Imperial (95 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

But seepage can repair only so much, and Imperial’s bifurcation remains visible: While the irrigated zone of American Imperial most often equals immense emerald rectangles both flat and dense, the counterpart area of the Mexicali Valley is, for instance, sagging honeycolored hay bales,

METALES PROGRESO

, the smell of refried beans and then the smell of boiling sewage, a young couple walking along the grey wall, an empty plastic garbage bag rising in the wind and hovering high over the street, laundry hanging out of windows on littered hillsides. Could these two different landscapes have anything to do with underlying waterscapes?

The rest of Mexican Imperial is in very good shape, thank you. Tijuana finishes the Abelardo L. Rodríguez Dam in the middle of the thirties. Now she is taken care of forever; it is simply needless to question the supply of water. Tecate’s five hundred and sixty-six residents cannot drink much.

Our newsflash now takes you back across the line to report other good news: In 1930 we find an advertisement for IMPERIAL VALLEY “TRIPLE A” ARTESIAN WATER, with company branches in El Centro, Brawley, Thermal, Mexicali

164

and Yuma—twenty-five cents a bottle.

More than a decade later, Riverside can also draw on artesian wells here and there; they just need to be drilled deeper. Some say Riverside water is sweeter than the Colorado River’s, which may be one reason why in 1931, Riversiders vote four to one against joining the Los Angeles-centered octopus known as the Metropolitan Water District. Speaking of sweetness, it may be a sign of the times that in 1937 a U.S. Salinity laboratory is established at Riverside.

By 1941, sinking water tables have begun to alarm a few superbrains in Los Angeles who note

the imminent danger of infiltration of immense quantities of sea water into an area 475 miles square,

including the Santa Ana and Los Angeles rivers.

But why couldn’t Imperial, and Riverside if necessary, and Los Angeles and all southern California, go on fixing the problem indefinitely by flooding the fields with Colorado River water?

Chapter 95

THE LINE ITSELF (1927-1950)

This drift toward a warlike fatality has been facilitated by subsidiary consequences . . .

—Thorstein Veblen, 1915

A

lthough Imperial County Assessor’s Map 17-10 depicts the International Border Line

(public reserve 60 feet wide),

as yet the blank white maps on which the Salton Sea is sadly, foolishly subdelineated into numbered squares seem to remain almost of a piece with the international line.—Back in those days, said Hermenegildo Pérez Cervantes of Mexicali, referring to the 1920s, the American Immigration had a passport with the mother and all her kids. That was on one passport. So from very young I went to Calexico. I went with my mother. She took me often. It was very, very small over there, ooh, very little! Just on the other side of the border was a store owned by an American Japanese man named Kawakita. My mother bought jars of lard, canned goods, beans, sugar, salt, rice, sausages, clothes, all in thick paper bags with handles. You could buy most everything there . . .

And a rancher woman in Calexico once told me, speaking of a neighbor: Before they had a border there, his family farmed on the Mexican side without knowing it!

But the years bite deeper into Imperial’s former coherence, as revealed by the line at Tijuana in 1932:

Down its yellow slopes drops a gangling fence, a tall network of wires supported on spindles, quickly to disappear in the thickets of a willow-bottom . . .

And consider the instructive business failure of a Riversider named Bing Wong. In 1933, the year after Hetzel took that classic photograph of snow on Signal Mountain, Bing Wong opens his first restaurant. Some of his best customers come over from Mexicali. But then authority decrees that the border must close at midnight! In nine months he goes out of business.

In the 1940s, subdelineation gashes deeper still. I’ve already told you about the All-American Canal. Meanwhile, Southsiders’ prospects of venturing Northside decrease. A woman born near the beginning of that decade and raised close by Signal Mountain remembers: We were three hundred yards from the All-American Canal. I remember at two in the morning waking up from all the activity, all the Mexicans singing; or sometimes here came the Border Patrol, chasing those people with flashlights . . .

THE RAPIST-SAINT

Those people who get chased with flashlights, between then and now they come to define the border with ever increasing persistence. For Northsiders, the other side of the ditch continues to be a place of

yes.

