Imperial (135 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

In the California of Mr. Powell’s day, the citrus industry was getting rationalized and improved, to be sure. But in that epoch, when Wilber Clark’s automobile journey from Los Angeles to Imperial was a risky adventure and the first telephone line was little more than a fitfully operational strand of wire (some say barbed wire) strung from fencepost to fencepost, when the drinking water in El Centro was sometimes chocolate colored, and usually had to be strained or filtered, not everybody expected to drink chilled orange juice year round.

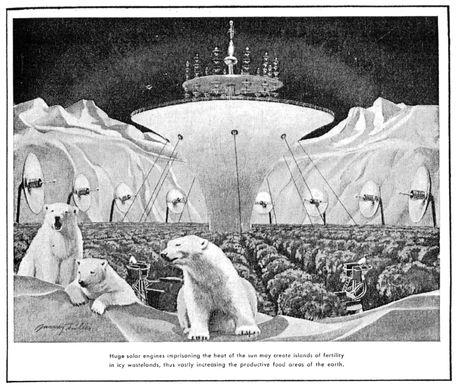

100 years from now...

WE MAY GROW ORANGES AT THE POLES

What will the world be like generations from now? Wonderful new products and methods will make living easier, pleasanter, safer. But in this marvelous new era, one old friend will still serve efficiently. Water and gas will be carried by rugged cast iron pipe laid today. For more than seventy American water and gas utilities, cast iron mains over a century old are still serving dependably. And modern cast iron pipe centrifugally cast and quality controlled...is far tougher and more durable.

U.S. Pipe is proud to be one of the leaders in a forward-looking industry whose service to the world is measured in centuries.

U. S. PIPE AND FOUNDRY COMPANY, General Office: Birmingham 2, Alabama

A WHOLLY INTEGRATED PRODUCER FROM MINES AND BLAST FURNACES TO FINISHED PIPE.

I am not for one minute proposing that those times were better. (As Eugene Dahm told me that day in the Pioneers Museum: Well, one of the biggest things is air-conditioning. Before we had electricity, we took a shower and moistened the sheets and tried to sleep before we started to sweat.) On the other hand, could there have been some point between 1899 and 1960 when a fitful supply of fresh orange juice could have resisted replacement by a homogeneously sugared three-hundred-and-sixty-five-day orange juice supply? And would that have preserved democracy in Arid America?

Some years ago, my uncle was trying to start a strange new business. He informed me that it would be quite possible for people to communicate with each other on their computers, and even buy things that way. I inquired why anyone would want to do that, and he replied:

All we have to do is create a demand.

And now there was a demand for

Home Grown, Thrifty Deciduous Fruit Trees of Best Varieties,

except that they weren’t homegrown anymore . . .

What if this dull tale about the sugaring of California orange juice were a parable about Imperial itself?

WATER IS HERE

. Accordingly, people get in the habit of using water. All we have to do is create a demand. The epigraph to this book, written in the year of Powell’s train ride through Imperial, is:

As long as a farmer has an abundance of water, he almost invariably yields to the temptation to use it freely, even though he gets no increased returns as a result.

And so more people use more water, and more, and until—

But that’s stupid; we’re not running out of orange juice! This chapter isn’t about water at all.

“THAT’S JUST THE WAY THE BUSINESS IS”

In the autumn of 2003, in the tiny settlement of Motor, Iowa, a farmer named Heemstra shot a farmer named Lyon in the head with his rifle. They were fighting over the Rodgers Place. As the

New York Times

explained the context:

Increasingly expensive tractors and combines and other mounting overhead costs . . . have led some farmers . . . to farm as much land as possible.

His farm has been highly improved. He made a success through his own efforts. And the murderer told the jury:

You have to spread these costs over more acres. Every farmer feels the need to grow. That’s just the way the business is.

Another farmer remarked:

In twenty years, there’s probably going to be twenty farmers in the whole county. It’s really depressing.

We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

Fortunately, this chapter isn’t about farmland at all; it’s about oranges and orange juice. Besides, Iowa has nothing to do with California.

FURTHERMORE

This chapter isn’t about winter lettuce, either.

NOT TO MENTION POLISHING BRASS

All we have to do is create a demand.

Or, in the words of the

California Cultivator,

1925:

The average housewife little realizes to what a variety of uses an ordinary lemon may be put. A lemon dipped in salt is an excellent brass polisher . . . Lemon juice brightens blond hair in all shades to Titian red.

But what if blondes want to stay blonde, or families get sick and tired of orange juice? Bank of America, 1941:

In the citrus industry the “on tree” inventory is of record or near record proportions . . . An astute job of marketing will be required.

Goddammit! Moreover, the United States Department of Agriculture has already noted a decline in Southern California citrus profits, thanks to competition with other points in America and the world.

256

The lovely old lithographed orange box labels give way to photolithographed

standard design elements,

because of

increased competitive pressure.

The Verifine Brand of Riverside obtrudes itself through little more than a glowing white V superimposed over a black pyramid, with colored rays on either side, like the decorative anti-aircraft lights in one of Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies. Meanwhile, the label of the Ultimate Brand of the Paramount Citrus Assn., Main Office Los Angeles, has decayed into two simple spoked wheels of red and yellow fire which may have something to do with orange slices. Whatever happened to the peacocks of Sunkist California Dream? That’s just the way the business is. Fortunately, Paramount also offers a Star Kiss Brand, whose reddish-blonde heroine, haloed in what to me resembles a slice of red onion, gazes long-lashed and red-lipped at two ripe oranges. The College Heights Orange & Lemon Assn. of Claremont, Los Angeles Co., California, introduces all of us to a rakishly fun-loving blonde in a mortar-board; why wouldn’t I eat

her

oranges? Siren and Adios, Majorette and Marquita, they’re all drop-dead gorgeous, because

attractive women continued to be a favorite subject until the final days of label production.

