Imperial (63 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

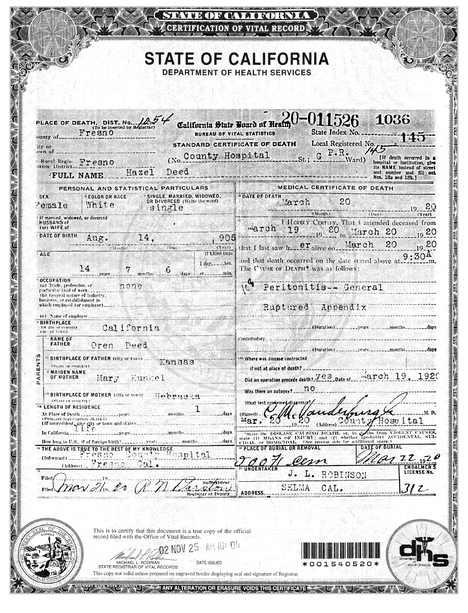

I searched the

Fresno Morning Republican

for her obituary. Well, probably the paper had already gone to press by the time she died. On Sunday, the “Commercial News” section reported this datum from the San Francisco market:

Eggplant, Imperial Valley, nominal.

On Monday, Imperial Hazel Deed was buried. (The undertaker was J. L. Robinson of Selma, embalmer’s license number #312.) On Tuesday, the state of Washington ratified female suffrage. Every day there was more commercial news, but the child who had already been shucked of her grandiose name continued to be ignored in death. For instance, on Saturday the twenty-seventh, the citrus column announced that in Boston, oranges were up but the lemon market was unchanged. In Cleveland six cars of oranges were sold. In New York the market was steady on lemons and tangerines. Then an advertisement advised us to PHONE 3700 FOR THESE SPECIALS TODAY, LETTUCE, namely Fine Fancy Imperial Valley lettuce, was on sale for fifteen cents per two heads. April thirtieth was going to be Raisin Day in Fresno . . .

Chapter 56

STOLID OF FACE AND LANGUID (1901-2003)

Mexican women turned their tortillas on improvised griddles; Indian women, stolid of face and languid, did their share, fed the bucks on the levee and took care of their naked youngsters who huddled like frightened rabbits under the mesquites.

—Otis B. Tout, 1928

I

f Imperial County “went wrong” somewhere, transforming “potentially . . . the most valuable land in the United States” into the poorest county in California,

how

did it go wrong? I asked an official of the Employment Development Department in El Centro this question, and he said that he hadn’t been working there very long, so he didn’t know. A plausible Marxist-Leninist answer might be that many homesteaders became rich enough (or that the Ministry of Capital started rich enough) to hire poor people to work their land. Holdings enlarged themselves beyond the statutory limits of the 1902 Reclamation Act, therefore requiring ever more legal and illegal laborers for the harvest, so that the county’s per capita income went down once those laborers began to get counted. They are certainly

under

counted. One study begins by asserting that migrant farmworkers are

by any reckoning . . . the poorest, the least represented and the most abused class of working people in the United States.

As for Hispanic workers in particular, after Mexico lost the war of 1846-47,

throughout much of the area, Mexican Americans were reduced to the status of menial laborers serving white masters. This is a fair description of the state of affairs that exists in the border region today.

In 2003, Mr. Philip Ricker of Holtville writes this letter to the editor:

The great percentage of farm workers are green carders from Mexico who are seasonal . . .

They

cause the Valley to have the highest unemployment and poverty rating in the state. They contribute little to the economy of the Valley, even though the farmers hype that they do . . .

Indeed, if you read

The Conquest of Arid America,

or

The Winning of Barbara Worth,

you may believe that white farmers did everything on their democratically small homesteads. When the Barbara Worth Hotel opened in El Centro on 8 May 1915, everyone got to see the Imperial Valley’s beginnings depicted in oils, one or two of

which will stand for the ages, no doubt,

never mind that the Barbara Worth burned to ashes in 1962. Anyhow, here is “Labor”:

Picture a man in desert garb, his throat open to the sun and wind, his arms bare to the elbows—yes, just such a man you will see, a hundred times every day in Imperial Valley—the laborer. Well knit muscles, strong in body, sturdy in character, the laborer bears the load of work faithfully.