As for inhabitants of Mexican Imperial, for them the line is an ever more bitterly reified exclusion. Hence the tale of Juan Soldado.

It happens in Tijuana. In 1938, an eight-year-old named Olga Comacho fails to come home. The little corpse shows evidence of rape. Juan Castillo Morales, aged twenty-four, possibly from Jalisco, is arrested; his clothes are bloodstained. His continued existence incites a riot. Accordingly, three days after the discovery of Olga’s body, the army, having tried him without undue ceremoniousness, conducts him to the cemetery, in some versions makes him dig his grave, then shoots him. On the following day, an unknown old lady lays a stone on the earth that covers him and invites us all to pray, whether to him or for him is unrecorded.

Those who pray

to

him claim that John the Soldier was framed by the real rapist, his commanding officer. Accordingly, he is said to help those who suffer persecution by such authority figures as the Border Patrol. To be sure, numerous ex-votos praise him for this successful medical operation and that fertile conception, although the following seems more à propos:

I give you infinite thanks, Juan Soldado, for having granted me the miracle of saving me from the big prison that awaited me.

Passport-sized photos of men adorn the chapel which now frames the site of his execution. People thank him for assistance with their immigration documents. He is especially beloved of

pollos, solos, bodies.

Why not? There must be kinship between the rapist-murderer and the unwanted Mexican who risks death for the privilege of picking Imperial Valley lettuce: the powers that be disdain them both . . .

In the one image purporting to be of him, he resembles a little boy in his private’s uniform, simultaneously jaunty, martial and wide-eyed as he stands facing us, with his pale hand on a round, draped little table which bears a statuette of Jesus on the Cross. He has crossed the line. We can never hope to know who he is.

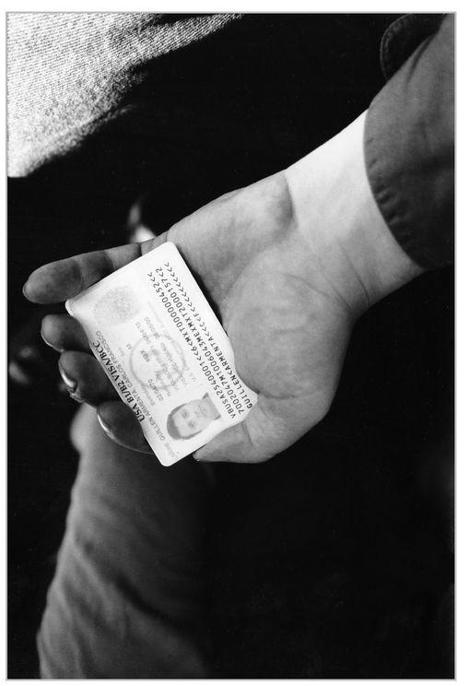

A limited-use visa for a Mexican national to visit the Northside, 2004

Chapter 96

DIFFERENT FROM ANYTHING I’D EVER KNOWN (1933-1950)

. . . they entered a world where the normal laws of the physical universe were suspended.

—J. G. Ballard, 1966

E

dith Karpen, born in Los Angeles, came of age just in time for the Depression.—And then I looked for a job, she said. And you know what teaching jobs were like then.

In 1933 I got a job offer in Calipatria. At that time, it was very, let’s say, I don’t want to say primitive, but a frontier-type town. It had two hotels, and if you went a block in one direction, you were out in the country. The other direction, you were out in a very small residential area. I lived at the hotel. It was the Hotel del Lingo. It was run by a widow, and periodically her sister would come to visit her, and she was the sister-in-law of Byrd the explorer. I don’t think she knew too much about his accomplishments, but it was interesting. I do remember at that time, I signed a contract for the school year for eight hundred and eighty-nine dollars, and I was thrilled to get that job, because in Los Angeles I had been working at the first Bullock accessory shop at twenty-five cents an hour. Anyhow, the school district found some extra money and I ended up with twelve hundred dollars. I was thrilled to death.

