Imperial (85 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

What did Mexicali look like in 1969?

Small town, very hot, very seldom a place that has air-conditioning, so that makes it hotter yet, roads not much paved, people were poor. You could hardly see much of high end, class people.

148

It was pretty much of a structure of a triangle: eighty percent poor and maybe ten percent rich, and not much medium classes.

So what was it like for you when you first arrived in Mexicali?

Oh, boy, I was nineteen years old; I was happy with my new toy, my power, my checking account, definitely! I thought it was a good opportunity for my goals. It was a poor city but could give me a lot of opportunity if I took my chances. It was not a nice place to live in, but it would give me an opportunity.

Is it a nice place now?

No.

Why?

When I was young I always had a lot of faith in Mexican society, but after twenty years or thirty years, I’ve been living with Mexicans, the lack of discipline in the family, in the behavior of the society, in the way they plan things, is a disappointment to me. They don’t have much conscience; they expect in everything help from the government; they’re not willing to sacrifice. After twenty or thirty years you still have the same problems that were here before and they’re still not able to solve them, and educational-wise, the Mexican is losing his effectiveness more and more. You don’t see much improvement, let’s put it that way. You do see people that have improved their life in Calexico.

The Mexicali Chinese often seemed to speak in this strain, from the Chinese Couple at Condominios Montealbán, who’d remarked to Clare and Rosalyn Ng that

it is not too hard to make a living and just get by in Mexicali, but if you are not satisfied with merely getting by, then it is a lot harder to make a good living for yourself and your family,

to Mr. Auyón, who told the Ngs that economic success in Mexicali was farther out of reach of new Chinese immigrants than it had been for previous generations. Mr. Auyón’s niece and her mother said that they were happy in Mexicali. They were the only people of Chinese extraction who said that. The Chinese tunnels would seem to be a good metaphor for the racial antipathies so frequently denied and so near at hand beneath the surface of the city.

Clare Ng came to see me in my house once, with some Chinese food which she had made herself. We were chatting about this and that when all of a sudden she said to me: I have kinda mixed feelings about looking at Mexicali, after I was there. Why did those innocent people come there? To have a better life. But actually they didn’t have a better life. Must be some people cheat them, to tell them they must have a better life. And it was their own people! Think about those people, eighty years ago! In the tunnel, living underground! And so hot! I don’t know. I tried to tell myself, it was their choice. But actually they didn’t have a choice. Eighty years ago, they couldn’t have a choice. Eighty years ago, the Chinese government was very poor. And the men who come here, they cannot bring the wife. Go every four years, make the baby, then go back. What kind of life it is?

Tim? What kind of life it is? He is fifteen, my daughter is seventeen, and when he see us he is so happy. He never open the door to the stranger. He doesn’t have life over there. I think the father came first. As long as you have money it’s not difficult to get the paper. All the same, Tim said when he got here he was so surprised. Life was completely different from the way the people told him. He was really disappointed. He just stay at home watching the Chinese nonsense television. He say he go to school but I don’t believe he improve his Spanish much. He’s working part-time at the Chinese restaurant.

It’s really nice, that new restaurant. The owner has been here thirty-five years, so he can make money. It’s very nice decoration inside, more nice than here in Sacramento. He said, even though China is more open now, the kids they don’t want to go back there. Some of them even marry with the Mexican. They just stay there, making money, go to China maybe once a year. He say he go to California maybe once a week, come to enjoy the life in San Diego Chinatown. He can afford it, but the other people, I hear they can live there for five years, they can come to America; they live there in Mexico for ten years, they can become an American citizen, but that’s a long hard time. I talk with one waitress in a different Chinese restaurant, and she was only there for six months. She think she can go to Mexico but can change the visa and go to America pretty soon. After that, she find out it take her five years. She is young, she is unmarried; what kind of people gonna marry her? Those Mexicans, all the woman working like crazy, and some store they don’t even have air-conditioning, and the men just fooling around. When we start going away, she look like she gonna cry . . .

Chapter 74

INDIO (1925)

I

ndio will soon have a seventy-two-room hotel, at a cost of seventy thousand dollars. We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

Chapter 75

THE INLAND EMPIRE (1925)

The citrus industry remained unchallenged as the major source of income and the identifying badge of the community.

