Imperial (94 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

“BOLDER THAN BRITISH DREAMS OF EGYPT”

With the practically limitless Boulder Canyon power now available, the city has been placed in a still more advantageous position.

These words, of course, issue from the mouth not of El Centro or Coachella, much less Mexicali, but from Imperial’s foe, lover, or threatening friend, Los Angeles.

No doubt there was trickery involved against the yokels of Owens Valley, maybe even a little rough stuff (Tamerlane’s warriors gallop into the square); but I’m sure that the following words from

Babbitt

apply to every man involved, from the lowest-paid construction worker right up to Mulholland himself:

Then he goes happily to bed, his conscience clear, having contributed his mite to the prosperity of the city, and to his own bank-account.

Besides, the yokels weren’t compliant. They kept on with dynamite. In return, Los Angeles was forgiving, merciful. In 1934, the city bought out the ranchers whom it had ruined. So that was the year of the last apple crop.

Today the trees that bore that crop are again white with blossoms, but the petals of these blossoms will fall on parched ground. The boughs will never more bend under their load of fruit. The water is gone. It flows southward to the Great City. Be it so. The sin is not ours.

What next? Another aqueduct.

Imperial County, tranquil and removed, continues to dream her dreams of lucre.

The boughs will never more bend under their load of fruit

in the Owens Valley; but to the Imperial Valley, more water than ever will come. And so Imperial County prepares to draw up her yearly agricultural report.

These statistics were compiled by the Imperial County Board of Trade under the supervision of the Board of Supervisors,

explains a sheet entitled “1928 Statistics.” So far, so good; this is how the county wants others to see it.

Anyone wishing further information concerning Imperial Valley farm lands and lands affected by Boulder Dam project may write Imperial County Board of Trade, Court House, El Centro,

again, so far, so good, but here’s the peculiar part,

or may obtain it at Imperial Valley desk located in Chamber of Commerce Building, Los Angeles, 12th and Hill Streets.

THE DESERT DISAPPEARS

Was that last hint too obscure? All right, then: In 1923, while the Chinesca burned and Imperial County readjusted its borders one last time, William Mulholland and company boated down the Colorado.—And Mulholland said: Well, here’s where we get our water.

Sixteen more survey parties went out under his authority, investigating the respective merits of Boulder Canyon, Bull’s Head, Shaver’s Summit, Picacho through the Imperial and Coachella valleys; please don’t think that Los Angeles wasn’t interested in the Colorado . . .

THE NEXT TWIST

Meanwhile,

with what amounted to secrecy, . . . my deputy and I went by auto over the then-unpaved mountain and desert highway and onto the plank road through the sand dunes to Yuma.

So we are informed by Shelly J. Higgins, attorney for the city of San Diego. It was summer, he complained—but when wasn’t it summer in Imperial? Imperial is this: When you come out of the July sun, your shoulders slowly relax.

Early one morning—the sun was working itself into a white-hot rage . . .—we went for a distance up river and piled rocks into a cairn and in the middle we placed our legal notice of filing for water and power, stuffed into a tin can.

San Diego thereby claimed a hundred and twelve thousand acre-feet per year of Boulder Dam water.

Chapter 92

THERE IS EVEN EVIDENCE OF A SMALL FRUIT ORCHARD (1931-2005)

It is well known that civilization demands water, and that it shifts in pursuit of it, because the former is dependent on the latter.

—Al-Biruni, A.D. 1025

G

ale Robbins, slender, sleek and cold silver, perhaps a redhead in “real” life, smiles in an oval of perfect teeth and dark lipstick, her eyes expressionless beneath arched brows, the orchestra playing behind her. Four handsome, smiling men in dark suits groom her as would ants their queen, the two seated ones in the foreground kissing one wrist apiece, the other two, standing, touching their goblets to the air around her naked shoulders—ah, invocation; oh, hieratic pleasure! And it is all happening in Los Angeles. Just think how much water it all takes!

In November 1935, consumption of water is two hundred and two second-feet for domestic use, forty second-feet for irrigation. In November 1936, Los Angeles is up to two hundred twenty second-feet and sixty-five second-feet, respectively.

