Imperial (93 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

In 1930, Henry L. Loud still hopefully advertises his real estate and insurance business from the Barbara Worth Hotel. Imperial County’s hundred and one fruit-packing and loading sheds, her nine icemaking plants, her two hundred and forty miles of paved highway and above all her twenty-five hundred miles of irrigation and drainage canals still pulse and struggle; she is young yet; her organism can still fight.

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

Chapter 90

MARKET PRICES (1919-1931)

Sometimes it seems that Fortune deliberately plays with us.

—Montaigne, before 1588

C

otton almost reached forty-four cents a pound on the New York Exchange in 1919. In 1931 the low was five cents.

This two-sentence tale goes far to explain the class warfare that exploded in all sectors of Imperial in the 1930s.

Chapter 91

IN A STILL MORE ADVANTAGEOUS POSITION (1928-1942)

Of all the western myths, it is the myth of the family farmer, for whom the dams were claimed to be built, that has taken the longest to vanish.

—Sandra S. Phillips, 1996

T

he Imperial Main Canal of 1901 was a hundred feet wide, which sounds awfully wide to me, but pretty soon it wasn’t wide enough.

The novel which this book struggles to write, called

Once Upon a Time in Imperial,

takes place back when Imperial’s canals were wider so that Imperial herself was lusher, bushier and more beautiful; as I persist in informing you, those days of the old photos were coming to an end. The good news is that everyone wanted them to, except for the Mexicans and the Colorado River Land Company.

In 1922 the Swing-Johnson bill was introduced. It passed in 1928.

You have already met Phil Swing. I should also introduce you to Mark Rose, “father of the All-American Canal,” also director of Holtville’s Imperial Irrigation District: youngish, a tight necktie and buttoned down collar, a tight-clenched mouth, baby cheeks; I would have picked him for a small-town reverend. Among its complaints against IID, the

Los Angeles Times

(in other words, the Colorado River Land Company) singles out

schemers or impractical dreamers of the Mark Rose type.

—But back to our hero:

Swing is energetic, popular and efficient; his ability being recognized by his fellow citizens who have made him secretary of his Masonic lodge.

That is a distinctly Imperial point of view. For entirely unknown reasons, the

Los Angeles Times

is less enthusiastic about him.

In 1920, the Imperial Irrigation District crosses the ditch to pay a call upon individuals ingenuously referred to as

the Mexican interests.

Their members, it seems, have been paying less for irrigation than Northside’s ranchers. Mr. Allison of the Colorado River Land Company expresses willingness to let Southside’s rents go up, which will lower American Imperial’s acre taxes; unfortunately, Señor Luis Romero, deputy of the Mexican government, will not concur. Still, Mr. Allison (who hails, by the way, from San Diego and the Imperial Valley) holds out hope that the Mexicans, if handled gently, can be brought around. He is well aware of the danger if they do not: They might be punished with

the All-American Canal and the denial of all Mexican rights,

meaning the very probable drying up of the Colorado River Land Company’s cottonscapes.

160

The canal’s proponents have, he well knows,

their own schemes, under the camouflage of looking after the valley’s interests.

Oh, Imperial and those wicked, wicked schemes of hers! In the drought year 1924, Phil Swing accuses the Colorado River Land Company of intending to irrigate its Mexican acres just as much as ever, while the good ranchers of Northside go thirsty. Immediately, the company dispatches a public letter to the Imperial Irrigation District, stating its happy acceptance of a fair pro rate cut in water deliveries. Indeed, such is the Chandler Syndicate’s civic-mindedness that it has declined to order a single drop for its alfalfa until everybody has enough. Don’t say they’re not good Americans down in Mexican Imperial!

Cut to 1925, when the Senate Committee on the Colorado River Basin meets in the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles—a place which you and I have already visited, reader; we know it’s even swankier than the Barbara Worth. The Honorable John I. Bacon, Mayor of San Diego, takes the floor to warn that the Colorado is silting up so much that in seventeen years it may back up and flood the Imperial Valley, which I suppose he worries about for sentimental reasons. We need an All-American Canal, no two ways about it!

E. F. Scattergood, Manager of the Bureau of Power and Light of the City of Los Angeles, sees the amount of electric power generated by the proposed Boulder Dam as comparable to that of Niagara Falls. He’s for it, no doubt.

