Imperial (199 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

“According to the Federal census of 1920 . . .”—Imperial Valley Directory (1926), p. 5r.

“The metropolis of the Imperial Valley”—

Out West

, vol. XXIII, no. 12, January 1905, unnumbered page.

Comparison of business buildings in Imperial and El Centro—Imperial Valley Directory (1926), pp. 50, 47.

Numerical comparisons of the buildings of Brawley, Calexico, El Centro, Holtville, Imperial in 1912—Imperial Valley Directory (1912), pp. vii-xiii.

Description of the Queen City Independent Band—ICHSPM photograph, cat. #P92.70.

Population of Imperial—Tout,

The First Thirty Years

, p. 270, gives the following figures: 1904 pop., 900; 1910 and 1920, 1800, 1920; 1930, 2000. These differ slightly from Berlo, “Population History Compilation,” pp. 266-67: 1910, 1,257; 1920, 1,885; 1930, 1,943; 1940, 1,493; 1950, 1,759; 1960, 2,658; 1970, 3,271; 1980, 3,210; 1990, 4,113; 1998, 7,475. It was not until later in the fifties that the city began to grow, nearly doubling by 1970, and more than doubling again by the century’s end.

Tale of El Centro, Holt and C. A. Barker—Mount Signal website.

Rockwood’s objections to Imperial—Farr, pp. 125-26 (C. R. Rockwood, “Early History of Imperial County”).

66. Their Needs Are Even More Easily Satisfied (1893 -1927)

Epigraph: “It is an interesting commentary. . .”—Paul S. Taylor,

Mexican Labor in the United States: Migration Statistics. IV

, p. 35.

Chinese and Japanese history in Riverside, 1900-1920—The Great Basin Foundation Center for Anthropological Research, vol. 1, Chronology sec.

Japanese in Imperial Valley, 1904, 1908—Street,

Beasts of the Field

, p. 475.

“Lemons which made the size known as 300s . . .”—

California Cultivator

, vol. XXIII, no. 19 (November 11, 1904), p. 467 (“News Notes of the Pacific Coast”).

“The general persistency with which the Japanese are breaking into many industries . . .”—Asiatic Exclusion League, p. 11 (1907).

Japanese as 42% of California farmworkers, 1909—Street, op. cit., pp. 409, 486.

Figures on Japanese ownership and leases, 1912—California Board of Agriculture, 1918. One Chinese and three Japanese business establishments are depicted in the Fire Department’s 1906

Souvenir of the City of Riverside

, which contains mostly photographs of properties owned by people with such names as Anderson or Wardrobe. —Riverside Fire Department, pp. 49, 52, 65.

Masako et al.—ICHSPM, photo #P85.15.9.7.

Japanese collective bargaining—Street, op. cit., pp. 415-23, 432-70.

“The Jap laborers . . .”—

California Cultivator

, vol. XXVII, no. 1 (July 5, 1906), p. 2 (“News of Country Life in the Golden West”).

Letter from Edwin A. Meserve—Asiatic Exclusion League, unnumbered page (prob. p. 1), “Views of Men Seeking Public Suffrage, Who Present Correctly Attitude of California,” letter of August 5, 1910.

Letter from William Kent—Ibid., p. 5.

“Is the World Going to Starve?”—

California Cultivator and Livestock and Dairy Journal

, vol. LIV, no. 3 (January 17, 1920), p. 1.

The Gentlemen’s Agreement: The Great Basin Foundation Center for Anthropological Research reports that by 1920, “Japanese gradually begin leaving the citrus industry, and are replaced by Mexican immigrant agricultural workers.”

Airplane-smuggling of 1927—N.A.R.A.L. Record Group 36. Records of the U.S. Customs Service. Communication from William Carr, the Southern California Immigration Director.

“But whereas the Chinese were good losers . . .”—Hunt, p. 422.

67. Negroes and Mexicans for Cotton (1901 -1930)

Epigraph: “. . . the Latin-American does not propose that any one shall know him . . .”—

Fresno Morning Republican

, Sunday, March 21, 1920, p. 5B (speech delivered to night school class, reported by Captain A. P. Harris).

