Imperial (138 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

It’s been three years that we haven’t played any

narcocorridos,

said Alfonso Rodríguez Ibarra, the

programador

at Radiorama Mexicali. Three years ago the people who owned the station and all of their affiliates decided to stop. But a year ago, the government of Baja California made it a policy not to play them.

In your opinion is that a good thing or a bad thing?

A good thing just from the marketing standpoint, he said. If we played

narcocorridos,

there are enough people who would be offended that we would lose the advertising. That’s the reason they’re not playing them in Sonora, either.

And in Sinaloa?

In Sinaloa I know there is a government decree.

He preferred the traditional

corridos,

the ones about horses and the like. His favorites (and here he started to smile and nod his head as if he could hear them) were “Caballo Blanco,” “Katrina y los Rurales,” “Lamberto Quintero” and “El Cantador.”

You know it’s a

corrido

when you listen and it’s telling you a story or a legend, not necessarily about love but about a man who fell in love or about a man who had a rooster for his best friend . . .

Here’s a story for you, or, if you like, a legend: On Saturday, 22 March 2003, Anna Francis Warner, aged thirty-one, was arrested at Centinela State Prison.

The woman was taken into custody at about 11:45 p.m. and taken to Pioneers Memorial Hospital in Brawley, where an X-ray revealed the contraband hidden in her vagina. Two bindles of methamphetamine weighing 4.5 grams were recovered . . . The woman then implicated a male accomplice who was staying at the Budget Hotel in El Centro.

What a nasty tale! Who would want to set that to music? I imagine the anxiety she must have felt, then outright dread, and a shock of doom, followed by futile excuses, then the invasive humilation of a policewoman’s gloved finger in her womb, followed by arrest, confession, detention, conviction, sentence.—

How do you plead?—Guilty. No contest.

Then what? More punishment, more humiliation. I doubt that it would have brought a smile to Lupe’s face. But if what happened to her could be recast as a tragic tale of love and daring—and why not? What if the

male accomplice

were her lover? What if she smuggled with art and grace? What if wretchedness could be magicked into grandeur? Why, then, Anna Francis Warner’s fate might become quite

a good thing from a marketing standpoint

—not to Alfonso Rodríguez Ibarra, I grant, nor to María the cleaning lady in Sacramento, who was acquainted with the

narcocorridos

but preferred the ones which were not about drugs; but very possibly

a good thing

to my friends who sleep in abandoned buildings as did José López from Jalisco, who by the way has disappeared and whom I miss; to those who sleep in the park as did the dark street prostitute Érica, who slept only

bit by bit,

as she put it, since otherwise somebody would be sure to cut her purse away from her; I will introduce you to her very soon. For now, let me introduce you to Anna Francis Warner’s

narcocorrido

counterpart, “The Queen of the South.”

Manola Céspedes said, “Teresa takes risks;

she sells drugs in France, Africa and Italy;

even the Russians buy from the powerful auntie.”

She was smart enough to use the Spanish accent;

she showed off her power like a noble lady;

Teresa the Mexican surprised them all!

Sometimes she wore the clothes of her land;

once she wore crocodile boots and an ostrich jacket;

she wore a belt that whistled and drank tequila that jumped.

What happened to Anna Francis Warner? What happened to Miguel Palominos? Why not hope for the best, as the Tigres del Norte did in that

narcocorrido?

Some say she’s in prison, others in Italy,

in California or Miami, somewhere in America.

Anna took risks; she sold drugs in California; Anna surprised them all . . .

The policeman Carlos Pérez said that some of the most famous ballads were about Jesús Malaverde, whom he called

the patron saint of the narcotraffickers.

—They bear his image, he said. For those who use drugs, he’s like a saint. Downtown, they show his statues. He lived in Sinaloa. He was Robin Hood. He sold drugs and used the money to help the people. He was killed in a gun battle because he didn’t want to give himself up. Some say he was never caught. Some say he died of old age, and others say that he is still alive. Everybody has his own story.

259

I asked him whether he knew any local narco-ballads, and he replied: Most of the bad guys are Sinaloan. Here in Mexicali, there’s just middle management. But I’ve heard a

corrido

about three Colombians in Mexicali. So the three Colombians kill the police commandant . . .