Now for the statement of William Mulholland:

Unless there is a dam, and unless there is a high and capacious dam that will regulate the flow of the Colorado River, this city will not be justified in having a thing to do with it.

But the

Los Angeles Times

predicts that an All-American Canal will bankrupt seventy percent of the landowners in the Imperial Valley. I would predict that at this moment Mulholland and Harry Chandler are not friends.

On Mayday 1926, in a magnificent display of self-interest rightly understood, the Democrats of Imperial Valley join the Republicans in urging the President not to permit politics to further delay Swing-Johnson. The Associated Chambers of Commerce of Imperial Valley pass their own kindred resolution. Meanwhile, A. Giraudo sends the Hon. George E. Cryer the first crate of cantaloupes from his ranch in thanks for the latter’s labors on behalf of Swing-Johnson,

which when consummated will undoubtedly be the greatest feat in human history.

Well, isn’t he right? A quarter-century later, Shields Date Gardens in Indio will describe its charms to tourists as follows:

The All-American Canal on the eastern shoreline is the old-timer’s dream come true . . . A comfortable day’s outing. Again carry grapefruit.

Tuesday, May 4, 1926, page one:

ACTION IS ASKED ON BOULDER. Imperial County Supervisors Go On Record for Quick Action.

Friday, May 7, 1926, page one:

BOULDER DAM BILL AGAIN DELAYED BY MEXICO QUESTION

, that is, Mexican rights to Colorado River water.

The need for money is desperate. Your dollars are the only way we can continue the fight . . .

In October, the new movie version of “The Winning of Barbara Worth” premiers in Los Angeles, of all places, at a conference

to discuss the allocation of funds and distribution of water for reclamation projects.

Perhaps because of that, probably thanks to Los Angeles’s

exhibit boosting the Boulder Dam

at Brawley’s Imperial Valley Mid-winter Fair, very likely on account of

your dollars,

and certainly in spite of Arizona’s infamous filibuster of 1928, Swing-Johnson passes!

The Western Union telegram has been pinned to the flower-heaped table; a man in a necktie grins wide-mouthed, holding up one finger. Another man, plumper, who wears a tie and a white shirt, beams in front of an American flag. Lights have been strung across the scene, from a smoke tree to a pole. And in the foreground, the crowd gazes up at the grinners; most of them are men and they are holding their hats in their hands;

WATER IS HERE

.

That grizzled Imperial County farmer named Eugene Dahm told me with a shrug: I remember in 1934 there was a drought in the Southwest. There was so little water you could hardly get any in. The canal went fifty miles into Mexico but

they

were using water like there was no tomorrow; they didn’t care about the gringos!

(

They

must mostly have been the Colorado River Land Company.)

In 1937 we moved to the ranch, said a lady named Edith Karpen, who figures in several chapters of this book. It was out at Mount Signal, eight miles out from Calexico, right by what is now right by the Woodbine Drop of the All-American Canal. One of the first events I went to, Jack took me out to Holtville, and they had a big celebration there, and it was celebrating the passage of the Swing-Johnson thing. See, before that, the water left the Colorado and went through Mexico, and of course when

they

got through stealing it,

we

got some back. So this was to have it on the American side. So the whole valley celebrated. You have no idea of the

spontaneity

! Someone would mention Swing-Johnson and everybody would get happy!

So they took the south end of our ranch for the All-American Canal, and you know, I remember watching them. And they had mules that pulled these scrapers! That was the area in our section that was done by mule teams. A fella named Lee Little had the contract for that area. He lived out from Mexicali but he was an American citizen. It was a full section we had—six hundred and forty acres—before they started scooping away at it. Then it was about four hundred acres.

How did you feel about that?

We were happy.

She was happy, as were Swing, Johnson, America, Imperial & Co.! Early in the next century I find a social anthropologist looking back on this epoch and concluding that the All-American Canal was

from the very beginning

perfect, which is to say

an inappropriate answer to a misconceived problem.

Well, so what? We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

By 1931 El Centro’s official map already gloats:

When new lands are added through construction of the All-American Canal, under the Boulder Dam Project, there will be one million acres of the most fertile land in the world, with El Centro as its center.

