by its people free to express their native genius? A country of model farms: of hope? It was a country of slavery, where human beings were sold like cattle, and its native peoples . . . exterminated through deportation, or reduced to worse than peonage . . .

In Mexicali there was an official of the Tribunal Unitario Agrario named Carlos E. Tinoco. With his nearly shaved head, his moustache and goatee, he had a somewhat Leninist appearance. He said to me: So it’s important to understand first that Cárdenas came out of the Revolution. One of the things that gave rise to the Revolution was land inequality—a lot of land and few owners. So there were social revolutionaries like Madero and Zapata, and they were interested in turning that around. And that’s when they started to have Presidents who came from the ideals of the Revolution. Zapata was not a campesino. He was a big landowner. His land was divided up among the campesinos. He took up arms. His motto was: FREE LAND; LAND OF LIBERTY. It kind of just happened that when Cárdenas was President, they had the opportunity to divide up the land. Cárdenas basically left the large landowners without any recourse. I think that was a little heavyhanded. A person could get four hectares to eight hectares, and the landowner would have to give it up.

Cárdenas helped the whole country, Señor Tinoco continued, but especially people living in Baja California. In the United States and in most of the states of Mexico, the division is not equal. Baja California is just one of the places where a parcel is almost always twenty hectares, perhaps because there are so many plains and a lot of water, so you can irrigate more places. But the actual motives for why the parcels are twenty hectares, no one knows exactly.

When you go into the

campo

now, he said, what is the average farm size? Still twenty hectares. And, at least before 1992, you were not allowed to divide up your parcel. It’s called the indivisibility principle. You go with your group of friends to form this

ejido

and then if you get married you put your spouse’s name as the inheritor. If you divorce, that’s a different problem. If your name is on the paper, you don’t have to leave it to your wife but to whomever you want to. So if you got divorced the wife might have no right to the land,

179

or if you had several children, they could not break up the property. The order usually goes: You leave it to your wife, your concubine, or your children, or your parents. But you still can’t subdivide it.

“ALTHOUGH ACCURATE DATA ARE LACKING”

After Cárdenas, Camacho performed a tightrope dance between

ejidatarios

and landowners, and for better and worse the pace of redistribution slowed. Landowners and

ejido

families were encouraged to reconcile.

Southside was and perhaps in part remains (likewise Northside)

a country of slavery;

and yet I tentatively believe that in these years the borderlands of Mexican Imperial did indeed offer

a country of model farms: of hope.

Astonishingly, even the American Ambassador thought so.

On Northside,

although accurate data are lacking, the belief is rather widespread that concentration of ownership and control is increasing.

On Southside accurate data are equally lacking, but the perception, thanks to the Revolution and especially to Cárdenas, is the opposite.

Should we grow food as efficiently as possible, which will benefit consumers with uniform quality and low prices; or should we support the family farm? Posing the dilemma in this way creates the illusion that somebody in power has actually made a choice, when of course it’s all (let’s pretend)

market preferences,

hence nobody’s fault when the Okies get tractored out.

There are many who do not know they are fascists but will find out when the time comes.

But in Mexico someone

has

made a choice.

Imperial’s delineation grows unbearably real: Northside has gone in one direction, Southside another.

Chapter 98

THE LINE ITSELF: JAPANESE ADDENDUM (1941-1945)

“Well, that’s the way the world goes,” the shadow told him, “and that’s the way it will keep on going.”

—Hans Christian Andersen, 1847

W

e rotated crops, Edith Karpen said. Part of the time there were melons. Between that there’d be alfalfa to rebuild the land. Milo maize, that was a summer crop. Kawakita was one of them that leased our land periodically to raise melons. Jack didn’t raise them; he leased the land to people who raised them. Kawakita was very pro-Japanese when the war broke out. His son Meatball went back to Japan, and he had these radio broadcasts against the United States, and he was held responsible. After the war, they held a trial for him. At least one daughter went back to Japan because he didn’t want her to marry an American Japanese.

Were most people in favor of locking up the Japanese?

They were all in favor of it. My friend Harold Brockman had a friend who was Japanese who was interned, and he stored all his things in Harold’s garage. They thought there was a real threat to the Valley, because they thought the Japanese might come up through the Baja. So they took training so they could recognize the silhouettes of Japanese planes, and they used to patrol the All-American Canal. Jack used to take a gun and go. I remember sitting eating breakfast in my kitchen and the rain was pouring down; we had harvested alfalfa and they had put up temporary fences around the alfalfa to keep out the sheep, and suddenly I heard all this racket when Jack was out on patrol, and the sheep were milling all around the house and I had the radio on and they had sunk one of our big ships, the British ship, too, and it just looked so threatening to our forces, I just sat there and cried. I had a brother who was taken prisoner.

Chapter 99

BROAD AND SINISTER MOTIVES (1928-1946)

Finally, the Committee recommends that a group of representatives of the agricultural interests of California wait upon the Governor . . . to advise him of the broad and sinister motives and objectives of the recent labor disturbances and their serious threat to California’s greatest industry and to urge upon him the necessity of using every means for the protection of the State.

—Report of the Special Investigating Committee, 1934

“CALLING WORKERS FROM THE FIELDS”

A dusty old truck, squarish with round headlights like spectacles, poses at the edge of an empty dirt road. A small army of slender young men, all but one of them wearing pale, close-fitting mushroom-shaped hats, stands on the truckbed, leaning up around the cab to envelop this sign: DISARM THE RICH FARMER OR ARM THE WORKER FOR SELF-DEFENSE. The capless one has sleek black hair; he looks boyish, Hispanic. The others are harder to see, their faces gone to shadow beneath their caps in that harsh white California light. On the back of the photo someone has handwritten:

These Mexican men

180

are out to canvas

[

sic

]

the country side

[

sic

]

for people working in the cotton fields.