Of the total consumption for the month

of November 1936

(284.9 second feet), 221.3 second feet was drawn from the

Owens Valley

aqueduct supply and 63.6 second feet from the Los Angeles River supply and local wells.

Thank God for Mulholland and the Owens River! Daily flow from that watercourse and various Owens Valley wells through the Los Angeles Aqueduct varies from three hundred and fifty second-feet in November 1935 to two hundred and forty-three second-feet a year later. Los Angeles keeps pumping. Owens Lake has long since become a dustbowl. By 1941, four of Mono Lake’s tributary creeks have also been sucked dry.

Principal products of Los Angeles, 1942: aircraft, petroleum, motion pictures, women’s clothing. Don’t those require water, too?

In 2005 an Owens Valley tourist pamphlet which bears self-congratulations from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power on the inside front cover

(We’re proud to be a major recreation provider in the Eastern Sierra!)

passes on the following must-see hiking vista:

Higher up the road notice the mine site and ranch on the left; there is even evidence of a small fruit orchard here.

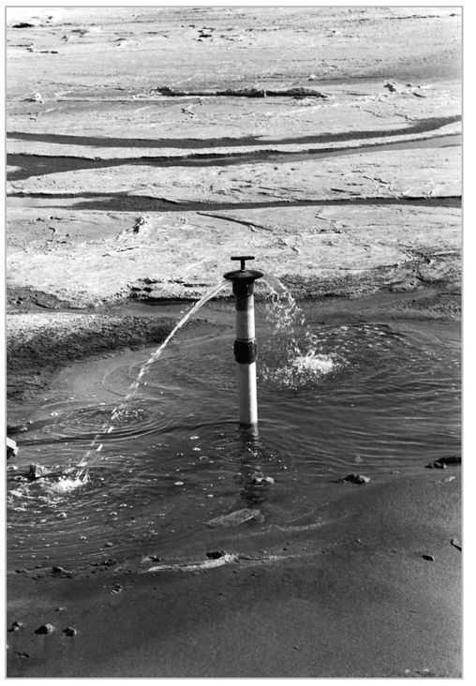

Los Angeles enthusiastically obeys legal mandate to environmentally mitigate Owens Lake, 2005.

Chapter 93

COACHELLA’S SHARE (1918-1948)

T

he Coachella Valley County Water District board spent years negotiating for its own allotment of Colorado River water. Had they become a part of the Imperial Irrigation District they would have had to assume a share of its large indebtedness.

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

And so in 1918, hearing of Imperial County’s attempts to fund an All-American Canal, Coachella forms her own water district. The Highline branch is due her, and she will get it.

In 1920, the Coachella Valley County Water District may be found in the Masonic Temple at Sixth and Cantaloupe. Is it then a secret society of fecundity? I never entered the Holy of Holies. But surely the water district’s high priests advanced the First Commandment:

“ Moisture Means Millions.”

In 1921, Coachella files suit against Los Angeles in hopes of preventing her from appropriating electric power from Coachella’s preserve, Boulder Dam.

In 1922, Coachella wires Phil Swing in Imperial County: WE CANNOT AND WILL NOT BE SET ASIDE WITHOUT RECEIVING JUST CONSIDERATION AND COMPENSATION FOR OUR EFFORTS . . .

In 1938, workmen start digging the Highline Canal. In 1949, first water arrives in Coachella.

Chapter 94

SUBDELINEATIONS: WATERSCAPES (1925-1950)

Only in our own day has California reached virile maturity full-armed for many a worthy conquest . . .

—Rockwell D. Hunt, A.M., Ph.D., California and Californians, Issued in Five Volumes (1926)

I

n 1936, one year after San Diego finishes her El Capitan Dam, a certain Major Wyman draws up his project report regarding control of the Los Angeles River. The great flood of 1938, which kills forty-nine people, makes his proposals all the more attractive.

The ineffective and dangerous practices of building mountain reservoirs and small, inexpensive check dams were also brought out,

notes the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in another attack on irrigation democracy.

