Imperial (120 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Manufacturing is hitting another level of evolution,

explains the President of Prince Industries. So outsource to the Aztecs! It’s only in American Imperial that

you can’t produce things the way you used to.

Chapter 132

THE LINE ITSELF (1950-2006)

... in the new landscape around them humanitarian considerations were becoming irrelevant.

—J. G. Ballard, 1964

B

ack then, said Javier Lupercio, meaning

back in the 1950s,

there were wooden benches at the crossing for people to rest, and the buildings were real small wooden buildings, and for the pedestrians there was only one customs officer. Up until 1980 and 1981, they had a patio-like thing that was the old one. They tore it down in about 1981. When that Port of Entry was built in Calexico, there weren’t all those businesses that are like in the tunnel when you come into Mexicali. There were a lot of robberies and muggings going on.

(The

Imperial Valley Press

reminds us that the Port of Entry was a triumph of human civilization. Dateline 1974:

POE opens new door to Mexico in era of friendship

.)

How old were you the first time you went to the United States?

Around seven or eight years.

225

At that young age, my mother had already put my papers in. She’d applied for green cards for the whole family.

What seemed different about the other side?

I noticed right away there were more job opportunities. The people were also different. Their way of being was different. I noticed all those small things that are also big things . . .—and he concluded with a yawn, because we were in the Park of the Child Heroes in midafternoon when it was very hot, so that the peculiar existence of Northside now and then remained of small importance.

It was afternoon; it was hot; indeed, in those long past days before the wall went up, Imperial’s binational delineation could still be overlooked on occasion. It had certainly not infected Greater Northside to any significant extent. That was the reason that by the time Operation Gatekeeper began, the Native American writer Leslie Marmon Silko would find herself looking back, with that special sort of angry cynicism that implies nostalgia, upon the 1950s, when they taught her in school that Americans could travel without restriction from state to state; for she had just learned what it was like to be stopped in the small hours in New Mexico by the Border Patrol.

I will never forget that night beside the highway. There was an awful feeling of menace and violence straining to break loose.

I myself never experienced that sensation, even when they detained me. The Border Patrolmen were often courteous; the Border Patrolwomen smilingly accepted my compliments. They could be kind. Sometimes they bought their prisoners soap with their own money, or they might share their dinner with a scared and hungry child. Once when a busload of captured illegals rolled past Salvation Mountain, the Border Patrol granted Leonard permission to board the bus so that he could pass out postcards for them to take home to Mexico.

On 28 August 1970, the day before he was shot dead by Los Angeles County sheriffs, Ruben Salazar published his last column, which stated in part:

The Mexican-American has the lowest education level, below either black or Anglo; the highest dropout rate; and the highest illiteracy rate.

Money trickles down like water; Mexican-Americans occupy lower dips of the moneyscape than Anglo-Americans, but there are lower places still. Four months earlier, this same journalist had written that

anyone who has seen the fetid shacks in which potential wetbacks live on the Mexican side of the border can better understand why those people become wetbacks.

Not wishing them to become wetbacks, Northside reacted accordingly. First there was no wall, then there were wall sections here and there, and immediately there were holes in them. (Even in 1999 I remember huge window-gaps in Calexico itself, huge spaces. You could reach through; you could step through. The next time I was there, those gaps were gone. Fresh stacks of fence lay in the setting sun, ready to be deployed elsewhere along the line. In 2005 there were still many easy gaps near Jacumba, in sight of the dirt road. My friend Larry and I stopped to admire one of those, and unsmiling Border Patrolmen drove up to us right away.)

In 1964, Northside caught forty-four thousand Mexican illegals—a decade later, seven hundred and ten thousand. Not content with the latter figure, a certain César Chávez informs us:

The worst invasion of illegal aliens in our history is taking a shameful toll of human misery . . . All of this stems from the unwillingness of the Border Patrol to do its job when that job might threaten the profits of the growers . . .

Poor Border Patrol! Couldn’t they please anyone?—They went on holding the line.

And what was the line itself but the red-reflectored white posts, staggered in height, the fresh-dragged tracks, the Border Patrol trucks everywhere? What is it now? Life continues to ignore and resist it. Very early on a Sunday morning in Calexico, a cool, cool manure-scented wind transforms palmtops into pennants, blowing away from the missing half of the high white moon, while the sun blazes dazzlingly but harmlessly at the end of the alley between Third and Second, gilding the crowns of the old square buildings and of the signs. The street remains unpeopled save by one darkskinned man with his jacket under his arm, slowly striding toward the border; the consciousness of Calexico is still plastered over with Chinese newspapers like the windows of the Aguila Super Market. As I transect another alley which last year was filled with water, I remember, an old citizen walks northward, toward me, with a newspaper tucked beneath his arm; an elderly Chinese lady in shorts briskly crosses Second Street, passing the triple-arched facade for Crystal Dream Travel; on the corner stands a security officer in white. I greet him and he replies with reserved courtesy, so I leave him.—Here in the windows of Christina’s Lingerie, a blonde mannequin in a loose blue camisole and matching blue panties whose translucence proves that she lacks a vulva gazes steadily outward, pushing at the window with her eternally outstretched hands, and beside her, another face has been newspapered over; a note reads: WE’VE MOVED TO THE NEW PARADISE, and then follows the name of an automobile. More female mannequins, these in summery outfits, and a plump golden dog trots toward a golden dumpster. Crossing First Street (Yoing Ju Ginseng Tea), I enter the bay between buildings which leads to the wall itself, where two white buses with people in them now begin to pull away, going north. And so I stand at the wall and gaze into Mexico. There’s the green sign for SAN LUIS RIO C, for SAN FELIPE and TIJUANA . It’s not yet seven, and traffic already waits to enter my country. A man named Señor Juan Pérez, tattooed and thirtyish, comes to shake my hand through the fence (Operation Gatekeeper has since made those handshakes impossible); he tells me about the old days of General Cantú, while a few feet deeper into Mexico, a girl in orange with a delightful sweatband is flirting with a newspaper vendor.

Chapter 133

FARM SIZE (1950-2006)

As the number of farmers decrease [

sic

], each farmer’s responsibility for feeding more people and animals increases. A gallon of gasoline or diesel produces more power in an hour than 300,000 pounds of horseflesh.

—The California Farmer, 1959

W

hy am I so struck with the

bygoneness

of the hay-heaps in the field of Mrs. Josephine Runge of Brawley, who got almost ten tons to the acre—the Imperial Valley record for 1927? First of all, because the competition of human beings for prizes and maximums is much less evident than it used to be. Secondly, more fields than ever are corporate Rothkoscapes: One resembles another. And if Company A produces a higher yield than Company B, I will never know it; in fact, when I go to the supermarket I lack any clue as to whose crops I am buying.

How did that bygoneness manifest itself? In American Imperial, it diminished the number of farms—and farmers—over time, correspondingly increasing each farm’s average acreage. In Mexican Imperial, it made the farmers more desperate for land. How could it not? At the beginning of the twenty-first century, twenty-five percent of working Mexicans were still farmers, while fewer than two percent of working Americans remained in that life.

In the Archivo Histórico del Municipio de Mexicali there is a twenty-nine-page list of

colonias

and their inhabitants drawn up in 1947. (Most of the

colonias,

by the way, contained just ten or twenty plots, although Colonia Mariana was not far beyond the pale with thirty-six.) This list is the only information the archive possesses regarding property holdings in the entire Mexicali Valley at this time, so it is as representative as we are going to get; and it proves that in spite of President Cárdenas’s best efforts to subdivide the Chandler Syndicate’s estates into equitable parcels, in spite of the protestations of an official of the Tribunal Unitario Agrario that in Baja California the

ejidos

were drawn up even more equitably than in other provinces—twenty hectares apiece, no more, no less—the few land documents from this period which survive show much the same sorts of small-scale inequality in acreages as prevailed in Los Angeles a century before! Well, but after all, these were

colonias,

not

ejidos.