“The question of competent labor has become a most serious proposition to the fruit-growers of California . . .”—

Western Fruit-Grower

, vol. 13, no. 4 (April 1903), p. 8.

Footnote: The “Nigger-head” cactus—

California Cultivator

, vol. XXIII, no. 8 (August 19, 1904), p. 171 (“Denizens of the Desert”).

Arrival of “basic strata,” Swiss, colored people, Muslims and Hindus—Farr, pp. 280-81 (Edgar F. Howe).

“Cotton has been especially valuable . . .”—Farr, p. 190.

“While the history of Chinese immigration . . .”—Hunt, p. 370.

“Some difficulty has been experienced in securing labor . . .”—Farr, p. 190 (Walter E. Packard, “Agriculture”).

“Labor was supplied by the Indians . . .”—Laflin,

Coachella Valley

.

Mexican laborers in Inland Empire citrus, 1914-19, 1973—Wagner, p. 55 (exact numbers: 2,317 to 7,004).

“Reliable and efficient men,” etc.—Packard, pp. 15-16. In 1909, the

Desert Farmer

advises: “Mexican labor can be secured and is highly satisfactory in this work as in Texas. Planters in Imperial Valley can afford to pay at least a dollar per hundred pounds . . .” (

Desert Farmer

, Imperial Valley, May 1909, p. 89 [Joseph R. Loftus, “The Cotton Culture in Imperial Valley”].)

In the century’s second and third decades, acreages of sugar beets and cotton explode. And you’ll be thrilled to know that sugar beet samples from the Imperial Valley “resulted in proving 18.3 per cent sugar in the beet and 82.6 purity.” (UC Berkeley. Bancroft Library. Paul S. Taylor papers. Carton 5. Folder 5:41: “Perspectives on Mexican-Americans, Final Draft w/Footnotes, 1973.” Typescript, “Perspectives on Mexican-Americans,” p. 4.) Imperial cotton will be just as fine; soon they’ll be calling it “the white gold.” Hand labor will be just the ticket for those crops! Whose hands should labor? I wonder. Taylor sees the employment of Mexicans in the sugar beet and cotton industries as setting the stage for them as migrant workers in other large-scale agriculture. “For most Mexican-Americans this meant northward migration to the beet fields in the spring, and southward migration to winter quarters—even return to Mexico—in the fall.”

“Camp conditions in 1914 were unspeakably bad . . .”

—Fresno Morning Republican

, Sunday, March 21, 1920, p. 9B, Arthur L. Johnson, Director, Fresno-Bakersfield Offices, State Commission of Immigration and Housing of California, address to San Joaquin Valley Federation of Women’s Clubs, Porterville, California, March 11, 1920. By 1920, of course, life is much better. “The community camp is a system whereby a number of farmers, by clubbing together, erect a camp at a spot convenient to all, which serves as a labor center from which workers go out to adjoining farms when needed . . . The problem of part-time work is solved; the owner of a small orchard does not have to worry concerning what he should do with his workers on days when his fruit may not have ripened enough for picking . . .We must assist in the task of taking the raw immigrant and making a good loyal American citizen out of him . . . In Bakersfield, the city employs a home teacher who holds a class for Mexican women three afternoons a week in an empty box car at the Southern Pacific camp, and in addition has a class for immigrant men two evenings a week, where the men can come to learn after their day’s work is done.” I can’t help believing in people.

“The emergency rules will allow farm workers to seek at least five minutes . . .”—

Sacramento Bee

, Friday, August 5, 2005, p. B6 (“Opinion” section, “Some heat relief: Governor alone can’t protect farm workers”).

So who are the farmers and who will they be? On the old Imperial County Assessor’s maps, here are some common names of property owners: Shank, Flint, Waldron, Lewis, Kidd, Allan, Moore, Fristoe, Helsinki, Ledermann, Gee, Lister, Beezler, Bray, not to mention Clark, of course. Here also are Aviles, Singh and Matsumoto; but in Imperial County in 1910, almost 1,100 out of 1,300-odd farmers were native-born whites.

