Imperial (50 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

In 1903 his hardware store receives brief mention in the newspaper. I see that he owns a hundred and seventy-five acres of Imperial Water Company No. 1. And the crop acreage of the Imperial Valley quadruples, from twenty-five thousand to a hundred thousand acres!

His advertisement is larger now. I see that he is offering ellwood and kokomo steel wite fences, barbed wire, hogs, sheep, cattle, poultry. Sometimes it changes borders. He soon has a harness department, a paint department offering white lead, oils, glass, asbestos, cold water paint.

At the end of that year, after a tenure of twelve months, Margaret Clark resigns as postmistress, perhaps because she will soon become Mrs. Archie Priest. The marriage will take place next April; in the write-up, the bride’s brother will be referred to as

our popular businessman, Wilber Clark.

Meanwhile, on 11 September 1903, canny Wilber Clark sells land to the county of San Diego.

On 12 April 1904, an auction of lots is held in Imperial. Under a tent-awning men in hats and overalls sit on long benches. Other people stand, including one lady in a white blouse and a long, long dress; they must be purchasers, for we see them approaching the table where three men sit facing us and one black-clad lady in a remarkable hat sits in profile; perhaps she’s the stenographer, although it’s early in the century to count on that. A man in black and white stands, resting his white sleeve on the table; he’s the auctioneer. Behind him an enlarged map of

PART OF TOWNSITE OF IMPERIAL

tempts us all. So we approach him one by one, to buy our American dream. The seller: George Chaffey’s California Development Company, which controls water rights to these public domain lands. The water supply this year as last year remains irregular enough to cost us many a tight-clenched dime, but next year Rockwood and Chaffey will surely unkink the Imperial Canal. One of the citizens in that line may be Wilber Clark—unless, of course, he’s bought his lot long since. This is the year we find him proving to be by the standards of Imperial an almost fanatical participant in the political process: He signs a petition to incorporate Imperial as a city of the sixth class. (In those days, cities were ranked by population size.)

Thirty-seven votes were cast,

reports Otis B. Tout,

although the town had 800 inhabitants.

San Diego accordingly disqualifies the result. A second attempt succeeds three months later. Otis B. Tout doesn’t tell us, but I’d wager my hammer and nails that Wilber Clark has signed that petition, too.

We can count on his sister to accompany him on civic and mercantile adventures; the very next month she’ll buy land from the Imperial Town Company—twice. Beloved of the Ministry of Capital, she’s not only a true believer but a woman of means.

IRRIGATION’S POWER

Two months later, the Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries happens by Imperial. Since in 1904 there is only one game in town, we know where he sleeps: the Hotel Imperial, which beginning this year is no longer a conglomeration of tents but an

edifice

whose colonnade supports a graceful skirt of wood above the balcony, which runs around all four sides, and beneath which three ladies in long white bell-skirts recline in rocking chairs while a farmer-type gentleman in a hat and overalls stands behind them at the double door, with his hand in his pocket; meanwhile, a second gentleman in a suit, who for all I know could be Hugo de Vries himself, seeing that the dates of his visit and this photograph match, rocks in his own world somewhat leftward of the ladies; this scene, like everything else in Imperial, has been divinely framed by glaring whiteness above, around and below. Presently Hugo de Vries arises from his rocking chair and takes a stroll past Wilber Clark’s hardware store. Noting the wide, wide streets, which make the teeming thoroughfares of Chicago seem like alleyways, he concludes, I know not whether with ingenuous admiration or Old World irony:

Like all cities in the west, Imperial has been designed on the chance that it will one day be the largest city of America.

In 1905, when the first aircraft, a skeletal, blocky biplane, lands at Imperial town,

freight receipts at Imperial, $70,000 for the month of May, placed that station third in size on the S.P. western lines. Los Angeles is first and San Pedro is second.

Imperial has awakened now! In a darkening, vignetted, badly mounted old photograph datelined simply “Imperial” we see a horse and buggy, a hitching post, an arcade of sorts roofed with wavy metal siding; within its shade stands a line of men and ladies in their light-colored best, the latters’ dresses ankle length; I see a boy, too, in a little cowboy hat; the dark door behind them is open; the store window reads VARNEY BROTHERS DRY GOODS

.

Perhaps Wilber Clark’s little store looked pretty shabby compared to that.

We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

Next year our neighbor Mr. McKim will already possess twenty-five hundred hogs on his ranch east of Imperial.

THE DESERT DISAPPEARS.

To be sure,

Sharp’s Heading is a cheap wooden structure and has been for some time in imminent danger of washing out,

but never mind that; we trust our engineers here in Imperial! When the Salton Sea accident occurs, I’d be surprised if Wilber Clark did not appear among the active citizens who dig and dynamite the New River in efforts to save Calexico, Seeley, Imperial, El Centro.

By now we’ve already raised several homes in Heber. Brawley shows off fifty houses, a hotel and of course a church; Mecca boasts its first school and an experimental date station; the population of the Imperial Valley has increased from two to seven thousand; fifty thousand acres now lie under cultivation! In the Coachella Valley the first Japanese arrive. William E. Smythe is on the verge of publishing his triumphalist revision of

The Conquest of Arid America.

To quote de Vries again:

I was particularly surprised at the speed with which all kinds of weeds and European plants spread under the influence of irrigation . . . Soon the endemic flora will have been displaced largely by these foreigners.

THE SUBMARINERS

Again, who was Wilber Clark?

An old man in Campo once told me of the turn-of-the-century Imperial sanctum called the

submarine:

One erected a tent inside one’s house and hung soaking wet sheets on it. The water ran down the tent and condensed on the inner walls of the house. Not everyone could afford to do that, the old man said.