In

The Winning of Barbara Worth,

his name is Pat.

In Mexican Imperial, his name is José or Manuel; and in the

ejidos,

he has truly built and labored for himself. In American Imperial, his name is Pat, or Wilber Clark, if you like, but he has many helpers even though

The Winning of Barbara Worth

would have us believe that

he made a success through his own efforts.

It is bemusing, and ultimately chilling, to watch how American Imperial uses up one race after another for her ends, and then they’re

gone,

because

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

Mexican labor has lasted the longest, a good century now; and as I write this sentence on a muggy spring day in 2006 I remember the title of a movie that came out recently: “A Day Without a Mexican.” What if all the gardeners, babysitters and waitresses refused to appear? In 1886, the

Rural Californian

inquires:

Suppose, for instance, that every Chinaman is driven out of the Santa Ana Valley next week, who is to take his place in the field, in the laundry, and in the kitchen?

In 2004 I asked Alice Woodside (born in Imperial County in the early 1940s) whether she recollected any whites who worked their own farms. She replied:

You know, maybe when I was a kid maybe there were a few leftovers, people who lived in very dilapidated homes, very poor, where there was still white labor. I was unaware if they had money or if they didn’t, because nobody did. There was such a population of people who were pretty impoverished, I would say, but I didn’t even look at it that way . . .

Chapter 57

THE DAYS OF LUPE VÁSQUEZ (2003)

The Imperial Valley’s fertile soil and mild climate allow farmers to enjoy year-round planting, cultivation and harvest.

—Imperial Irrigation District, fact sheet on agriculture, 2001

W

hen I wake up in the morning I don’t feel like getting up. It’s too cold and I’m tired from the day before and the first thing that comes into my head is it’s gonna be a long day. If there’s ice, I’m not gonna get paid for that time. It sucks. At least I’ll get paid something. Most of these places pay every day.

When you take a sandwich, they say,

Don’t get up, honey, I’ll buy a torta.

They make fun of you. They say,

Don’t get up, honey,

when you break out a sandwich. They know damn well your wife’s not gonna get up. Why should she get up at three-thirty in the morning?

And the sex, there’s no sex. They make fun of it. They say, turn your back on your wife. Eat, shower,

nada.

I don’t worry about it, ’cause Sancho does it. She’s in Sancho’s hands. That’s what they say. You might as well laugh and make fun. Day goes easier.

At three-thirty I get up, drink coffee, get dressed, sometimes eat breakfast. I’ll drink a beer in the morning, one or two. There’s always this guy selling beer at Donut Avenue, at a dollar a beer. He has slanted eyes, but he’s Mexican. They call him Chino. He’s been caught but he just sells his beer and goes on home. He’s a smart old man.

From my

colonia

it’s a twenty-minute walk to where I catch the taxi and another ten-minute walk when I get here in Calexico at four-thirty. The first thing I try to do is get myself in a good crew where they’re gonna pay me. I decide on what kinda work I wanna do. I pick the easiest, and for me the easiest is broccoli, because I don’t wanna crouch.

99

Some people say that lettuce is easier, but you crouch and get wet. With broccoli you get wet, you get cold, but once the sun is out, you warm up. On Donut Avenue some guy’s yelling,

Broccoli, broccoli! I’ll pay you every day!

This guy is hustling for the foreman. I watch for that guy.

In June, there’s cantaloupes and watermelons. There’s tomatoes. In July, August, September, there’s no work, hardly none, ’cause it’s too hot. In October they start thinning out the broccoli fields, start planting.

If you work for a crew for ten straight days, most of the guys will be the same. Well, maybe not most, but some, I’ll know their faces. Lot of times the word will be passed: Don’t work for that asshole; he yells too much.

Sometimes there’ll be a bus that’ll take you over there, and sometimes there’ll be vehicles that’ll charge you two dollars or three dollars for a ride. So I prefer the bus.

