Imperial (148 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

That was what he said about those

maquiladoras

, and it was all plausible although he never came close to proving that any of it was true, perhaps because he did not care or was not competent or perhaps because his standards of proof differed from mine, or, most likely, because thanks to the secrecy of the companies and poor record-keeping generally, it simply could not be proved. But let me press on nevertheless in this account of one more deficient attempt to apodictically comprehend the region which this book calls Imperial: I now had Mr. D.’s report and Señor A.’s advice and promises. The plan would be to investigate Formosa and Óptica Sola to see if they were poisoners; and we would investigate Matsushita regarding allegations of sexual exploitation.

I have an ex-employee of Matsushita, Señor A. had said. She can be here on Friday, and she can tell you how they have many modeling contests in Matsushita, frequently. And this is also the factory where they ask women to take the pregnancy test every month.

In the end, the alleged witness of Matsushita’s modeling contests (now twenty-one years old, the detective told me; she had supposedly worked in this

maquiladora

from January through June of 2003) did not come, out of anxiety, Señor A. reported. Upon my request, he later forwarded his own transcript of an interview, bearing her full name (which she did not wish to be published) and, among other matter, the following:

Q What happened between you and the management of Matsushita regarding sexual pressure? Tell us everything that you remember.

A Look, it’s very embarrassing to talk about the time that I worked there . . . When I first started they assigned me to production. My boss was Díaz, the engineer, and about two weeks after I started working there—it was on a Friday—I was told to call the quality control manager, and he told me that I was going to lose my punctuality bonus because I was getting there late. I told him that my time card said the time that I arrived and that I was not getting there late. When I told him that, he looked at me and said that the time card didn’t matter, but if I would agree to go out with him I would continue to receive my punctuality bonus, and I told him no and I left his office.

Everything seemed fine for about two months until at the beginning of April when they didn’t pay me my punctuality bonus. I went to see my production chief and he sent me to a man, a tall white man who was very well-dressed. I explained to him that I had not been paid my punctuality bonus and he said that if I agreed to have a few beers with him, the problem would be taken care of. I told him that I wouldn’t put myself in that situation. I left his office and then I only lasted about three more weeks before I changed jobs.

Q How did this affect you ... ?

A . . . Now I last only a short time on jobs. At first I start out fine but when I hear people laughing, I think they are laughing at me, and then I start to dislike my job. That’s why I only last three or four months at the jobs I have had.

Q Do you still work in factories?

A Not anymore . . . Since then I worked in a bakery and later in a supermarket, and now I don’t have a job but I don’t want to work in a factory.

Q Do you believe that they respect women at Matsushita?

A Of course not.

The evidentiary value of this interview must be considered lower than that of the conversation with Lázaro about Óptica Sola; because I never met the subject, whose existence for all I know may be fabricated, although I don’t believe that Señor A. would do this; he did a good mediocre job, entertaining me with occasional colorful exaggerations, to be sure; but I never found him being willfully dishonest.

The young woman’s testimony reads credibly to me, although her reaction seems disproportionate. You will have noticed that the modeling contests remained unmentioned. I wish that I could have interviewed her myself, for it is possible that the situation in which she found herself was still more difficult and unpleasant than this brief account states. I especially would have liked to know whether or not she ever got her punctuality bonus.

At any rate, Perla, who was very outspoken and whom I came to admire for her courage and to trust not only for her perfect reliability, her patient caution, her openness about her life, her verifiable knowledge of reality, but most of all for her readiness to admit ignorance and error, assured me that ten or twelve years ago, the employees of Matsushita were

all eighteen- to twenty-five-year-olds in miniskirts.

She used to visit one acquaintance on the job, so she’d seen for herself. She also knew someone who was fired on her twenty-fifth birthday, maybe or maybe not for that reason.

Here in Tijuana, Señor A. had said, they have an event called Miss Maquiladora, and what it becomes is a prostitution ring for high-level executives. There will be a woman who works on the line who gets invited to be an assistant to the President. It normally happens in the springtime. Wives talk about it. Each

maquiladora

sends a woman. They go to a contest in Rosarita. High-level executives attend. It’s a meat market. All of a sudden, you’ll notice that this poor woman moves to a middle-class neighborhood, and the women who are actually trained to be assistants complain.

281

So Matsushita participates?

Of course.

I am told, but have not verified, that in 1993 or 1994, the head of the federal Procuraduría de los Derechos Humanos investigated sexual harassment at Matsushita. The finding remains unknown to me. The labor activist who relayed this information, Jaime Cota, also

recalled taking complaints from female employees at Matsushita/Panasonic [note: He seemed

to

believe this was the same company] years ago. The women were solderers who fainted because of inhalation of lead . . .

He

categorized most labor disputes as related to “unfair termination, low wages,” but occasionally for “environmental” reasons. In my follow-up interview with Cota

(this is my detective Mr. Raskin speaking)

he stated that of our subject group Matsushita, Tompson

[

sic

]

and Optica Sola had most of the labor complaints he handled.

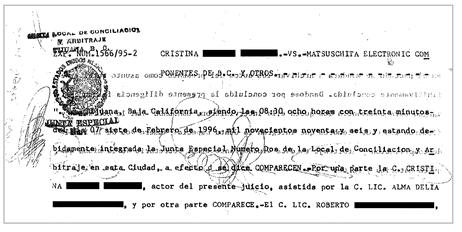

In addition, Señor Cota furnished Mr. Raskin with a copy of an out-of-court legal settlement between Matsushita and a former employee. From the look of this document, the grievance dates from 1995:

From the deposition of Francisco

282

———:

3. When Señora Cristina——worked at the suede company, you were her supervisor.

4. Señora Cristina——————presented several complaints to the Human Resources Dept. of the company against you.

5. When Señora Cristina——————worked at the suede company, you knew that she had complained on several occasions that you bothered her by harassing her sexually.