79

To me, these conditions sound ghastly. Who was Wilber Clark, to give up the orange groves of Los Angeles for

that

? What were his motivations? Did he long so much for Emersonian self-sufficiency that discomfort was no object? Or did he simply aspire to be said of:

He sold out at a fancy price?

He certainly could aspire to making any number of silver dimes.

Cattle and hogs are going forward to market now on nearly every train, says the

Imperial Press.

This judge’s son, buyer and seller of land, retail capitalist and possible automobile owner, could not have been desperate. He must have been something else.

VISION OF A HARDWARE STORE

Raymond Chandler, whose hatred for the hypocrisy and corruption of America is symbolized in and localized by Los Angeles, puts these words in the mouth of a millionaire:

There’s a peculiar thing about money . . . In large quantities it tends to have a life of its own, even a conscience of its own.

Chandler musters no admiration for that conscience. He hates the magnates; despising the cheap grifters and the cops who beat suspects, he sneers at the blondes who laugh too loudly; he smells out dishonesty everywhere, so it’s not surprising that the small-town ideals espoused in American Imperial under-impress him. Here is how he imagines himself into Wilber Clark’s life:

I would have stayed in the town where I was born,

which my hero declined to do,

and worked in the hardware store,

which he certainly did,

and married the boss’s daughter and had five kids and read them the funny paper on Sunday morning and smacked their heads when they got out of line . . . I might have even got rich—small-town rich, an eight-room house, . . . chicken every Sunday, . . . a wife with a cast iron permanent and me with a brain like a sack of Portland cement.

For Chandler, the hardware store symbolized inability to escape one’s narrow origins. For Clark, it was the frontier itself.

What is Imperial to you? I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

THE AMERICAN DREAM

In 1907, a man whose name the County Recorder spells Wilbur Clark buys land from Harry Cross; and in the same month, he buys a new lot from the Imperial Land (not Town) Company.

We presently find him in Calexico, in the company of Elizabeth F., whom he must have married out of the county, since the marriage isn’t recorded in its books; and in that city the couple establish a new hardware store. (The first permanent structure in Calexico was an adobe; the rest being tents or else ramadas such as Harold Bell Wright wrote

The Winning of Barbara Worth

in.) I wish him joy in his marriage, and I hope that he takes his bride to Mexicali at least once. Why shouldn’t they feel at home there? It’s not as if they’ve left the Salton Trough.

A

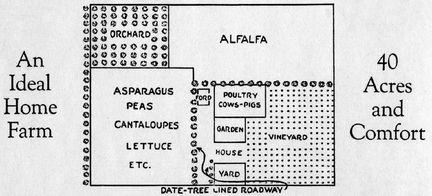

N ideal home farm in Imperial valley is a 40-acre tract. Rich soil, abundance of water and the possibilities of whole-year culture and a wide variety of products combine to make the small farm the best for practical results.

The foregoing diagram shows in a graphic way how such a farm may be divided. It provides a central location for the home, and the things immediately pertaining to it. Not only is diversification of crop suggested but the possibility of their rotation is provided. The alfalfa field and the vegetable acreage can be rotated as desired. The only permanent plantings are the orchard and vineyard.

Alfalfa grows in such abundance that dairying is a profitable venture on the small farm. Through it cream checks are kept coming to the farmer with monthly regularity throughout the whole year. Poultry and hogs go with the combination to make it one of an appealing character. The vegetable plots offer a wide latitude of choice.

A factor not to be overlooked favoring the 40-acre farm is the problem of labor. Planned as suggested in the foregoing, the average farmer and his family can care for crops without help. This gives a degree of independence not otherwise possible.

I don’t suppose there’s much to buy in Mexicali in 1907; but once the Colorado is finally diverted back into its old bed, entrepreneurs begin to rebuild Southside. Do the Clarks ever find time, as so many of the Mexican field workers I have interviewed in Imperial County never did, to visit the new Salton Sea? I can almost see them trying on a holiday mood as soon as they’ve set foot on the other side of the ditch; the weariness of their labor and their money worries briefly depart them when a Mexican beckons them through a tall palisade and into an adobe house which is the same grey as the dirt in this old photo I’m now dreaming over in the Archivo Histórico del Municipio de Mexicali; the house stands steep-roofed beside the steep-roofed skeleton of a corral’s framework; I see a horse and buggy off to the right, the horse’s silhouette shockingly skinny. Soon they come out with his arm around her; he has bought her a pretty Mexican blanket.

Who was she? I perceive little in common between her and Barbara Worth, whom a historian describes as

the “Imperial Daughter” of the Imperial Valley: a tall, outdoorsy Girl of the Golden West who speaks fluent Spanish and spends much of her time riding the desert on horseback.

On the subject of Imperial Daughters, Judge Farr writes:

Most of these are country born and bred, with an ancestry of sturdy farmers of which they have been proud to boast . . . plain women with big, noble souls, ready for any honorable and worthy task that was set before them.

Elizabeth F.’s maiden name was Schultz. Census data indicate her to be a German immigrant, born in about 1874, who had entered the United States aged eleven, in the year when Tecate was founded, the first store sprang up in Indio, and the first Chinatown was torched in Riverside. I therefore suppose that all her life she will speak English with a slight German accent. Perhaps this charms her husband, who may himself retain a midwestern drawl. In 1907 he is forty-six and she is thirty-three. Lucky Wilber Clark!

On March 15 of the previous year, Wilber Clark sold unspecified real estate to G. W. McCollum, a rival hardware store man. I am guessing, therefore, that what Clark conveyed to him was the business in Calexico. Perhaps it is this very sale which affords sufficient capital to build a dream at last.

Indeed, the Clarks eventually settle on the

now greatly improved

Wilfrieda Ranch, or Wilfreds Ranch, a hundred and seventy-one acres in area. The year of their land patent is 1911. They pay in full and in cash.