If you want to know my first impression, I was so lonesome when my parents brought me down there! I decided to go for a walk. I walked in the direction where the wilderness was, about two blocks, and there I heard this Mexican music, and they had a campfire and they had these workers around it, singing. I just stood out of sight and listened.

I was a curiosity, because the teachers there were mostly the wives of farmers, and it was during the Depression, so they weren’t about to give up their jobs. I always overheard them say,

There’s the new teacher!

Across from where I lived there was a drugstore with a soda fountain, and whenever I went in there, I was a celebrity.

To me it had a feeling as though it wasn’t part of California, because it was different from everything that I had ever known. For instance, they’d bring in a busload of kids, and then stop at the Fremont School to let off the American children and the Chinese children; I think they had only one Chinese then. Then they went to the Benita school, where I was teaching, and they let off the blacks and the Mexicans. Completely segregated. We had only a few blacks, I think about two families.

We had four rooms, and when the crops were in—we were largely a pea-picking area then—I’d have as many as sixty students, and then when they had a freeze or when the crops were in, I’d be down to about thirty or thirty-five, just overnight. They’d gone up to Salinas.

So these were the children of migrant workers?

That’s right. I had what would be called preschool. Pre-kindergarten, starting about five.

And were they American citizens, Mexican citizens, or all of the above?

I don’t think anybody ever cared.

Were there Mexican field workers who crossed the line routinely?

At that time, the growers would bring workers from the New River gorge.

How was the smell there in the thirties?

When I first got there, it wasn’t too bad. It got worse all the time. I had a friend who was very outspoken, and when I was there, he was lobbying, I would say, to build a dam, so that the water couldn’t come from Mexico!

How was your Spanish?

I was hired because I didn’t speak Spanish. Complete immersion! They called it Americanization.

So what would you do if a child had to go to the bathroom and couldn’t tell you?

They were pretty good with body language. I’ll tell you one story. I don’t know what they would think about this today, but shortly after I got there, we had gnats, and my kids were all getting pinkeye; they had this dirty muddy hair, and so when they came in from recess, I gave ’em all a Dutch haircut! They never talked back to me. You see, when I started at age twenty, I had to kind of lay down the law. The first Spanish words I learned were

amarillo

and

azul,

’cause I was blonde and blue-eyed. Sometimes they used to touch my hair.

What was your impression the first time you crossed the border?

My first impression was complete awe. Mexicali was really booming back then. They had cabarets. The Gambrinas . . . The big one, it was the Owl. We never, ever called it the Teclote; we called it the Owl! You would walk in, and here were all these gambling tables. I had led a very, very sheltered life, and you would go back and there was the gambling and the bar, and you would go back to the dining area, and it was real plush.

And how would you describe the El Centro of 1933?

El Centro on Saturday night was bustling, but the rest of the time was kind of sleepy. In El Centro they had the famous Barbara Worth Hotel. I stayed there once right after we were married.

165

It was very nice; it was always nice. Then the buyers for the grapefruit and peas and all, they would congregate, and a lot of business was done. There was a nice dining room. Jack used to take me there most Sundays. It was really top drawer.

Did you dress up for those Sunday dinners?

Oh, yes.

What did you wear?

I never went in for long dresses, just nice street dresses. In the summer I wore skirts and blouses . . .

And what was the rest of the valley like?

The north end of the valley and Niland was a hobo center, ’cause that’s where the trains switched. Then between Niland and the sea was the mud pots. There were different colors of mud, and it would go up and then go plop. They plopped up carbon dioxide, and a company came in and that was the origin of the Birds Eye frozen peas.

166

Where Slab City is now, that was good area for growing tomatoes. They like the sandy soil. But the desert was just desert. Ocotillos.

When I first came to the valley, she said, you’d still go part of the distance to Yuma on the plank road,

167

going out from Calexico, since the sand dunes were always shifting. Maybe seven miles of plank road were still left. It didn’t take very long; you’d just go slowly. Of course

everything

was slow then.