6. The Dept. of Human Resources ignored her complaints against you.

7. On 6/30/95, at approximately 10:00, you forcibly kissed and embraced Señora Cristina——————when she was at her work station.

From the settlement:

To the plaintiff, who has been duly confirmed in this judgement, the company agrees to pay 3,000

[handwritten above this: 11,000]

pesos, an amount that will be paid today at 11 am, before this Authority, an amount that covers salary, seniority, vacation time proportionally to the services provided by the plaintiff to the company.

In this same year 1995, the organization Human Rights Watch investigated forty-three

maquiladoras.

I quote from its report: . . .

Along the U.S.-Mexico border, from Tijuana to Matamoros, we found, with few exceptions, that . . . employers require women applicants to submit to pregnancy exams, most commonly given through urine samples . . . Maquiladora staff also try to determine a woman’s pregnancy status by asking intrusive questions about the woman applicant’s menses schedule, whether she is sexually active, or what type of birth control she uses . . . Should she become pregnant shortly after starting to work, maquiladora managers sometimes attempt to reassign women to more physically difficult work or demand overtime work in an effort to force the pregnant woman to resign . . .

Regarding pregnancy tests as compulsory for employment,

the implicated companies

include

Panasonic (Osaka, Japan-based Matsushita Electric Works).

Dr. Adela Moreno, whom Matsushita employed in 1993, told Human Rights Watch:

It seemed that was all I did. I was appalled, but I did the pregnancy exams. At times I would be so angry . . . and so fed up with how they were exploiting those very young girls that I would tell

the supervisor

that girls were not pregnant when they were . . . An applicant labeled as pregnant was told by the personnel director that she was not qualified, or that all the positions were taken . . . For girls who managed to slip by . . . supervisors made life difficult for them when they realized the girls were pregnant. They would do things like put them on the night shift—which is completely illegal under Mexican labor law.

In 1998, a

Los Angeles Times

article quoted Dr. Moreno, who claimed that

she watched a manager at Matsushita caress the buttocks of each woman he passed on a welding assembly line. A married mother of six was told to sleep with her boss or lose her job, Moreno said. When she complained, he accused her of stealing. The woman got severance pay only after Moreno made her the cause celebre of a radio campaign . . .

As you see, even Dr. Moreno made no mention of any “Miss Maquiladora” modeling contest. And from the present millennium I could discover no allegations of any nature against Matsushita, excepting only the following item from the

San Diego Union,

datelined 2002:

In Tijuana, the top producers of highest-risk waste are mainly Asia-based companies, including South Korea’s Samsung, Japan’s Matsushita, and Taiwan’s Merry Tech.

By then I was sure that Matsushita was a very nice company, really a very sweet company. To prove it, Terrie wired up Perla one last time, and we set out for Matsushita, determined to ascertain the existence or nonexistence of a workforce in white tennis shoes and miniskirts, eighteen to twenty-five, not fat.

Following Perla’s directions (over our two working days she seemed to know the whereabouts of every

maquiladora

on earth), we wound up the hill, then back down past Robinson and Robinson, into the valley of dirt and factory-cubes. The first time Perla went into Matsushita (while Terrie and I waited outside another white stucco wall with fenced inserts; she was rereading

A Moveable Feast

and I was worrying about what to do if Perla got in trouble), the dear old button camera didn’t record a thing. We went to a fast-food restaurant and I bought giant sodas for the members of my spy team while they retired to the ladies’ room to rewire Perla and make more practice videos; in the end they decided to have her carry the digital video receiver in her little purse, prestidigitating the wire into the wire of her cell phone; and this device raised our industrial espionage to an entirely new level. Back to Matsushita she went, returning almost immediately, cheerily swinging her arm, her hair blowing in the breeze, so the next morning early, when

maquiladoras

hired, we wired her up again and sped off to Matsushita, parking not quite in front, since we were discreet individuals, and then for one hour, eleven minutes and forty-six seconds, Terrie reread more of

A Moveable Feast

while I entertained myself with the spymaster’s stress of wondering whether Perla’s batteries would run out. For variety’s sake I sometimes gazed at an installation of barred windows within a courtyard of cheerful green shrubs whose fortifications consisted of barred gate-segments in tracks which slid apart or together by electronic command; the climax came near the end of the hour, when a corrugated cardboard truck entered. This barred gate kept me from learning dreary secrets. Were they secrets only of sickness and death? Or were they secrets which might have made me illicitly rich, *** TRADE SECRETS *** I mean? Answering that was what button cameras were for.

Across the street from that long white regularly windowed factoryscape, a man stood beside a huge white truck which pumped its cargo into a well beneath the street beside the entrance to a

maquiladora

from which four tall and one slightly shorter white cylindrical tanks stood. Some time after I took his photograph, he yawningly knocked the truck with a mallet to see how much of the chemical remained, then put on a mask. It was almost hilarious. The man with the black cough, the two decontamination men who ate their sandwiches in the lead dust of Metales y Derivados, and now him, what did they all really think? Did they not believe in the danger or did they try not to think because they could see no other choice or did they not care?