Imperial (92 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Mr. Campbell is, in one adversary’s words,

testifying against the Blythe group, and they constitute a group of seventeen shippers over there, nine of which ship in Imperial Valley.

He wants lettuce to continue to be speculative because

when you reduce your risk you invite more competition,

and what canny agribusinessman craves that? He worries further that a prorate

will allow men with bad lettuce to put it out and men with good lettuce to lose some of it.

At this, Mr. Kurht, the hearing officer, jumps in again: I think this testimony here that you have some sort of a voluntary prorate in effect is mighty dangerous for all of you, and I suggest that you just quit talking about it because you know that it is illegal . . .

What might be the difference between a prorate and a marketing order? In the latter course, the Department of Agriculture sets acreage limits. In the former case, which must be more in tune with the Imperial Idea, the growers do it themselves, without interference. That is also called

monopoly.

158

Never mind all that! Mr. John Norton, Jr., believes that

this marketing order is necessary to preserve a reasonable correlation between supply and demand for winter lettuce,

a sentiment seconded by that exemplar of Imperial, Mr. Dannenberg, whose unctuous words, so appropriately spoken in the Barbara Worth Hotel, reinvoke the sacred Ministry of Capital: Profit is not only sacred, it’s patriotic! To wit:

Collection

[

sic

]

action by farmers is as American as apple pie . . . We are finally going to vote on this in a democratic secret ballot . . . and I can’t help but feel that we are still all lucky regardless of which way this comes out, because you came here in a democratic fashion, as Americans, and I think we can all thank God that we still live in America.

Needless to say, the record reports applause.

Chapter 87

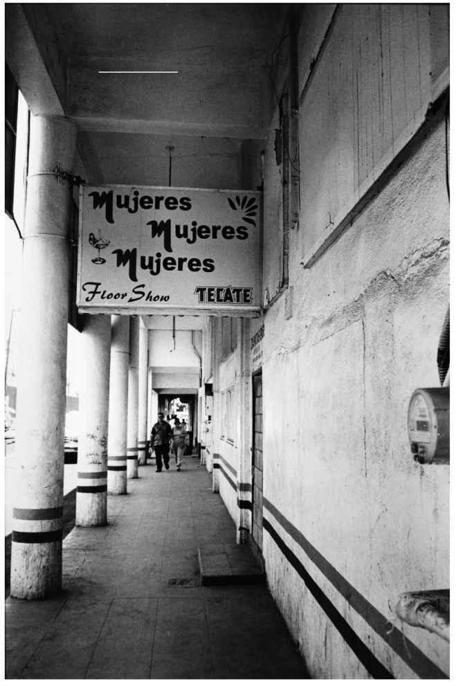

THE NIGHTS OF LUPE VÁSQUEZ

(2003)

. . . the highest honours within human reach may, even yet, be those gained by an unfolding of extraordinary predatory efficiency . . .

—Thorstein Veblen, 1899

Y

ou see that one with the big ass? God, she is beautiful! I want to dance with her and check her out. Usually it takes two dances or one drink to check them out, because not all of these girls are

putas,

you know. Some of them only want you to buy dances and drinks all night, spending your money for nothing. So I just say: Do you want to fuck? If no, that’s it. She’s fired. They appreciate that, because it saves their time. Where’s that one with the big ass? I can’t see her. Can you see her? Where is she?

Hola,

there she is! She’s dancing with someone else, the bitch!

Chapter 88

IMPERIAL REPRISE (1891-2003)

I

can’t help believing in people.

Did you ever consider them as machines—machines that make eggs?

And in material advantages they are already well supplied.

Why, I would be sick to my stomach if I rode down that valley in California, over those long miles owned by one man.

He sold out at a fancy price.

IMPERIAL COUNTY SHOWS RAPID INCREASE. The constant threat of heavy shipments . . . seemed to be the depressing factor.

I am willing to give a good deal of credit to the new methods of retail food stores.

Because of market conditions in 1934, the equivalent of 300,000 crates

of lettuce

were unharvested in the Imperial Valley.

She’s dancing with someone else, the bitch!

PART SEVEN

CONTRADICTIONS

Chapter 89

CREDIT WILL BE RESTORED (1929-1939)

“Credit will be restored and business will hum again—”

“When?”

“When Empire Valley wins a clear victory for the Boulder dam and the all-American canal. Then the bugaboos will disappear and prosperity will ride rampant.”

—Otis B. Tout, 1928

I

n 1929, many, many dark, squarish automobiles lie angle-parked alongside the multiple archways of Brawley’s main street, which is an almost textureless white in the sunstruck, timestruck photograph; I myself, coming to Brawley almost seven decades later, will never see so many cars parked there.

We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

American Imperial approaches her cusp. Mexican migration to the United States achieves a peak. More than fifty thousand railroad cars of produce pass clitterclattering out of the Imperial Valley every year!

He sold out at a fancy price.

Between 1919 and 1929, Imperial County moves up from forty-first to eleventh

in value of its agricultural production among all counties in the United States. In the past ten years, this county has made the greatest gain in value of its agricultural production of any county in the nation.

Imperial County is number one for lettuce, cantaloupes, melons, fresh vegetables! (Thank you, El Centro Chamber of Commerce.) In 1932, nearly three million unsold watermelons, a million and a half tons of unsold cantaloupes, and mountains of unsold tomatoes will be converted to waste, because if we once began to give our produce away to the hungry, wouldn’t every sly rascal pretend to be famished?