The official was inclined to credit human error, remarking to me:

Not all the land was divided at once. So what you’re dealing with is land in the process of being divided up. So somebody probably thought he had twenty hectares, but it was really only seventeen.

Two examples:

226

In 1947, Colonia Villarreal divides eight hundred hectares among eighteen persons, families or partnerships. There seem to be twenty-five lots in all.

227

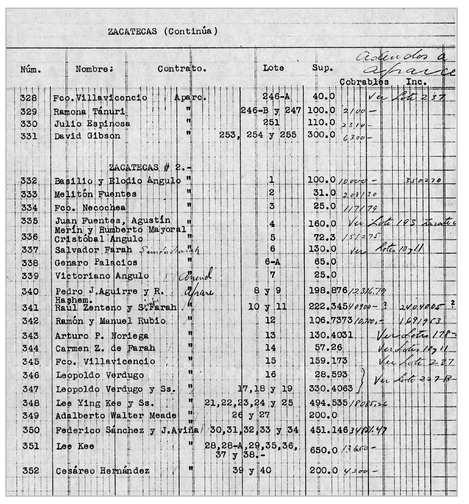

So each lot averages thirty-two hectares; the per capita acreage for those eighteen landholders works out to forty-four and a half. Meanwhile, Colonia Zacatecas in its two divisions has assigned nearly twenty-seven thousand hectares to three hundred and fifty-two landholders, who use four hundred and seventeen lots in all. The average acreage per lot is nearly sixty-four hectares (not quite Roosevelt’s hundred and sixty acres); per capita acreage is seventy-five and a half hectares.

What can be said? Yes, these inequalities may be locally significant; but compared to those within American Imperial, that hymn-singer of agrarian democracy, they are trifling.

In 1949, a young Congressman named Richard M. Nixon—who must have possessed extensive agricultural connections, for hadn’t he proved to the world that Alger Hiss hid Communist secrets inside a pumpkin?—visits Imperial County, a place where, according to a regional geography from that period,

farming is characterized by highly commercialized large scale operations . . .

(Where did Wilber Clark’s homestead go? I guess he couldn’t produce things the way he used to.)

Two statements made by Nixon should prove popular with the people of Imperial Valley. Nixon declared he is against the 160-acre limitation of ownership of lands demanded by the bureau of reclamation,

one of several institutions which the

Brawley News

resolutely relegates to lowercase,

and that he is against the department of interior’s grab for power.

Imperial remains victorious in both respects, for now. Although the United States Supreme Court will uphold the limitation, eight to zero, in its famous

Ivanhoe

decision of 1958, the Court then immediately permits the federal government to exempt certain water projects; and Chairman Clinton P. Anderson of the Subcommittee on Irrigation and Reclamation to the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs reminds us all:

It should be made clear to every Member of the Senate that, in many areas, 160 acres will not produce enough to support a family under today’s costs for machinery, transportation, and labor,

while Mr. Barrett (the Senator from Wyoming) adds his mite:

I say to the Senator from New Mexico now, as I have said to him privately, that I am hopeful his subcommittee will report the bill which will authorize a limitation higher than 160 acres for the Seedskadee project in my State.

So Imperial remains in step with her times; who could be more American than Imperial?

Page from a list of ladholders and renters in Colonia Zacatecas, 1947

In fact, how huge

are

Imperial County’s parcels? The regional geography just quoted from this period sees five thousand farms of a mere hundred acres each, tended by their

Mexicans, Orientals, Negroes, and migrant Caucasians under the direction of Caucasian foremen.

The place also had room for Harold Hunt’s eight-hundred-acre ranch near Holtville. Brahman blood survives hot climates, so a three-eighths Brahman X five-eighths Charollais was his choice cow. He had factory production so well worked out that his pastures carried two thousand pounds of beef per acre!