Imperial (145 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

After all, can millions of ecstatic

maquiladora

laborers be wrong? Down in Ejido Chilpancingo, the place which Mr. D.’s report had described as

now a fetid, polluted barrio

thanks to contamination from Metales y Derivados, I interviewed the twenty-four-year-old

272

Benjamín Prieto, who wore a baseball cap and sat on a park bench. Fifteen years ago, his family had moved here from Mexico City. He had worked in the Hyundai and Honda plants; now he was beginning his second year at Sony and earning a thousand pesos a week.

Which factory is the best?

Sony, because you learn more about electronics. I want to study and get a degree in electromechanical engineering.

Señor Prieto was happily unacquainted with Metales y Derivados; likewise everyone else I interviewed in Chilpancingo. (Summation of the NAFTA report, 11 February 2004:

The level of lead contaminants found on the site is 551 times greater than

that recommended by the EPA . . . for the restoration of contaminated residences. At

[

a

]

one mile distance from the plant, the level of lead contamination could still be more than 55 times higher than the highest level based on EPA norms. The Metales y Derivados site is located just 600 meters from Colonia Chilpancingo, home to more than 10,000 residents.

)

Did you ever hear any stories about people getting contaminated?

No.

And if someone told you such a story, would you believe it?

No, he said firmly.

Thanking this true believer, I moved on, and sometimes on my travels I even met other exponents of

here there is life.

THE HOLE

About Metales y Derivados (which on the phone Mr. D. referred to as one of

those old polluting assholes

) I will tell you that it was not quite as easy to find as the aforesaid Mr. D. promised. Fortunately, Terrie and I had all the time and money in the world. Now, where might it be? Well, where might one expect to locate the most distinguished

maquiladoras

?—My hypothesis: in a place where the air tastes metallic on the tongue and the eyes sting a trifle!—Up in the Nuevo Tijuana Industrial Park, which actually didn’t appear so new anymore (sparks, heaps of metal, a stink, pallets next to peeling-painted sheds), red buses waited outside a

maquiladora.

A man advised me to go to the delegation where

maquiladoras

are registered. But official channels are rarely one’s best connections to bad news, which may sometimes be a synonym for truth. So let’s take a spin up and down that central strip of factories along Bellas Artes. Let’s ask at Frialsa Frigofor; oh, and here’s a satellite Bizco

273

plant, this one flying the American flag. (Mr. D.’s report:

Babbitcor Bizco Cashcare. In front of Óptica Sola on Insurgentes. Another company with a bad reputation.

)

And then, right on the mesa’s edge, the ruin of Metales and Derivados unmistakably stood; and as we got closer there was a salty rancid smell. A sign on the fence warned of danger, but a convenient hole invited us to enter, and in we went. Our eyes began to sting. Mr. D. had said he felt sick the day he strolled about this monument to human selfishness, which in its own way was as eerie as an Indian cliff-dwelling, or even more so, being poisonous, not that I’d ever credit any stories about anyone’s getting contaminated. The sharp flapping of black tarps in the wind was the only sound. In other words, here there’s life.

Rotting metal, said Terrie, who’d not done well in high school chemistry. What rots metal?

We gazed at those corroded drums under the tarps, and after a long time Terrie said: My mouth tastes as if I’ve been sucking on a penny.

I’m sorry you haven’t reproduced, I told her. And I’m glad that I already have.

Under the heaving tarps, squarish skeletons of lead were nightmarish, but nightmares can’t hurt you. This comprised, in fact, the corpus delicti: six thousand metric tons of illegally abandoned lead slag. I can’t comprehend that; call it a nightmare.

