Imperial (89 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

One (1) roan horse, 4 yrs. old, weight 1400 lbs. branded (AL) on left shoulder

and a black horse, a black mare, a bay horse, two sets of double harnesses, a cow and a calf, a wagon, three ploughs,

the entire crop of corn, consisting of about twenty acres and the entire crop of cotton consisting of about forty acres,

etcetera, etcetera, all of which

shall be kept and cared for on Larson Ranch,

since they no longer belong to Larson and Brumbelow, at least until they have been redeemed for three hundred dollars in gold coin, which is to say less than half the going rate of a Buick touring car, the collateral on the very next chattel mortgage in the County Recorder’s book. Three hundred dollars, yes—oh, and that ten percent. If Larson and Brumbelow default, why, the Farmers and Merchants Bank

may take possession of said property, using all necessary force to do so.

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

This time Larson squeaks by; he must have even succeeded in paying off Brumbelow (who like the other people in this chapter fails to appear in Otis P. Tout’s celestial index); for in 1925, a Deed of Trust on essentially these same mortgaged acres is conveyed to Albert and Elizabeth Larson, who will manage to avoid taking out any new chattel mortgages. Mindful of the impending suicide, I wonder whether the formalization of this transaction implies anything about the closeness of man and wife: They appeared on different days before different notaries.

In the same year, 1925, the Senate Committee on the Colorado River Basin issues its report, into the second of whose two hardbound volumes the Colorado River Control Club, which opposes digging any All American Canal but could live with a dam, submits a memorandum. Among its members we find two names:

Larson, Albert H, 76.62 acres valued at $3,740.00

Larson, Elizabeth, 90 acres valued at $2,000.00

153

(Wilber Clark’s name is absent.)

Perhaps the Larsons believed their irrigation assessment to be already high enough. But how could they trust that Colorado or New River floods had finally been taken care of? On Imperial County Assessor’s Map 12-12, where Westmorland Union meets Westmorland, the New River squiggles toward the Salton Sea, then suddenly and finally makes two inhumanly straight bends labeled NEW RIVER CUT 1924. Perhaps that was good enough for Albert Henry Larson. In 1926, however, another levee would break, flooding bits and pieces of Mexicali once more, and—one would think—endangering any property in Imperial, r 6 mi NW. So life would and must go, until the Colorado got utterly

smoothed out.

Had Larson invested in the Chandler Syndicate’s Mexican lands?

That

contingent did not support the All American Canal, which would render their water rights worthless. I have not succeeded in finding any roster of Harry Chandler’s stockholders, so I cannot tell you. Larson’s motivation in opposing the canal, like his other thoughts and drives, will never be revealed to me.

I keep wondering whether his suicide had anything to do with

the spirit of the

Imperial Valley.

In this period the U.S. Department of Agriculture expresses worry about the way the development and agriculture land, which used to result from individual will, now takes place

under the guidance of private agencies engaged in promoting the settlement and sale of land for profit.

Mr. Holt’s various syndicates, and the California Land and Water Company in Los Angeles (which shows such kind care for Brawley’s future), not to mention the Colorado River Land Company, do any of these fit the bill of accusation?

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

The USDA continues:

. . . numerous agencies, whose volume of business is very great, are preying on the impulse to buy farm land . . .

The USDA laments

the results in misdirected investment of capital, futile labor through years of unavailing struggle against hopeless odds, and consequent discouragement . . .

What wore Larson down? Was Elizabeth about to leave him, or was it business that destroyed him, or was he ill?

On the day of Larson’s autopsy, Jack Armstrong is selling forty acres for three hundred dollars, half of which is

under ditch and easy to level.

WATER IS HERE

.

We need to have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

Meanwhile, Armand Jessup has two addresses, one in San Diego, the other in Seeley; he has a hundred acres of ditched and leveled land for sale, rent or trade; evidently any arrangement would be better than the one he has. Is he an Imperial sellout or a San Diego speculator? On the thirtieth of April, a notice informs us that H. L. Boone is holding a closing out sale on all his horses, his twenty cows, his mules, his trucks and even his slop cans, with six tons of head corn thrown in.

NOTE—Mr. Boone has leased his ranch and everything goes.

It’s just another die-off. It’s natural. I guess we all feel sorry for ’em.

(That last sentence, expressed, as you may remember, by Border Patrolwoman Gloria I. Chavez, referred to illegal aliens. Officer Dan Murray on a related subject:

They do work Americans wouldn’t do.