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

But in 1929 the future’s the merest black Rothkoscape whose darkness has no bearing on our emerald alfalfa-zones, our yellow-polka-dotted grapefruitscapes. Mr. Robert Hays announces:

The First Thirty Years of Imperial Valley’s existence far exceeded in accomplishment anything which the most hopeful of its valient

[

sic

]

pioneers ever dreamed of . . . My vision beholds the greater Imperial Valley of thirty years hence, then as now conceded the most productive agricultural area in the world.

Here comes Black Thursday and Black Tuesday; the stock market shrivels just as will cake-dough when you slam the oven door, but we don’t care; out here in Arid America we have better things to do than read about another Wall Street panic.

159

In 1930 the monetary value of Imperial County’s tangible property, at least as measured by the assessor’s office, reaches a summit of $6,257,231. Out go fifty-seven thousand, seven hundred and one carloads of Imperial Valley products!

SEARCHES MADE FOR DEFENDANTS IN ALL DIRECTORIES

Imperial is men with hats, men with beards, sitting half a dozen at once in a horse buggy whose huge wheels are half sunk in the dirt; Imperial is a photograph captioned

Calipatria 1927:

the American flag waves over the dirt.—But now the bad years are upon California. Here’s a photo from an album: hats on the table, bowed heads, men grim on courtroom benches, and a woman looking down as she writes. Men bend over paperwork. The title:

Sheriff’s sale of foreclosed farm.

The Imperial Valley directory for 1930 offers this advertisement as a sign of the times:

Attorneys, Attention!

Searches Made for Defendants in All Directories

Throughout the United States.

AFFIDAVITS FURNISHED.

Meanwhile, we’re also advised of the following:

Confidence in the continued growth of Imperial Valley’s wealth, industry and population . . . will be created as sections of this directory are consulted.

If only other Americans had consulted sections of this directory! Maybe then the year 1931 wouldn’t have been worse than 1930. Next up: 1932 and 1933.

Because of market conditions in 1934, the equivalent of 300,000 crates

of lettuce

were unharvested in the Imperial Valley.

In 1935 the national unemployment rate will remain steady at almost twenty-two percent.

As for farmworkers, Paul S. Taylor concludes:

. . . the Depression . . . altered the political terrain, by reversing the actual flow of Mexicans from an incoming tide to an outgoing tide of unemployed.

I’VE NEVER BEEN CHEATED OUT OF A DOLLAR IN MY LIFE

In a filing cabinet in the archives of the Imperial County Historical Society Pioneers Museum, a five-page typescript entitled “How It Feels to Be Broke at Sixty, or, High Finance in Imperial Valley” looks back upon its author’s career with a resentment aggrandized by typically Imperial rhetoric into a eulogy for a historical mission betrayed:

I could see our little family as we had come on to

[

the

]

desert, years before. Wife and I in the prime of life, willing to work and sacrifice, that the forces of nature might be controlled; the desert reclaimed; our children educated and a little accumulated, for our old age, and perhaps something to give our children a start . . .

I could see the desert boundless . . . a vast sea of rolling sand . . . while the sun’s rays danced and in the mirages

[

came

]

. . . buildings and ships and castles and mountains, creating scenes as awful as they were attractive.

I could see the sun as it appeared in the eastern horizon in the early morn, a big red ball of fire, the size or redness of which was never seen after vegetation began to grow . . . I could see the farm as it began to take shape and was being covered with cattle and hogs and barley and corn.

The farm must have been attractive; for Otis P. Tout informs us that

W. E. Wilsie’s new home two miles west of El Centro was the finest in the Valley.

The Wilsies were close neighbors to Wilber and Elizabeth Clark.

I could see my wife in her kitchen about her daily work,

Mr. Wilsie continues,

and the children as they became old enough, each taking their place, boys and girls on horseback, herding, in the milk yard, and in every way doing their share toward accomplishing the task that we had set out to do . . .

I could see the development of . . . the greatest enterprise of the kind the world has ever known . . .

In short,

THE DESERT DISAPPEARS

.

“Moisture Means Millions.”

WATER IS HERE

. Then what?

I saw our fine ranch divided and sold through a system of profiteering and high financing, as shameful as it was unjust. I saw our three boys volunteer and set off for the war without a tear, but with a hearty Godspeed from their loyal, heroic mother.

But the profiteers, he bitterly notes, didn’t send

their

boys.

I saw our fine ranch divided and sold.

But isn’t subdivision the name of the California game? In our introduction to the Inland Empire, the point was already made, and out of laziness I quote myself verbatim, that the history of Imperial, like that of California and the United States itself, may be summed up as follows:

(1) Exploration.

(2) Delineation.

(3) Subdivision.

By all means subdivide desert emptiness. For that matter, subdivide the Mexican land grants; those grand old delineations were made in the name of an obsolete alienness; Northside has taken over now! But when the Wilsie Ranch gets subdivided, please don’t expect W. E. Wilsie himself to call that procedure

the greatest enterprise of the kind the world has ever known.

Two points ought to be made about this sad document. The first is that it was written

long before

the Great Depression began. In fact, Mr. Wilsie lost his ranch during the war boom year 1916.

The second has to do with how the ranch was lost. Do you remember the direct gaze of that confident man, Barbara Worth’s father? Mr. Holt is said to have loaned Wilsie a few mule teams; when he tried to return them, Holt said he didn’t need them at the time. Later on, he presented his victim with a huge bill.

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.—

But another story simply runs that Holt had nothing to do with it: Wilsie had planted too much cotton.—Reader, are you a leftist or a rightist? Take your pick of causes.

We often tend to think of the Depression as a shockingly unique event. But the Wilsie Ranch’s epitaph for itself suggests otherwise. What are we to make of the characterization of Mr. Holt? After 1929’s Black Thursday, the Ministry of Capital temporarily lost its good name.

Since 1930, the most despised and detested group of men in the Union is the bankers . . .