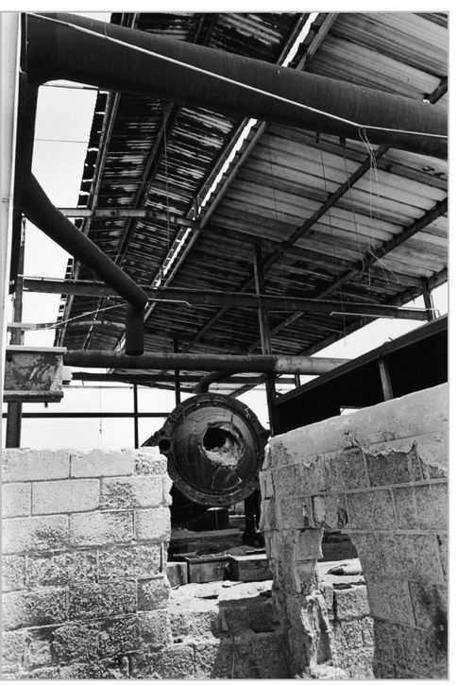

In June 1989, I have read, the place held two lead-smelting furnaces, two crucibles for lead refining and two copper smelting furnaces. In 1993, the final year of operation, three rotary lead-smelting furnaces had existed, but only one remained in use. The cannons I saw must be those furnaces. We need have no fear that our lands will not get better and better as the years go by. I admired the view of the great canyon below, which crawled with houses and shanties. Sunflowers grew near the mountains of old batteries.

Inside the great shed, which felt like the focal point just as the restored gas chamber feels like the focal point of Auschwitz (and isn’t this simile overwrought, even unfair? But I have visited Auschwitz, and I remember the

heavy darkness

of the gas chamber, much heavier than here, to be sure; but that memory visited me unbidden as I stood there feeling sickish in several ways, wondering how many children down there in Chilpancingo were enjoying the benefits of lead poisoning; Metales y Derivados felt like a wicked, dangerous place, I can tell you; by comparison, those barracks for the campesinos in Ejido Tabasco began to seem attractive), several huge rusty drumlike apparati were trained like cannons at the barrio below. What were they, those red-crusted hulks? They had wheel-gears on them. I stared at them with my burning eyes; I smelled the sour-metal smell. And those square pits in the concrete floor, those pipes going down, down into the reddish earth, what did they signify?

Across the street, well within smelling-range of that rotten-metal smell, two men sat eating their lunch. I asked if I could photograph them, and they said that I could, but they’d get in trouble if they failed to don their protective gear first; so they laid down their sandwiches, dressed up like astronauts, and stood behind the sign which said

PELIGROSO

, meaning

DANGEROUS

. Meanwhile, a black rat silently rushed past another drum. They were supposed to be cleaning up this place for the company Rimsa, on contract with the Mexican government; and later I met their foreman, who identified himself only as Jaime, and who said: The first thing our government did was try to work with the owners. But it was going to cost so much that the owners left for the U.S.

Metalesy Derivados

How will Rimsa clean it up?

We’re bringing big dump trucks. They’ll take it to the U.S.

How do you feel about this place?

For me it’s a criminal act. Mexico opened its door to American people, and the only interest is to make money.

“THEY’VE ALL BEEN PRETTY GOOD”

How many times have I heard this same indictment? The year before we bombed Kosovo, an old Serbian woman shouted at me: You Americans have no souls! You’re only about money. But in heaven we’ll all be equal.—And now the same accusation rose up against us from smog and grimy white sprawl on grubby grey-green Mexican hills.

The sickness of capitalism, the American sickness, is what gets transmitted at what Marx labels

the cash nexus.

My own theory, which is not particularly Marxian, is that each place possesses its own sickness. Mexicans and Serbs are no healthier than we. If it’s the cold American mercantile sickness which seeds the Mexican borderland with such

maquiladoras

as Metales y Derivados, what’s the Mexican sickness which allows them to flourish? I’d say it’s this: In Mexico, people cut corners and do what’s easiest even when it’s not what’s best. That man in Pedregal ignored the admonition of his own black cough; and I also remember a

maquiladora

worker named Marí (short for María), whom I met in Pancho’s bar in Mexicali: Thirty-eight years old, born in Mexicali, the mother of two boys and a girl, she had come to Pancho’s with her friend “just to have fun,” she said, a little embarrassed. Marí had worked in

maquiladoras

for many years. She was now at the

maquiladora

“Cardinal,” which made transparent plastic masks for hospitals. She didn’t know who owned it; Mexicans, she thought.