His colleague, Juan Carlos Martínez Caro, explained the genesis of the ballads thus: So the people who were dealing drugs paid singers to write songs about them. It began in the sixties. It’s a way to make themselves look good.

I cannot say that I was greatly surprised to learn that Officer Caro preferred those

corridos

praising the police who captured and killed drug traffickers, such as “Comandante Reynosa.” What a good thing just from the marketing standpoint! But other individuals, some of whom were to be found at the Thirteen Negro, were fonder of the

corridos pesados,

260

the heavy ballads, the hardcore ones.

I don’t listen to them, said Officer Caro, because they portray the life of drug traffickers as good and it is not. So if you are at a party and they start playing a

narcocorrido,

people get angry at the police. In some places, the government prohibits them since they incite violence . . .

THE CITY OF HAWAII

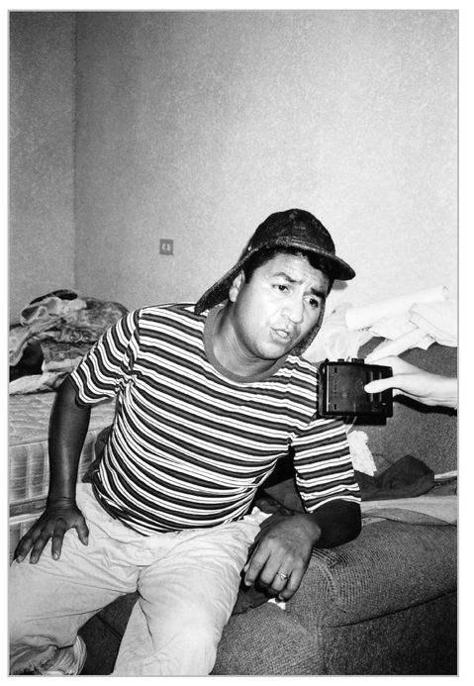

Just then there came an ex-policeman of eagerly jaunty sadness, bearing roses and dinner for his policewoman wife, who accepted his offerings without enthusiasm. His name was Francisco Cedeño, and he was now Christ’s age. He invited me home, so we drove to Colonia Luisa Blanco, where behind a wall of plywood lurked a one-room palace, anonymously male and disarrayed.

He was an ex-policeman who had enlisted in the military in his early teens. A small table was strewn with photographs of his various adventures in uniform. He was immensely proud of these souvenirs, and especially of his police memorabilia, and it caught at my heart when he said straight out: Three years ago I contracted some vices and was fired.

I’m sorry, I said.

He shrugged.—I had to pay the price of life.

Then he said: Not to justify it, but one reason I fell into vices was the lack of love from my parents.

He showed me a photo of a hectare of marijuana in Sinaloa. And here was a photo of an

amapola

drug flower. Here he was in the army at sixteen (it was an important stage of my life, he said wistfully), and here in police uniform at an official reception . . .

I got married very young, he said. My wife got pregnant, but because we couldn’t have children,

261

I partied a lot with a lot of women. I was about to lose my marriage when I heard that my biological father wanted to know me before he died of cirrhosis; he sent me a Greyhound bus ticket to Fresno. He bought me some documents and taught me to speak a little English ...

262

He showed me a photo of himself with the father who had actually raised him, the one he loved with all his heart. Here was a photo of the family with a chocolate cake and an eight-year-old boy in a cowboy hat; that was Francisco Cedeño. About the other father, the one in Fresno, he said: He abandoned my mother and didn’t think about his kids.

Here’s where I got married, he said, showing me a photo of two scared children. You can see she still looks the same.

She didn’t, of course. She had become sour and stern, and it wasn’t just the uniform. Disappointment has a way of replacing fear with certainty.

My father taught me that you need to give everything to your job, he was explaining. My wife was annoyed most of the time I was involved with the government. So one day I had to choose between my wife and my job. I chose my job. So at that time she told me I had to do everything possible to have a child or she would leave me. So I decided to find out which drug would help me perform sexually. It was crack. It had many vitamins from mares and things like that. I lost my job due to my drug problem.

