Imperial (91 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Chapter 86

SUBDELINEATIONS: LETTUCESCAPES (1922-1975)

The main reason we cannot read these early texts is the fact that writing initially was nothing more than a means, more comprehensive than those employed before, of recording the details of economic transactions.

—Joan Aruz, 2003

W

hat might Imperial’s signature crop be? Doubtless the confident men of 1912, who coined the slogan

IMPERIAL VALLEY: Cotton Is King,

would have proposed cotton, and we will give it a short chapter later—but cotton proved to be one of Imperial’s many intermittent disappointments. Then what about sugar beets? According to Paul S. Taylor, it was the mechanized monoculture embodied by both cotton and sugar beets which brought Mexican migrant labor into being; but the history of the latter commodity in the Imperial Valley, delightfully soporific as our research might be, would need to account for the tragic fact that on occasion San Luis Obispo County, not Imperial, has grown the nation’s earliest sugar beets. Dates, oranges and grapefruits, my three personal favorites, are all frivolous choices and must be confined to subdelineations at best.

I therefore propose either lettuce or cantaloupes. The first of these is a safely ubiquitous staple; the second, as you may recall, originates early enough to be found in most pioneer histories of American Imperial. Moreover, both of these bring Imperial particular lucre in the winter months, being among the so-called early crops which make her

The Winter Garden of America.

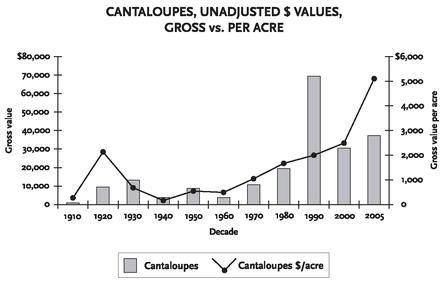

For cantaloupes that archive tiger Mr. Paul Foster furnishes the following chart and commentary:

A startling contrast to dairy,

Paul concludes.

This crop is the most obvious and consistent beneficiary of Imperial’s two clear advantages: a long growing season and a consistent and plentiful water supply . . . With only a couple of exceptions (most likely due to crop problems or worldwide depression), cantaloupes and honeydews have been a remarkably stable and profitable contributor to valley agriculture. As with several other crops, Imperial is typically the first US growing region to bring these melons to market in the late fall and early winter, and improvements in per acre productivity have helped keep this niche crop remarkably profitable. This crop is also aided by the fact that almost all of it is picked during the cooler seasons, with the result that it’s easier to find labor for the harvest.

Cantaloupes are utterly Imperial, all right. And I do wish to take this after-dinner occasion to celebrate the fortitude of men in the Brawley Cantaloupe Growers’ Association, who wear suits, ties and jackets for their group portrait in the heat of 1910. However, to quote from the historical record:

This is a lettuce hearing and we object to anything that relates to cantaloupes.

Hence the remainder of this chapter:

In 1922, the Horticultural Commissioner gleefully reports that

there were 12,000 acres planted to lettuce. The frost cut down the production but raised the price to unheard of profits.

In 1924, Imperial County ships out nine thousand four hundred and eighty-nine carloads, more than half of California’s total production. In 1925,

growers in the Imperial Valley are alarmed at the estimate of 30,000 acres of lettuce in the fall planting, fearing overproduction.

(Undeterred, Ed Miller ships out the first carload of lettuce ever from Blythe that year.)

Because of market conditions in 1934, the equivalent of 300,000 crates

of lettuce

were unharvested in the Imperial Valley.

Therefore,

155

in 1935, the Valley cuts its lettuce acreage to less than half.

Suddenly Arizona has become Imperial’s rival for winter lettuce! A quarter-century later, an Imperial lettuce man named Mr. Bunn will say:

. . . in the last few years Arizona has been stepping on our toes.

The two contestants grapple eternally.

The first trainload of Imperial Valley lettuce of the 1936 season departed on the third of December, 1935, and brought the impressive price of two dollars and twenty-five cents per crate. It arrived in New York city on the day after Christmas, there winning a wholesale price of three to three and a half dollars! But light demand, combined with heavy shipments from the arch-enemy Arizona, had already begun to press revenues downward. Almost a hundred traincars’ worth of our dollar-colored crop ended up unharvested in the Valley. By the third of January, the cash price was merely eighty to eighty-five cents a crate for Phoenix lettuce-heads; the Imperial crop did slightly better at ninety cents to a dollar. The California Board of Agriculture consoled us:

Distribution of the 1936 crop in Imperial Valley extended to 263 cities in 45 states, the District of Columbia, and Canada.

156

Two years later it was worse, not just in Imperial but all over California, and the Board of Agriculture had to admit that

in most branches the returns realized were most discouraging.

The Director went on to complain about the

lack of harmony and lack of support for a marketing order on canning cling peaches. Producers were able to realize only the cost of harvesting their crops, whereas under a marketing order in 1937 they received one of the highest prices paid peach growers in almost a decade.

What do you think caused those discouraging returns? After all, Imperial Valley enjoyed the vastest carrot crop ever, forty-three percent greater than the previous record, which had been set last year, and thanks to low competition, the growers did slightly better than break even. Cantaloupes likewise fulfilled the dreams of Imperial’s pioneers, and so it was an acrimonious cantaloupe season, marked by arguments over whether or not to plough under a third of the acreage to reduce supply. Lettuce prices remained steady in Los Angeles, but that did Imperial no good.

The 1938 lettuce season was probably the most disastrous in the history of the

Imperial Valley.

The quality was excellent, you’ll be happy to know, but the soil was just too damned good!

The constant threat of heavy shipments . . . seemed to be the depressing factor.

(Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1754:

I have seen men wicked enough to weep for sorrow at the prospect of a plentiful season; and the great and fatal fire of London, which cost so many unhappy persons their lives or their fortunes, made the fortunes of perhaps ten thousand others.

) After a lukewarm start at a dollar five to a dollar twenty-five, prices wilted to eighty-five cents to a dollar ten.

157

Almost all of the lettuce sold below cost.

In 1949, some of Imperial’s gamblers must leave the casino table, for thanks to a freeze and a general price decline the total cash valuation of the county’s crops decreases from the previous year’s, but

the lettuce deal, due to seasonal conditions, was the exception,

the County Agriculture Commissioner consoles us.

Markets were steady and F.O.B. prices were a near high record from January to April when the season closed.

Imperial is truly America’s winter garden. Lettuce revenues increase sixty percent from 1951 to 1952.

And in 1958, when market price is

a dollar and a quarter for the best,

at ten-o’-clock in the morning and not much more than a week before Christmas, a hearing on a proposed marketing order for winter lettuce comes to order in the Barbara Worth Hotel in El Centro.

WHO IS WHO

To set the scene, let us cast a quick eye all around the lettucescape.

This year Imperial Valley has shipped more than ninety percent of all American lettuce, and there is no reason not to refer glowingly, as does a certain Mr. Dannenberg, to

that particular period of time when Imperial Valley shipped three thousand two hundred and fifty-nine cars and the great state of Texas shipped six cars—

but the Valley’s victory endured only from 6 to 20 February. Since winter lettuce is harvested between 15 November and 31 March, the Valley, unfortunately for its boosters, cannot be said to control the winter lettuce market at all.

Blythe holds perhaps twenty percent of Imperial County’s lettuce acreage. The shipping season there runs from mid-November to mid-January, and then from late February until mid-April. So Blythe scarcely overlaps with the Valley.

The Valley wars with Blythe. Meanwhile, Yuma is the common enemy. Riverside and Los Angeles continue to be players.

THANKING GOD THAT WE ALL LIVE IN AMERICA

Among others, the above-mentioned Danny Dannenberg from El Centro is present; so is John Norton from Blythe (he owns land both at home and in Phoenix); Earl Nielsen of El Centro will rivet us all with his gnomic remarks, such as:

You may have too much lettuce which is not enough and not enough lettuce which is too much.

The legendary Lester (Bud) V. Antle of Phoenix has also put in an appearance.—Do you remember what Richard Brogan said about him? I was asking when the family farm stopped being, in Brogan’s words,

unrealistic

in Imperial, and he replied:

When lettuce became big here. When Bud Antle started making a million dollars off lettuce in a hundred days. The only people equivalent to that are the oil people.—

We are apprised that in 1956-57, Antle

owned and had interest in

four thousand six hundred and ninety-four acres in the Imperial Valley. In the following season his acreage had dipped by half (did he sell out at a fancy price?); now in 1958-59 it is rebounding slightly.

He says: Opponents have used in one of their arguments to smaller growers and smaller handlers of lettuce that some of us are trying to control the market.

Dannenberg asks him if

he

is trying to take control, which he denies.

Joe Martori of Phoenix, who admits that

well, I have an interest in lettuce, if that is what you mean, yes,

in California, in Phoenix but not in Yuma, and who also allows that

surely we right now are competitive with Imperial Valley and so is Yuma and so is the Gila,

feels that lettuce production dangerously exceeds demand.

Now, that is the situation as many of us see it in Arizona.

The Yuma Vegetable Shippers Association agrees with him.

Martori reiterates: Not only the production but the acreages are increasing all the time.

S. C. Arena from Phoenix says: If it keeps going like this I am going to go broke. He estimates the cost of cutting and marketing to be

up close to a dollar a carton just for packing lettuce.

The oracular Earl Nielsen, who lives two and a half miles south of El Centro, wants a marketing order for a production ceiling. He has made the Valley his home since 1937 and grown lettuce since 1942. This year he left his lettuce field unharvested. He speaks like a stock market trader:

Blythe and Imperial Valley can control the market today on a downward trend, but they cannot control the market today on an upward trend.

Mike Schultz of El Centro, acknowledging that over the last four years the Imperial Valley has shipped nearly three-fourths of America’s lettuce, explains that 1954-55 was Imperial’s last successful season. The following year was

disastrous,

thanks to the acreage increase; acreage increased again last year. This year he’s kept about five hundred acres in lettuce. It eventually comes out that Mr. Schultz has done quite well on this commodity, at which point he coyly remarks:

I think it is common knowledge that I shipped a portion of my acreage to a gentleman in this room, and I made a slight—I saw a glut in the market, or thought I did—I sold my crop at a slight profit, or a good portion of it—up to that point I had a loss.

The hearing officer then helpfully says: I must instruct the witness, however, that he isn’t required to reveal any confidential data.

Reginald Knox, an attorney who represents

a number of growers and producers,

asks Mr. Schultz: Now, do you contend that the figures that you gave us for the period February 6th to February 20th 1958 are representative of the entire season of 1957-58?

I don’t contend that at all, replies Mr. Schultz. I am just showing the period for which I am testifying.

Mr. Knox: You just wanted to show that during that particular period that the market was low.

Mr. Schultz: No audible answer.

Who are these gentlemen? Somehow they don’t strike me as family smallholders. What is going on here? Why would Mr. Schultz wish to hide his profits?

Perhaps the testimony of Richard Campbell, who’s been for fourteen years the manager for William B. Hubbard in El Centro

(and they have some operations in Arizona)

will supply a hint:

I think the record will show over the past ten or twenty years that there has been a steady increase both in the number of acres available in this area for lettuce and also the number of producers . . . And I think that the real problem in this thing has not been the fact that we have lost so darn much money, but it is the fact that we are making so much.