274

—For me, it’s not a good job, she said. I’ve been working here six years, for eighty-three pesos a day, eight hours a day. I make the masks that go in your nose . . .

How do you make them?

With my hands.

When I asked her how many she made in a day, I saw how the girl sat thinking, struggling with what would have been for anyone with a Northside education an elementary calculation: I don’t know how long it takes me to make one. It’s really fast. I don’t know exactly how many I make in a day, but it’s a lot. I make twenty boxes and each box has fifty masks.

She got a half-hour for lunch, and didn’t mind that.—It’s a really clean factory, she said suddenly. The managers are nice with me. Probably the best thing is that it’s air-conditioned and it’s very clean . . .

The workers had a kitchen to cook in, and Cardinal also sold food, “everything,” very cheaply, just a few pesos.

Marí lived in the

colonia

Seventh of January, which was very far—an hour each way by bus, which cost four pesos fifty. Fortunately, Cardinal provided a free red shuttlebus which took her forty-five minutes, and when I asked her why she had stayed all these years, she said: Maybe because they provide transportation, because my shift ends at eleven-thirty at night, so I can’t be wandering around.

It was mainly women who worked at Cardinal—about five hundred people total, she guessed.

Do they ever give pregnancy tests?

There is a pregnancy test only when you begin to work there. But the men get tested for drugs every six months.

Most of the

maquiladoras

where she worked required pregnancy tests at the beginning. Marí had never worked at any facility which required a monthly test.

Do you feel that the pregnancy tests are invasive?

Sometimes the ones who are pregnant can’t work, she said in a flat tone. It happened to my friend.

How often has a boss asked you to sleep with him and you feel that your job may be at stake?

It’s never happened to me. But there are some people who experience it.

(Terrie believed that something had in fact happened to her which she was too embarrassed or upset to tell; she could see it in her face, Terrie later said.)

Which

maquiladora

job was the best?

They’ve all been pretty good.

So are the

maquiladoras

good or bad?

I don’t have any studies, so they’re good for me.

Why not be a campesina?

Because here in Mexicali there’s not that opportunity. One must live in the

ejidos.

Would you prefer to live in an

ejido

and be a campesina?

I used to live in an

ejido

and I worked as a

campo

with my parents, she replied, which I thought was not much of an answer.

So that was Marí, and you’ve met the man with the black cough, and finally there were those two men who surely understood that Metales y Derivados was an extremely dangerous place, since they had been hired to decontaminate it, yet who sat in the lead-tainted dirt eating lunches seasoned with lead. In short,

here there is life.

That legal assessor for a federation of labor unions whom I have quoted before (his name was Sergio Rivera Gómez) insisted: The

maquiladoras

are

good

for the population of Baja California, because there is a lot of unemployment in the five Mexico municipalities. And the work that is offered, especially to homeless people, offers benefits.

If there were campesino work for all at the same wage, would people prefer that?

Some would be interested, but the majority would not want to work in the

campo,

thanks to the extreme climate in Mexicali and other regions of Baja California, which makes the work very difficult. In the

maquiladoras,

they have air-conditioning and a lot of advantages.

“WHAT MAKES THE PRODUCT COMFORTABLE”

Above the smog, in the stinging air of the steep hills overlooking Insurgentes Boulevard, in a

colonia

called Villa Cruz, lived a very young-looking young man named Lázaro, small and slender, smoothskinned with a slight moustache. His wet hair was combed back as he stood outside the partly whitewashed, partly greywashed shack where he lived with four others, two of whom worked in

maquiladoras.

In the dirt, an older man, his visiting Pentecostal uncle, stood writing something in the family Bible, using an old refrigerator for a table. We could all see down into the Tijuana Valley, down into its smog and grime; we might as well have been peering down into the poison-clouds of Jupiter. I could make out Óptica Sola below us, wide and white. That was where Lázaro worked nine hours a day, with the usual half-hour break, four-thirty in the afternoon until one in the morning, Monday through Friday, earning eight hundred pesos a week after taxes. (Southside

versus

Northside: They make in a week what we make in a day.

275

)