I nodded in silence.

The story of narcotraffic starts in 1945, he said abruptly. There is no organized crime without protection in government. Here you can find yourself in trouble without wanting to. By the way, this Mafia is run by families. But a person like me, well, I grew up on a ranch; I didn’t know anyone. But if I have a brother who’s a drug dealer and I’m in the military, I’m not gonna catch my brother. If my brother harvests marijuana, I’m gonna protect him. But to do that I have to share money with my bosses.

First you harvest it, and he showed me another photo. The owner of this field is a politician. It’s not easy when you walk with God, but then no one harms you.

The next photograph depicted soldiers destroying a field.—But behind this field, said Francisco Cedeño with what I was already calling the

narcocorrido

smile, there are five more, even bigger! We just took our orders; we were supposed to destroy one and leave five, because if you didn’t follow orders you didn’t live to tell about it. So they take it, they harvest it, pack it up, hide it in hollow trees, then put it on boats to San Felipe. Other batches they take by small plane. Doctors who go into the hills to help women and children carry the drugs. Problem is, it grows. And when it takes time to grow, there’s risk. So they’ve developed a new method where you can grow it in any house, little crops in water. They do it in tract houses, motor homes, and especially houses under construction so you can have people outside working, but inside everyone’s

really

working.

I heard

narcocorridos

in the military. Everyone enjoyed them. There are people worthy of respect in the military and the police who don’t do drugs. But everyone listens.

I composed one for my wife, he said, and here I thought again of that weary, bitter, slender policewoman to whom he brought dinner and roses, and with whom he claimed to read the Bible every day. There was no sign of her in this sweltering concrete cube of a home with one naked mattress halfway sliding off the other—not a slip or a bra, no stray high heel, no lipstick; but I didn’t snoop in the closet; maybe all her things were neatly there; but everything I saw was a solitary man’s, like a drug runner’s, in this one room where rebar stuck out of the wall and dust lay upon his old photos and certificates, not to mention again that bare and grimy mattress with covers merely messing it up and clothes disarraying the covers; his life’s metonym might be the open suitcase on the bed, or perhaps the widowed bird (he killed his wife by pecking her, said Francisco). He stayed in shape, however; he cared about his appearance. There lay barbells by the mirror. But this house hidden from the street behind a wall of plywood, this was what I found creepy. Now he began to search everywhere for the

corrido

he had written in honor of his wife, but he couldn’t find it, so, changing his clothes and donning a hat to formalize the performance, he sang what snatches he remembered into Terrie’s tape recorder, and here is what she transcribed and translated:

In Baja California

there are very valiant women.

Don’t take my word for it;

all the people say it!

This

corrido

is for them;

I’m always thinking of them.

There is one I carry in my chest,

or my soul it could be called.

Even for many eggs

263

I wouldn’t want to trade her.

The way she carries herself

makes the people respect her.

She’s a

norteña,

this valiant woman.

Some call them

patrona

because they give us food.

Some love drug dealers;

some love the law!

That was as much as he could remember. The invocations of

valiancy

and

respect

could have been heard in any

narcocorrido,

for instance, in “The Queen of the South”—Teresa the Mexican from the other side of the sea, a valiant woman we’ll never forget—and indeed this devout lover of the law had also composed a

narcocorrido,

“The City of Hawaii”:

In the year ’95,

October thirtieth was the day,

In the city of Hawaii

the story unfolded.

They detained two

narcos

who sold pure

chiva

*

from a pueblo in Nayarit.

They brought the drugs

hidden in a Grand Marquis—

who would even guess?

They dressed like priests

so they wouldn’t get searched . . .

That, too, was as much as he could remember. Of course it would end badly, as life does, or else get bad temporarily, then escape from the badness as death does. Did the two false priests, having perhaps employed the power of their Lord to drive across the waves of the Pacific, remain in a Hawaiian jail forever? In its incompleteness, their story mirrored the career of Miguel Palominos, whom I assume to be serving his fifteen years, because

sympathy has no place in the courtroom, and the jurors were told that four times.

When I think of Miguel Palominos, and when I think of Francisco Cedeño, the words of a certain prohibited ballad rush into my mind: