Imperial (121 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

(By the way, if a pound of beef needs twenty-five hundred gallons of water, then each of Mr. Hunt’s acres will require five million gallons of water to achieve its quota; his ranch therefore must drink four trillion gallons.)

In 1962, the Coachella Valley was apparently complying with the hundred-and-sixty-acre limit, but not the Imperial Valley. Steven H. Elmore of Brawley owned thousands of acres.

Far from fulfilling William Smythe’s breathless promise that irrigation agriculture would build a bulwark of middle-class democracy, the Imperial Valley became instead one of the most feudal landscapes in North America.

These words appear in a book called

Salt Dreams,

which asserts that average farm size in this area continually increased from the very beginning—this we have seen to be the case—and that in 1990 one in four Imperial County residents was officially classified as poor, which, alas, is also all too true.

If one includes in such a calculation the circumstances of approximately eight hundred thousand farmworkers who live in greater Mexicali but work seasonally in Imperial Valley, the gap between rich and poor grows even broader.

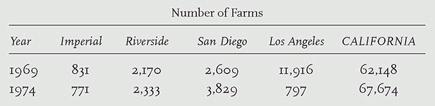

Such emphatic precision raises my suspicions—for who can even agree what constitutes a farm, let alone how to measure its size? For instance, in 1974, the number of farms in California was sixty-seven thousand, six hundred seventy-four by the 1974 definition, seventy-three thousand, nine hundred fifty-five by the 1959 definition.

Between 1969 and 1974, California’s total farm acreage decreased by four point six percent, while the average farm size increased from four hundred fifty-four to four hundred ninety-three acres. Since two-thirds of all California farms remained under a hundred acres in 1974, there must have been a few farms of nearly Chandleresque magnitude. This shows how useless, even treacherous, an average can be—a point which I will soon be compelled to make again. Nonetheless, since mathematical fanciness will only increase my conclusion’s self-doubt, let us proceed cautiously ahead, swiping at all obstacles with the Census Bureau’s 1974 definition of a farm.

Between 1940, when Hemingway’s hero Robert Jordan promised us that

most land is owned by those who farm it,

and 1974, the number of farms in California decreased by nearly half, and the average acreage almost doubled.

Now, what about American Imperial, or at least Imperial County?

When last we looked in upon the place from this perspective, in 1940-50, the numbers indicated that average farm size was growing less than California’s generally. In 1940 it was a hundred-odd acres.

228

In 1974 that was no longer the case; by the end of the century, hundred-acre Imperial farms would be positively quaint.

FARMS IN CALIFORNIA AND VARIOUS COUNTIES, 1969-74

Sources:

Census Bureau (1974), for both 1969 and 1974.

By 1974, the average farm acreages of those counties were: Imperial, six hundred sixty-six (down thirteen from 1969); Riverside, two hundred forty; San Diego, a hundred and seventy-nine; Los Angeles, two hundred and twenty-three.

Imperial County reported eight hundred and ninety-six

farm operators

in 1969 (do you think Wilber Clark would have been considered one of those?); in 1974 there were seven hundred and seventy-one. (You may remember that there were forty-five hundred separate farms in 1950.) Total land in farms decreased during that short interval from six hundred and eight thousand to five hundred and thirteen thousand acres,

229

although the acreage of actual harvested cropland remained about the same.

In 1974, Imperial County’s farm operators were burdened with a much higher average debt than their counterparts in the other counties. I wonder what the solution might be? Expand acreage, I suppose.

(Meanwhile, in 1976, hungry peasants from Sonora seized thousands of acres from eight hundred rich families. President Echeverría backed them up, then bestowed on them a quarter of a million acres more. Who was appeased? Landowners and capitalists were appalled; leftists sneered that it was only theater. People from this area, and from Jalisco and many other places south of Mexican Imperial, migrated in increasing multitudes to the border, forming

colonias

where they could and squatting otherwise.)

In 1979, Paul S. Taylor took out a sheet of yellow paper and once more pro-pounded his ancient question:

Is it “unfair” to require residents of Imperial Valley to observe reclamation law?

230

1.

Large landowners using the slogan “Call for Fairness” are appealing to Congress “to continue to exclude Imperial Valley from any acreage limitation on the land we own. We are asking this country to keep its promises to its citizens.”

In 1980, the Supreme Court answered Taylor at last, and overturned the hundred-and-sixty-acre limitation.

In 1982, only a hundred and fifty of Imperial County’s eight hundred and thirty-three farms occupied a thousand acres or more; but in 1993, the Bass brothers began to buy land in the county. Three years later they owned forty-two thousand acres—almost ten percent of the Imperial Valley.

In 2002, the United States Department of Agriculture prepared a county summary. The average size of a farm in Imperial County was now nine hundred and fifty-seven acres. The median size was four hundred and two acres. A hundred and fifty-eight of the county’s five hundred and thirty-seven farms were a thousand acres or more. Three hundred and seventy-one farms grossed a hundred thousand dollars or more.