161

The Mexicali Valley might become a trifle

less

fertile as a result, but that’s hardly Northside’s business. In 1939 the Chamber elaborates: Our million acres, now revised to eight hundred and fifty thousand, will comprise

about one-fifth of all the land in California under the plow.

On Christmas Eve of 1932 the first workmen begin to build a camp in Fargo Canyon,

signaling the beginning of work on the Metropolitan Water District aqueduct through the Coachella Valley.

And in the old map books from the Imperial County Assessor’s office, I’ve seen a page from that very year, a hand-drawn bird’s-eye snapshot of moneyscapes which sports a blackish fissure labeled in pencil

All American Canal—Coachella Branch.

In 1934 Indio calls an “Aqueduct Miners’ Day.” That’s the year I see Evan T. Hewes, President of the Imperial Irrigation District, at his desk, smiling, pretending to be about to write something, his fat pen poised above a document . . .

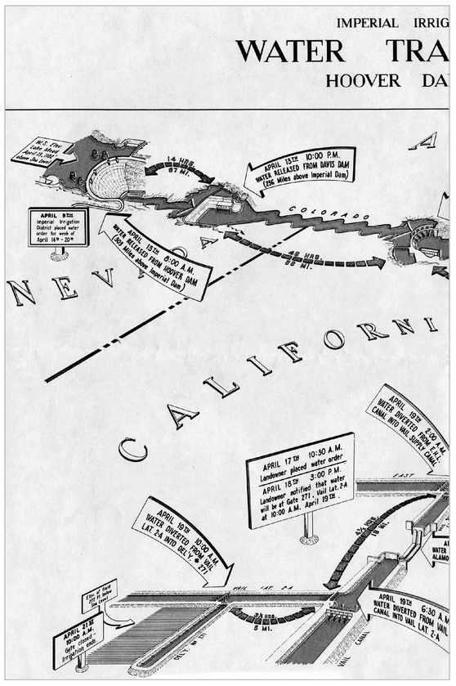

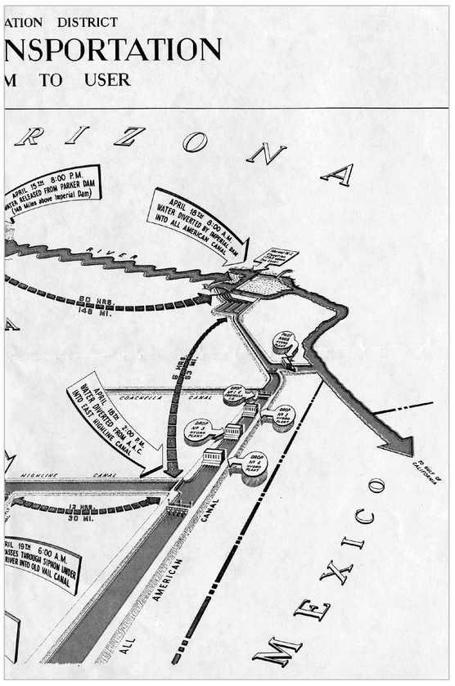

In 1940, first water comes through the All-American Canal. By 1942, the old Imperial Main Canal is dry.

PHOTOGRAPHS OF HEAVEN

I see still water on the very edge of the sky, reflecting blocky concrete towers with concrete arches between them, and a massive cylindrical assemblage boring through everything. The desert hills are low and distinct behind them, like the edge of the world. All is still; all is clean. These are the dam gates of the All-American Canal, and they double themselves upside down in the pool of liquid capital in Horace Bristol’s photograph of 1941. An aqueduct S-curves through the mountains for eighty miles, two hundred and thirty-two feet wide, filled high and clean with water that foams and ripples through the scrubby desertscape. We’ve conquered Nature.

Workmen stand mostly facing outwards on the upper level of a cylindrical concrete tower whose flat floor of timbers holds workbenches galore and whose inner wall is spiderwebbed with dark rods or cables which remind me of the jointed metal legs behind typewriter keys; this Bureau of Reclamation photo, dated October 1951, is stamped

BOULDER CANYON PROJECT

and

BOULDER CITY, NEVADA

.

We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.