You never see the Border Patrol.

When you get to the field and the ice hasn’t melted, you can wait inside, but a lot of people make bonfires. You can play cards, joke around. Some might smoke their joint, shoot their heroin. A lot of the girls are used to dick-tease the guys, but most guys never get some. The guys really think they’re gonna get some! It used to be, years ago, that the foreman used to get pussy: If you don’t gimme some, you won’t get no work tomorrow. But even now, some of them just get to take it easy, just write down the employees’ names and jobs in exchange for giving pussy. For the guys, what they do doesn’t matter. For the other women, some of them get jealous. I never even try. I mean, women, it doesn’t matter what race and what creed, they all have the same spirit of vengeance against you.

Most of the time, the ice will disappear by about nine-thirty. But sometimes there’s that black ice and you wait till noon. You don’t get paid for that time. That’s just another way they rob us. We work till dark. I’ve worked places where they shine lights on the field so we can keep working at night. That’s in December, January, February. But when I’ve been working all the days of one of those months, usually there’s ice only for about a week.

When there’s no ice, you start working as soon as you can see.

The foreman says,

Muchachitos,

little kids, let’s go! Or, come on, ladies! Just like the way they talk to us in the military. Then everybody gets their tool, a hoe or knife or whatever. And then I’m feeling terrible, horrible, like you don’t wanna start.

It’s worst when you’re on your last couple of hours. The last hour is always the worst. The foreman understands that everyone’s tired. Most of the time he won’t say nothin’, ’cause by then the job’s almost done. A few will grab a hoe and help you out for a little while.

For an eight-hour job, it’s forty-five bucks. When I first started, in the early seventies, I used to make about seventeen dollars a day. Two-fifty an hour times eight hours is what?

100

With taxes you’d take home about seventeen, eighteen bucks. I’d say the work’s the same now; it’s the same.

101

Maybe the foremen don’t hurry you up and treat you as bad as they used to. We were scared, you know. We had to hurry up. For the foremen, money is more important to them than their own people. They gotta kiss ass, and the way they do that is by making us work harder.

They usually let us off where the railroad is, right back by that seafood place on Imperial Avenue, I think on Second Street.

A lot of times, after work you drink a beer with two or three work buddies. Not friends, not buddies, just work buddies. I’m in the mood to go home right away. Once in awhile I’ll do it, but when I was younger and single I used to party all night, screw whores all night and come to work broke.

In January it’s broccoli, lettuce, asparagus, and caulifower. In February it’s the same, and then also carrots in February, March, April. I never done carrots. In March it’s all lettuce, just lettuce left and a few broccoli. It’ll end by the end of this month.

In April there’s hardly anything. It’s kinda like a break. A lot of people have no work. All that’s been done in this month is the weeding of the cantaloupes, of the watermelons, and they’re weeding it, they’re cleaning it, they’re uncovering it from the plastic for the freezing season.

May’s onions, lots of onions. Everyone’s talking onions. They pay you piecework, sixty, seventy cents a sack. It takes me about five minutes, three minutes a sack. And they pay on how fast you top. At the beginning of the topping season, the ground is still muddy and sticky, so it takes a long time to shake the mud out of it. Later on, when the land is dry, it’s faster. When the land is sandy, it’s loose.

In May and June there’s also cauliflower and tomatoes. In June you have cantaloupes, watermelons, tomatoes, bell peppers. Bell peppers, you just pick ’em off the plant, fill the basket, carry it to the end of the row. Now they say it’s different; I don’t know. They say they have a machine. I don’t know if they pour it in a truck or boxes, I don’t know.

There’s hardly anything in July.

102

They’re still the last of the cantaloupes, maybe the last of the watermelons. People collect unemployment. A lot of people go up north to the Salinas Valley to do lettuce, or to the Coachella Valley to do grapes.

In August it’s dead, Bill. Totally dead. There ain’t nothin’. You don’t hardly see no soul. I just stay inside, kick back, drink a lot of beer.