One morning in Calexico when I asked the farmworker and occasional foreman Celestino Rivas, aged sixty-two, whether he thought Imperial County was rich or poor, he laughed contemptuously and said: It’s too rich! They call the ranchers here

the millionaires

! Right here, the farmers, when they sell their crops, they sell at a high price. When the season jumps to Bakersfield,

the millionaires

have sold to Bakersfield already . . .

He named a grower in El Centro with whom he had had dealings, and said: He’s like all the Americans:

I’m out of money!

A person who plants twenty-five hundred acres of broccoli . . .

FARM SIZE IN SELECTED CALIFORNIA COUNTIES, 2002

For purposes of comparison, the Reclamation Act of 1902 fixed a 160-acre homestead limit, and allowed 320 acres for a married couple. By 1918 the homestead limit had been adjusted to 320 acres for an arid homestead, and to 640 acres for cattle lands without a watering hole.

Source:

USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service: 2002 Census of Agriculture, County Data (accessed online, 4/4/07).

And Lupe Vásquez nodded, his eyes glittering with rage.

In 2002, Imperial County’s total farm acreage was 514,101—a less than seven percent decrease since 1954. But the county retained only a third as many farms.

As for Mexican Imperial, how much of that was being leased by Northsiders? God knows. I remember for instance Ejido Morelos, where they told me:

All of this is rented, mostly by Americans.

(José López from Jalisco, Mexico, 2003:

They grow a lot of crops here. I’ve heard there’s a lot of American companies that come here to pay cheaper wages.

)

In 2006 I asked Kay Brockman Bishop whether to her knowledge any family farms still existed in the valley, and she replied: But they’re still around!—She and her husband named several names, most of which I omit here.—Some of the farms have gotten huge, she continued, but the boys all farm with Dad. The Priest boys, some still work just like Dad did. Cute little kids. Then there’s Joe Wilson, who is probably sixty-seven, sixty-eight, something like that. He rents most of the ground on our ranch. His son who is forty-two or forty-three did most of the farming for him. Now he’s working another farm and so his Dad now has to hire everything. But he definitely learned from his Dad; I know so many people who farmed under their Dad . . .

Was it ever a hundred and sixty acres here?

It was always bigger farming here than that. It was harder to grow everything you need all year round. It was always a business, you’d say. I think it has to be.

Then she said: If you think Las Vegas has gamblers, try those vegetable guys.—She named a man and said: He went up and down just as far as you could go . . .

Chapter 134

WE NOW WORRY ABOUT THE SALE OF THE FRUIT COCKTAIL IN EUROPE (1948-2003)

The concept of progress acts as a protective mechanism to shield us from the terrors of the future.

—Frank Herbert, 1965

A

nd so American agriculture had truly won the victory. As for California (not to mention Imperial), she had beaten many competitors. Do you remember what Judge Farr, dead now these eighty-five years, wrote in his history?

The nights are always cool, affording restful sleep, while the sleeper dreams of his rapidly ripening fruit and their early arrival in the markets to catch the top prices ahead of other competitors in less favorable regions.

His dream came to pass. And Imperial’s fruit went on ripening, summer and winter. Imperial seized the day and perfumed the night with grapefruit blossoms.

Moreover, once that rapidly ripening fruit had entered the narrow zone between green hardness and bruisable softness, picking it had never been easier! In that midpoint year of the twentieth century, a U.S. Department of Agriculture article entitled “Science in the Agriculture of Tomorrow” boasted that in 1945 one

farm worker

(I guess the word

farmer

was no longer in fashion)

produced twice as much as did one farm worker 50 years ago.

That was on page one. Page two admitted:

Surpluses and how to dispose of them with a minimum of loss will always constitute a problem.

But please! Let the sleeper dream!

At the beginning of 1975, the California Freestone Peach Association reported that it had just had

the kind of year farmers pray for, with a good crop and a realistic price.

In 2003 an editorial in

The Sacramento Bee

explained that canned California peaches were falling out of favor, because Americans now preferred fresh Chilean grapes and other goodies. That was why

California peach farmers are intentionally shaking their trees with giant machines so that 14.5 million tons—yes, tons—of the fruit intended for canneries will instead fall to the ground and simply rot . . .

But it was not all bad news for the entity called Imperial, because

on the demand side, consumers in the winter increasingly are opting for fresh fruit available from the Imperial Valley, Mexico, Chile and other countries.

Imperial County’s growing season lasted just about three hundred and sixty-five days a year, to be sure, but why should big grocery stores care about that? If it wasn’t summer in Oregon, it might be summer in Peru. You can’t produce things the way you used to.

In 1948, California pears took in a hundred and twenty dollars a ton. A year later, they earned only thirty dollars a ton. The

California Farmer

advised:

It behooves every grower to produce a

moderate

quantity of top quality fruit in 1975.

A few pages later came this item:

We now worry about the sale of the fruit cocktail in Europe.

Chapter 135

THE WATER FARMERS (1951-2003)

In the first place, we might look into the American’s greed for gold. A German observes immediately that the American does not prize his possessions much unless he has worked for them himself; of this there are innumerable proofs, in spite of opposite appearances on the surface.