Orange groves dwindle.—An old lady who used to live in Riverside told me: The big thing was the smudging, to keep the orange trees warm. It was diesel heat. Our faces would all get black. In the fifties and sixties it started to go away.—Meanwhile, the wooden orange crates become cardboard, and the colored labels likewise go away.

At midcentury the USDA warns us that

eleven large cans of [orange] juice are available annually for each person in the United States.

What to do? (The summer grapefruit market remains good.

257

For better or worse, grapefruit juice will keep longer in storage than its citrus cousins.)

Use of citrus products must . . . be expanded and new products developed to avoid problems if surpluses of the crop should some time accumulate.

To me, this tale, which Imperial tells in so many ways, seems insane.

But I must be the only one. Bert Cochran, Vice President of McCann-Erickson Advertising Company, appointed to elucidate in 1952 by the Lemon Products Advisory Board, announces that

the basic idea, as we see it, of this . . . cooperative promotion is to finance the expansion of the total market for California lemon juice on a

completely equitable basis.

And so everybody cooperatively promotes, equitably or not, growing bigger and more entangled, so that by 1980 an internal Agricultural Labor Relations Board memo finds the relationship between citrus packers, growers and harvesters so potentially tortuous that it may be difficult for case workers to determine who is exploiting whom; but never mind; Bert Cochran’s

basic idea

has TRIUMPHED; because at the end of the twentieth century, Italy and the U.S. are the two primary lemon producers; and I’m patriotically proud to report that once again California dominates the American lemonscape.

Hooray for the Sunkist Vitamin C campaign! Whenever we wish to do our health a favor, we eat an orange or drink orange juice; never mind that broccoli and tomatoes contain just as much vitamin C: Oranges are not only sweeter, they’re more Californian; they’re

fun!

And so our citrusscapes look to be eternal. In the middle of the 1970s a man sets out to cross the border illegally into Northside, and consoles his wife: Don’t be sad because this time everything’s going to be good for me. Raymundo says that San Bernardino is really good with lots of oranges.

Indeed, by 1987, per capita citrus consumption in the United States is twenty-eight point one six pounds—more than fourteen pounds of that oranges, and nearly seven pounds of it grapefruit. In 1988, we manage to swill down seven hundred and ninety-seven million gallons of orange juice!

But in 1992, we drown in citrus nonetheless, and a specialist laments:

Citrus wines have never achieved the high popularity of grape wines due primarily to flavor problems still unsolved.

By 2004, Brazil can place a pound of frozen orange juice concentrate on the American market for less than seventy-five cents; whereas it costs Florida ninety-nine cents. Thank God for our twenty-nine-cent tariff!

Prudently, Florida puts a million dollars or more a year into research and development. Result: a “ canopy shaker” which can harvest a hundred trees in fifteen minutes. Four pickers would have taken all day.

That year Orange County does not have so very much to do with oranges; and as I ride up Highway 91 toward Riverside, enjoying that gentle slope of freeway up to the dusty mountains, my eyes taste another Lemon here, another Euclid there in Fullerton. Fresno, Ventura, Kern and Tulare counties still grow citrus; meanwhile, says a local history,

only tiny lots of old orange or lemon trees remain in production in the Inland Valley.

Across the street from the Riverside courthouse, in front of the parking garage, a clock whose face is an orange slice spills water down a widening V-shaped channel into a fountain. What do oranges mean in Riverside nowadays? Lori A. Yates, President of Victoria Avenue Forever (once upon a time, Victoria Avenue was ten miles long and a hundred and seventy-five feet wide with a thirty-six-foot median garden), finds it necessary to explain

how incredibly important the citrus industry was to the city of Riverside.

Meanwhile, the wall of the Mission Inn Museum informs us that

Frank Augustus Miller (1857-1935) brought to Riverside the vision, dedication and commitment necessary to transform a citrus-based community into an international destination.

In other words, Frank Augustus Miller helped get rid of oranges.

Sprayed with miticides and insecticides, irrigated with the guidance of sunken tensiometers, mechanically pruned, dosed with such growth regulators as 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, which

delays and reduces the drop of mature fruit as well as delaying the aging of the fruit,

still picked by human beings on ladders but graded by

an electronic color sorter, at a speed difficult for the eye to discern,

Riverside’s oranges continue to grow

in isolated areas which are less visible from our freeways—

for instance, in Coachella.

On Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, there is an intersecting street called Orange, and even an El Centro. On Freeway 10, going west from Euclid, evening bestows a reddish-orange glow like neon peaches hanging over us: fiery smog-clouds standing out against the greenish sky; they are extremely beautiful, far more so than the smoke-bruised sunset sky of Mexicali.—I coast by Orange Grove Ave. beneath a fiery-orange sky.—Although grapefruit has been memorialized all the way to Los Angeles’s Fourth Street, where the old grimy-white pillar-pairs of the Farmers & Merchants Bank guard the pale fruitlike globes of a chandelier which offers itself to us through the dark-glassed arch of the doorway, the future of Southern California’s citriculture, defeated by Florida’s, may well be as ghastly white as a trailer park’s rooftops under floodlights on Montclair; but never mind; West Covina has a Citrus Street . . .