At that point, the Los Angeles River has been about halfway altered.

Prior to 1935 the three basic stream patterns—Los Angeles River, San Gabriel River and Rio Honda, and Ballona Creek—draining the Los Angeles area followed meandering natural water courses.

By 1921 the lower Los Angeles River had already been, in a fine neologism,

realined.

Next, the channel between southern Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley got

improved.

So did Ballona Creek. Then it came time to build dams.

The Colorado River now gets similarly improved,

162

and not only for safety reasons. In 1927 the State Engineer calculates that

four-fifths of the local supplies on the Pacific slope of southern California, excluding Owens Valley, are now in use . . . In order that growth and expansion may continue, . . . the Pacific slope . . . will require three times the volume of water that can be obtained from nature’s allotment . . .

We’ll need

a continuous supply of fifteen hundred second feet

for greater Los Angeles alone. Thank God for the Colorado!

But a memorandum of 1929 caps California’s take of that watercourse at four million, four hundred thousand acre-feet per year. Poor San Diego gets lower priority than Imperial County, Palo Verde and Yuma,

where rights have been established by long usage.

Alas! But Phil Swing himself offers reassurance:

These technical priorities, however, are of little importance, since the total of all California contracts is admittedly well within our legal limit.

In short, it is simply needless to question the supply of water, at least up here in Northside.

In 1942, Imperial’s first and most fundamental line, the one between the two nations, receives visual ratification at last upon completion of the All-American Canal. The inevitable treaty of 1944 awards Southside the munificent allowance of one and a half million acre-feet per year. For an arithmetical understanding of this little adjustment, consider the following: During the month of April 1926, the Colorado’s total discharge at Yuma was 1,404,000 acre-feet, shared equally by Northside and Southside through the Alamo Canal. Before George Chaffey opened the headgate of the Imperial Canal in 1901, Mexico would have received all of that water. She then by the Andrade patent remained entitled to half of it (no matter that Harry Chandler’s enterprises drank most of that half). She will now be permitted to receive one-twelfth of it.

Well, isn’t even that too much to waste on foreigners? Los Angeles complains that each acre-foot gained by Mexico will lose us five Angelenos.

Here’s a long concrete facade of many tall narrow niches through which the whitewater spews; its concrete pillars and its tall narrow louvered slits remind me of Nazi architecture, particularly of the Reichsbank, but appearances can be deceiving; I’ll never say that I’m against it. Shall I tell you what it actually is?

Exterior view of Nevada wing of Hoover Dam power plant which supplies city with 65 percent of all power requirements.

Which city? Do you have to ask?

Giant transformers raise generated voltage to 287,500 for power transmission to Los Angeles, 266 miles distant, over three transmission lines of Department of Water and Power.

Not many years after the completion of Hoover Dam,

163

pearl oysters, shrimps and several species of fish have nearly disappeared from a number of their accustomed dwelling-places in the Gulf of Mexico. (No one has informed me just when the last Delta jaguar died out; perhaps that was long ago, before irrigation.) In 1940 an adventurer sails up the Colorado’s mouth and determines that

there is something back of the rumors that the Colorado is a changed stream since it has been paralyzed by the building of Boulder Dam.

To wit, he

sees an immense and apparently ever-widening desolation

of dead cottonwoods, osage oranges, willows, grasses.

The region had formerly been a marshland, saturated with fresh water.

To be sure, subdelineation’s bite can be temporarily undone, and in 1949 another observer of the Delta enjoys an experience right out of Mexican California:

Often we seemed to be going silently down long, lavender aisles where tens of thousands of the salt cedar trees in full bloom trailed their blossoms in the water.

But Progress—bless her!—pulls Mexican Imperial in a drier, saltier direction. And so we find the farmers of the Mexicali Valley drilling into their aquifer, which gets some replenishment thanks to seepage from the as yet unlined All-American Canal; by the century’s end, six hundred and fifty-eight wells will pump out eight or nine hundred thousand acre-feet of water each year, gaining them half again as much as what Northside had allowed her.