—Tom Patterson, 1971

R

iverside, city and county—how are those two entities holding their own in the great race? Tetley’s Nurseries on Main Street in Riverside advertises itself as “Largest Citrus Nursery in California,” which sounds awfully unbeatable. From the streets of Upland we continue to admire the snow on Mounts Cucamonga and Ontario; no cars are parked in front of the Ontario-Cucamonga Fruit Exchange today

(ORANGES—LEMONS),

but three Fords prepare to

Serve the Surface with

BRADLEY’S PAINT

. Meanwhile, in Pomona, we can motor down Second Street from Locust, and receive Imperial inspiration from the sign which says:

PIGGLY WIGGLY

All Over the World

.

Riverside County performs “Ramona” thrice, with a cast of a hundred. Pity the heroine and her troupe of doomed Indians; we’ll applaud at the end when she moves to Old Mexico. And now Hollywood comes to Ontario and shoots films right here on Euclid Avenue!

In 1905 I gave you a photoportrait of

The World Famous Magnolia Avenue, Riverside,

with its towering dark trees lining an empty dirt road, and bushes on either side. Can you imagine how grand Magnolia Avenue has become now? Since 1913, Pacific Electric has been running trolleys there, fondly hoping that we will soon be able to travel by electric car all the way to Long Beach. Look upon my works, ye mighty, and despair.

In 1906, Riverside had controlled an irrigated area of a mere thirteen thousand acres. By 1921 she is prepared to introduce herself as

A city of American homes, institutions and ideals. A city of opportunity, especially for those seeking ideal farms and fruit lands.

Here are some of her inhabitants in 1921:

Alta Cresta Groves

Mrs. Mary E Rumsey prop S end of Maude

Altona Chas H

auto trimmer

Ames Geo T (Blanche)

fruit buyer . . .

Ammerman Moses A (Hannah)

rancher h 13 McKenzie

Hungate Zack (May)

rancher h 295 Kansas Ave

Hunter Wm J (Eleanor)

orange grower h RustonRD2 Riverside

(We also find the

Imperial Valley Investment Co

771 W 8th. )

In 1924 the first motel opens on Magnolia Avenue; in 1925, the Ku Klux Klan commences operations in our city of American ideals. Chinatown is already fading anyhow; and Chinese of both sexes have begun wearing Occidental clothing. In the thirties the Klan will threaten a certain George Wong, and he will chase them off with a shotgun.

He made a success through his own efforts.

In 1929, Riverside holds sixteen thousand orange-grove acres within her city limits! Palm Springs possesses trees, too—palm trees. Forty-seven Agua Caliente Indians still live there. In between dry spells, clear water flows amidst the pale slanting rock shelves of Palm Canyon.

Chapter 76

LOS ANGELES (1925)

It is a clean city—a good town. Its skirts have always been kept clean. The grafter and the looter have never been able to exploit it.

—John Steven McGroarty, 1923

CAPITAL’S ALTAR

Between 1900 and 1920, the population of Los Angeles grows fivefold. Her thirst enlarges comparably. As late as 1921, some of the city’s drinking water derives from the Crystal Springs wells, which lie either one or three miles downstream, depending on whom we ask, from the new Burbank Sewer Farm. Don’t worry; that funny taste is temporary.

The Los Angeles aqueduct will carry ten times as much water as all the famous aqueducts of Rome combined.

And in 1913, William Mulholland, who recently received a grateful acknowledgment in

The Winning of Barbara Worth,

pulls the lanyard that unfurls the flag that gives the signal that turns the wheel that opens the sluice gates of that aqueduct. I can’t help believing in people.

Only water was needed to make this region a rich and productive empire, and now we have it. This rude platform is an altar, and on it we are consecrating this water supply . . .

Hurrah! San Fernando explodes into citrusscapes!

By the way, do you remember the Chandler Syndicate? The Mexicali Valley is but one of their zones of interest. In 1924, we find Harry Chandler planning to superimpose a grid of automotive thoroughfares upon Los Angeles. He had prudently optioned fifty thousand acres of San Fernando before less wide awake citizens realized that Mulholland’s aqueduct would raise property values up there. I’ve never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

Between 1923 and 1925, more than a hundred thousand acres of Los Angeles get subdelineated into

city and suburban lots.