And on this hot California day, as I meditate on the long death of Albert Henry Larson, I wonder whether Mexican ranchers and

ejidatarios,

given the land and crops that Larson possessed, would have failed as he did. Who was he? Again I ask, and again, why did he kill himself? Had he reached

the results in misdirected investment of capital,

in other words unlucky speculation, or did he take up gun and razor after

futile labor through years of unavailing struggle against hopeless odds, and consequent discouragement?

In either case, what might the defeats of all these Anglo farmers say about the Imperial idea?—Probably nothing. Most Imperialites don’t kill themselves.—And never mind the

unavailing struggle against hopeless odds, and consequent discouragement

that a Mexican field worker may or may not face in the Imperial Valley while he sells his youth and strength for piecework; after all,

they do work Americans wouldn’t do.

Why did this become the rule? Can field workers perform any tasks that Wilber Clark and Albert Henry Larson would have declined? When are homesteaders succeeded by growers?)

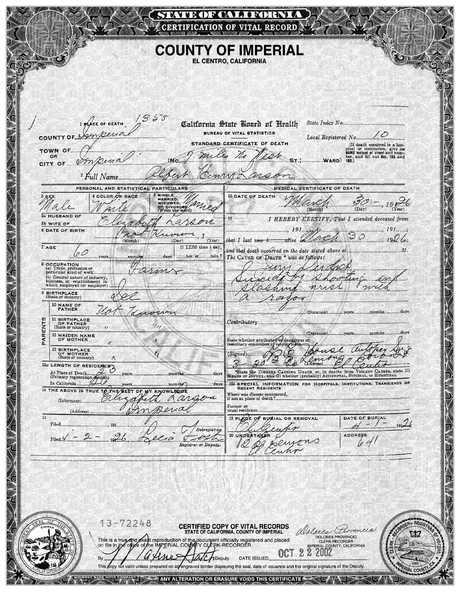

Now Larson’s listed domicile has become Rural Route 1, Box 37, Calexico, but the address on the death certificate,

7 Miles No. West

of Imperial city, renders his sojourn in Calexico all the more provisional. Was he trying one last business venture, perhaps something to do with Southside, before finally returning to stare down death at Wideawake? Meanwhile he buys another lot near the Larson Ranch.

Less than two weeks before his suicide, Larson proceeds to the County Recorder’s office and makes an official declaration of homestead. The listed acres are, as usual,

7 Miles No. West

of Imperial.

THE BACKBONE OF THE NATION

Larson would have been born at the end of the Civil War—out of California, I presume. (Seventeen Larsons are listed in the 1870 California census, from Andrew to Peter S., all white males, one from Los Angeles, one from Copperopolis. There are also nineteen Larsens. None is our man.) When he came into Imperial he would have been thirty-seven or thereabouts. He had slightly more than a third of his life left to live.

Life, and especially Imperial life, is a narrow, precarious thoroughfare in the midst of arid death, like the dark double tier of the old plank road, winding across the sand dunes, with Signal Mountain on the horizon; that used to be Route 80.

He got no obituary in the

Imperial Valley Press,

but shortly before Larson’s suicide, a French economist wrote:

The industrial wealth of the United States must not deceive us. Agriculture is still the greatest American industry. That is why the farmer is the prime element, one might say the backbone of the nation.

So now we know what he was.

No, he lacked an obituary, although I did come across an ad for Rin Tin Tin, starring in “The Night Cry,” and on Thursday, May 6, the following was reported:

MRS. LEROY HOLT HOSTESS AT TWO PRETTY AFFAIRS.

Life goes on, doesn’t it? Fred Nebel Than has already set off

for eastern points to boost the sales of cantaloupes throughout the country;

last year he did the same for lettuce. On the day that Mrs. Holt’s pretty affairs astonish the world, the first trainlot of cantaloupes rolls out of El Centro; and Southern Pacific brings twenty thousand refrigerator cars to bear for the biggest cantaloupe season in history.

Reader, do you want to know what a real Imperial image looks like? Here we go: A year after Larson took up gun and razor, we find five girls in knee-length skirts posing amidst the produce crates of Jack Brothers and McBurney Co., known for their GOLDEN QUALITY brand. The photograph is captioned Brawley, California. The two young ladies in front are holding bristling fans of many gleaming carrots; the rightmost and leftmost in the back hold melons, and the middle one, the straightest, properest girl, whose black bangs have been cropped perfectly even and whose stockinged legs are welded politely together beneath the dark skirt, cradles on her lap a monstrous ball of kale or spinach. This must be

the spirit of the Imperial Valley.

And I somehow still believe that if I were to prowl round and round this epoch as I did the Chinesca, I would finally discover some tunnel into the Imperial’s underside where Larson’s death has left us messages in a rat-gnawed desk.