Death records show a different preponderance of names: Contreras, Corrales, Calderon, Castro, Chalaco (for of course I was looking for Clark); Cordova, infant of Tiburcio, deceased Dec. 31, 1945, and properly recorded in certificate number 8, Book 12.

Well, they must not have been farmers, then. They must have been laborers. Paul S. Taylor asserts that even Asian immigrants were able to buy farms in California, but . . . “times had changed greatly when the twentieth century Mexicans arrived. Not only was there no agricultural ladder for them to ascend; the effect of their ready availability to landowners was to check further widespread distribution of ownership, and so to contribute further to the decline of the ‘family farm.’ ”

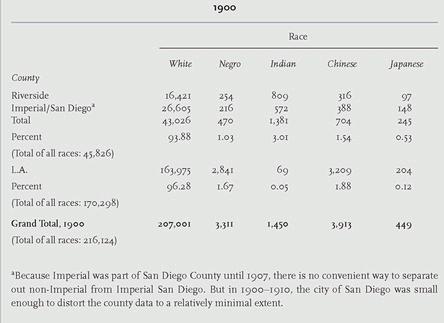

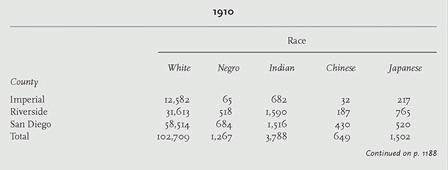

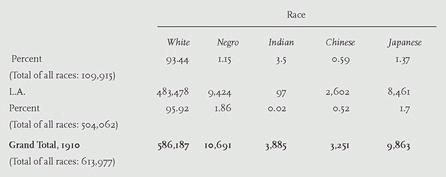

White and Colored Population in the Entity called Imperial

and in Los Angeles County, 1900 and 1910

[

Note: Mexicans were considered white. The 1930 census for the first time introduced category of Mexican-ness.

]

Source:

California Board of Agriculture, 1918, pp. 36-37 (white and colored population by counties, 1900 and 1910).

T. H. Watkins in his history of the Great Depression asserts that “by the 1930s” Mexican-Americans “dominated California’s traditional migrant labor pool,” Chinese, Hindus, Japanese, Koreans and Filipinos having come and gone. But a regional geography from 1957 reports that “labor consists of Mexicans, Orientals, Negroes, and migrant Caucasians under the direction of Caucasian foremen.” The bountiful continent is ours, state on state, and territory on territory, to the waves of the Pacific sea.

Sources to foregoing inset:

Number of native-born white farmers in Imperial County, 1910 (1,077 out of 1,322)—California Board of Agriculture, 1918, p. 43, Table XIII (other relevant figures: L.A., 5,682 out of 7,919; Riverside, 2,044 out of 2,688; San Diego, 1,591 out of 2,298).

“Times had changed greatly when the twentieth century Mexicans arrived . . .”—UC Berkeley. Bancroft Library. Paul S. Taylor papers. Carton 5. Folder 5:41: “Perspectives on Mexican-Americans, Final Draft w/Footnotes, 1973.” Typescript, “Perspectives on Mexican-Americans,” p. 5.

T. H. Watkins on Mexican-Americans’ place in California migrant agriculture—Op. cit., p. 395.

“Labor consists of Mexicans, Orientals, Negroes . . .”—Griffin and Young, p. 174.

68. Mexicans Getting Ugly (1911 -1926)

Epigraph: “Say, old boy, there’s something doing in Mexico . . .”—Grey, p. 25.

“First woman JUROR in State of California”—ICHSPM photograph, cat. #P85.51 (credit: N. J. Metz; the court was Judge Cole’s).

The flight of the rancher from Nuevo León—Hart, p. 61.

“The Valley was uneasy on account of depredations . . .”—Tout,

The First Thirty Years

, p. 198 (files of

Imperial Valley Press and Farmer

).

“The boss will be leery . . .”—

I.W.W. Songs

, p. 41 (Richard Brazier, “When You Wear That Button”).