We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by. In 1927 Upton Sinclair praises such

subdivisions with no “restrictions”—that is, you might build any kind of house you pleased, and rent it to people of any race or color; which meant an ugly slum, spreading like a great sore, with shanties of tin and tar-paper and unpainted boards.

But for home-hungry migrants born too late to be pioneer homesteaders, these new tracts look prettier. Of course, even now irrigated or waterless acres remain for sale in Imperial (flavors: irrigated or waterless). But not everybody likes the heat. Besides, the Ministry of Capital is now drilling in Los Angeles, and I’ll make more money leasing out the gusher of “black gold” in my backyard than I ever could growing cantaloupes! Gardena and Lomita, Huntington Park and Torrance, even Signal Hill, all sprout oilscapes! White clots of smoke soften the bases of tapering black skeleton-towers. Cylindrical tanks shine and shimmer. In 1923, Los Angeles becomes the biggest oil exporter on the globe.

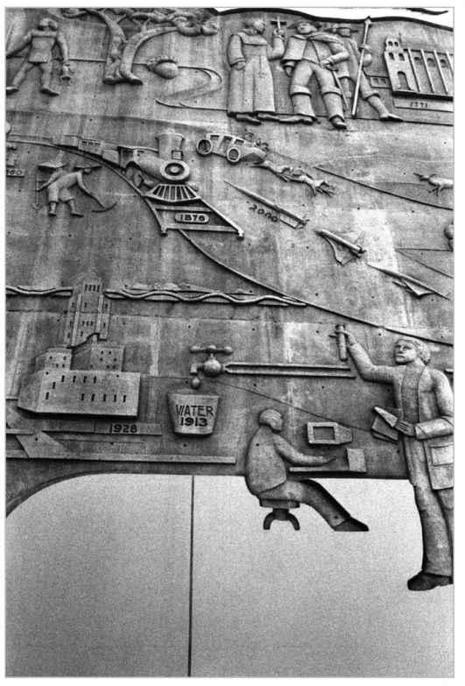

Los Angeles celebrates Mulholland’s aqueduct in a bas-relief.

The city hovers disheveled between farms and factories, between manure and concrete. On one single map from the real estate atlas of 1910 we see the Barber Asphalt Paving Company, L.A. Pressed Brick, the Puente Oil Company, and Southern Refining Companies A and B, all sprawling across the Sepulveda Vinyard [

sic

] Th., bisected by the Southern Pacific tracks shooting down Alhambra Ave. And so Los Angeles’s potentialities have grown as elongated as those Art Deco figures in the Biltmore Hotel: nymphs with breasts and crests, angel-devils as stretched out as the future’s limousines. In the Los Angeles of 1925, blue-collar surburbanites keep chicken-hutches in their front yards while oil derricks tower behind them; higher up the ladder of moneyed worth, a professional man can still be both an osteopath and a citrus grower.

RABBITS IN CHEAP JEWELRY

Speaking of giganticism, a California history from this period proudly explains that Los Angeles

is sometimes referred to as “earth’s biggest city”; and some men of vision

predict that in the future this might even mean something. Now for the dark side: Swiveling its considered judgments upon the barrios of East Los Angeles, the

Saturday Evening Post

concludes that their brownskinned inhabitants have brought

countless numbers of American citizens into the world with the reckless prodigality of rabbits.

This admiration of Southsiders and their descendants may not be confined solely to the

Post.

One-third of Los Angeles employers regard Mexican women as poor workers: unreliable, slow, unintelligent. By some peculiar coincidence, they earn less than females of other ethnic groups,

149

evidently since most

were from the lower class—

which is to say

predominantly Indian.

Our researcher finds them concentrated in the canneries, laundries and clothing trades; in the citrus industry they tend to be packers, not sorters, since the latter work is more skilled. Three-fourths are between ages sixteen and twenty-three; nine-tenths are unmarried. (Nowadays the

maquiladoras

in Tijuana and Mexicali also like to use young unmarried women, and doubtless for the same reasons.) Their homes tend to be cleaner than those of Mexicanas who have not entered the workforce: The windows sport curtains; sometimes they even own a radio. But their luxury knows limits: Although Southern California Edison has recently commenced advertising

refrigeration without ice,

I see no indication that they own the new gadgets called

refrigerators.