LAVENDER

Larson is gone. We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by. In the old cemetery on the outskirts of Imperial I see Greenleaf, Ingram, Wood. I cannot find any Larsons. Albert Henry Larson, as it happened, was autopsied and buried in El Centro. In keeping with the apodictic certainty of those days that Imperial would soon be a citrus paradise, the name of his undertaker, who doubled as coroner, was B. E. Lemons. They interred him on April Fool’s Day. What about Elizabeth? Where might she reside nowadays? Well, there are many almost obliterated inscriptions on the flat reddish earth. By 1929 she had sold all her acres and his. Greenleaf, Ingram, Wood . . . Markers are missing. It is very flat and empty, hot and dreary. A nearby lavender field is singing out perfume at a hundred and sixteen degrees.

Chapter 83

SUBDELINEATIONS: SCROLLSCAPES (1611-2004)

I

mperial is ink on decorated paper. Imperial is the poetry anthology

Waka Roei Shu,

inscribed by Asuka Mosaki (1611-79). Imperial is, in short, a scroll of a fabulous landscape, gold on white: gold palmlike trees, gold rice dikes which might as well be lettuce fields, gold clouds. Imperial’s wide landscape unrolls in either direction, potentially forever, dusty and hazy and sunny.

The

Waka Roei Shu

is but one of many treasures at the Tokyo National Museum. It is but one of Imperial’s myriad scrollscapes.

Once upon a time at twilight, a dusty wind began to rise in Mexicali. It soon became a rainless storm whose cold flurries of dust attacked our eyeballs, ears, nostrils, teeth and throats; our hats blew off; we had to squint almost to blindness. People ducked their heads; awnings were shaking; and that taste of Imperial dust saturated our mouths, not unpleasantly. With stinging eyes we watched signboards blow over. By eight the dust had mostly fallen wherever it was going to fall on that occasion, and there remained merely a cold wind, depositing the occasional mote in our eyes to remind us of ourselves. That wind smelled of Imperial, which smells of dust. The prostitutes in the Hotel Nuevo Pacífico sheltered behind their glass doors; the prostitutes at the Hotel 16 de Septiembre withdrew far up their steep warm stairway, some of them reading as they sat on the stairs because who was going to visit them on a night like this? Besides, if anyone did come, they’d know it when he poked his head in. At the Hotel Altamirano I saw only one whore, who stood in the doorway a single step back from the sidewalk just as usual; she must have been tougher or more desperate than the others. She blew a half-smile my way, and my penis became as stiff as laundry which has been washed in Mexicali tapwater. At the taco stand outside the Playboy Club, the various bowls of guacamole, salsa, beans and chopped cabbage had been covered with plastic wrap, with a plastic spoon wiggling around in each dedicated hole. A customer’s used plate blew off into the sky, and the taco man cursed.

It’s progressing along real nice, the marina manager at Desert Shores had said in reference to the Salton Sea. And Imperial’s night was progressing as nicely as a white plastic bag puffing and whirling down Avenida Juárez, white against black in meaningless semblance of a struggle; the stars shone patiently above it all once more, reminding me, no matter how cold I might have accidentally felt, of holes in Imperial’s black roof, holes discovered and invaded by the glaring sun. After all, aren’t stars suns? And the wind blew, and a cat hid beneath an angle-parked car in front of the Hotel Chinesca. An old lady made a special detour across the street in order to request money from me. I gave her two pesos.—

Magnífico,

she said calmly. Then two girls with long naked legs and big bottoms went giggling by, their hair lashing each other’s faces, and the sidewalk fell silent; the archways dwindled down beneath their occasional incandescent tubes and reached their finish line, the barber pole, against which a bundled-up figure crouched, silhouetted almost hellishly; that was the whore who’d threatened to wait outside for me; she also wished to become a serial killer. In fact I’d looked for her a half-hour earlier—too bad she’d been off on business. Later I brought consolation money, arriving just in time to see her pinching her fifteen-year-old daughter, whom she was trying to sell; I couldn’t be certain that the selling was wrong, but I disliked the pinching, so I walked quietly on around the corner to watch another awning blow over. A cowboy wandered across the street, swaying in the wind, and came to haven at the Restaurante No. 8 (Comida China). And so many more things happened that night that it would take a hundred nights to tell you; and next morning, going south on the highway toward San Felipe, I came to the grand ballroom and café El 13 Viejo, where I found the manager on a scaffold refastening the tarps which comprised its walls; the wind had come this far and farther; it had been infinite.