Imperial (64 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

And in September there’s no crops, Bill. It’s dead. They start planting the lettuce and broccoli and stuff on the ranches, but the farming is asleep that month. In October there’s no harvesting. In November they start harvesting some broccoli, some lettuce.

December, that’s when all the work starts. Lettuce, cauliflower, asparagus, some spinach, some cabbage. Corn . . .

God, so that’s my life.

Chapter 58

“LUPE IS LUCKIER” The Days of José López from Jalisco (2003)

The spectacular incidents connected with the reclamation of the desert and with the subduing of the turbulent Colorado have given Imperial Valley a charm of romance that is hard to equal. A history of agriculture under such conditions must be a story of human interest as well as a statistical record of development . . .

—Judge F. C. Farr, 1918

I

usually wake up between five and six. I just don’t get up real quickly, because those abandoned buildings, a lot of ’em are used by addicts to go smoke and do whatever they do, so I wait until they’re done doing their thing, but all the same I got to get up early. Myself, been a few months since I smoked any coke. In Mexicali it’s hard to get rock. What you have to do is buy the concentrated stuff and make your own rock. Well, anyways, that’s one of the reasons I get up early, before the police come.

There are usually other people there. Sometimes I go to sleep alone and wake up with other people. We’re almost all men.

When I go to sleep, I take with me a gallon of tap water. You gotta go ask somebody you see watering their garden. Some people don’t even wanna give you water, man. Some people are just mean. So I bring it to the abandoned house at night, so I can wash up in the morning, so I don’t have to go out and then come back again and maybe get caught by the police. I go to the public showers once or twice a week: thirty-three pesos. The other days I just shower from a jug in an abandoned house. So I get up, take a shower, take a leak, whatever. In restaurants I get napkins, whatever, to wipe myself. Sometimes I have to use a paper bag.

So I walk toward the border, stop over at a stand over there by the taxis, and if I have the funds, I get a coffee, a pastry maybe. Then I sit down right here by the wall. I try to be here around seven, seven-thirty. Sometimes I walk and sit over at that bench over there if this gate is closed. They open this gate at eight in the morning. Then I watch for tourists, people who might need some help, and try to hit ’em up. I say: Good morning. Can I help you? Do you need a taxicab? If they say no, I still insist: Are you looking for a good pharmacy even if you lost your prescription? I’m friends with the head pharmacist. Or do you want to eat good, or shop good? Do you want to know where there’s a shopping mall just like in your country? I just try to convince ’em! I have about two minutes before their voice changes and the way they say no changes; then it’s hopeless.

For taking ’em to a taxi, opening the door for ’em, and telling the driver where they want to go, I might get more; I might get less. They might gimme a dollar, two dollars . . . My biggest tip for escorting a couple to a cab was twenty dollars. They were middle-aged people, really nice.

That’s what I do from seven A.M. to eight P.M. The most I’ve made during one day is close to two hundred dollars. That happens rarely, maybe five times a year. And the least, some days I haven’t even made a single peso. On an average day, I make, say, twenty dollars.

I try to stick to a fare, a price, so as soon as I start workin’ for ’em, I tell ’em I’m expecting twenty dollars, and I usually get it. But sometimes they don’t pay. Then, since I done my work, my part of the deal, for them to say, I’m payin’ you nothing, that gets me mad. But that’s pretty rare.

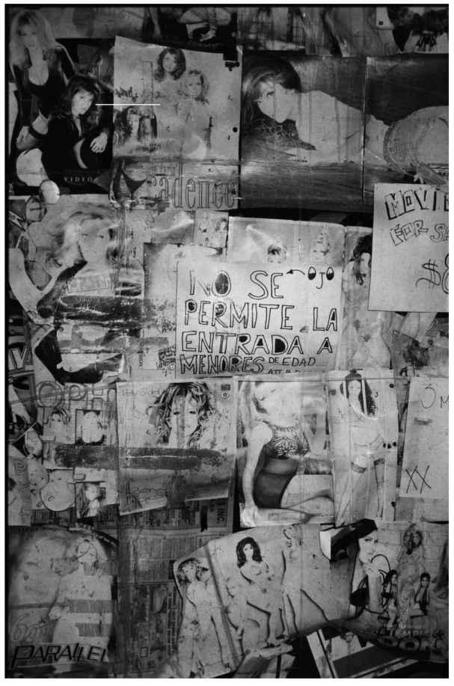

Most of the people I get are like truck drivers who gotta stay overnight in Calexico and they wanna go to a strip bar and get a girl and like that. Part of my job is to see those waitresses don’t rip ’em off. I take pride in my job, man. I care. Sometimes they want me to drink with ’em but I say, no, no, just one beer, two beers or a soda, so I can watch out for ’em. Sometimes it makes me feel lousy, like

wanting;

I wish I had the money for a girl. But on the occasions when they offer to buy me a girl, I always say: Thank you very much, but I got expenses; I’d rather have the money.

The girls, some of ’em are nice; some of ’em have stuck-up ways. Some tell me: Jack up the price so I can give you something. With the price as it is, I can’t give you anything.—But I say: Don’t worry about it. I’m already getting paid.

If I have only a little bit of money I’ll probably wait until two or three in the afternoon to eat lunch, because sometimes I can’t afford to eat three meals. At eight I might have something for my dinner, a little piece of bread, some milk, whatever.

Where to sleep depends on the situation. When a building’s abandoned, you can tell right away, here in Mexico. All of us homeless, we know ’em all by sight. You gotta do what you gotta do. Scariest thing was waking up and this guy was dead. He had OD’d.

103

I called the ambulance, and the police took me in for investigation for forty-eight hours. When we found the guy, I was the last one to leave that building, man. The others were rushing out. I just thought it wasn’t right.

Sometimes, you know, I get bored, especially if I’m getting turned down, so I might start a conversation with some guys or one of the girls. There are disappointments every day. Lupe is luckier than me, just by the simple fact that he can be on

that side.

(And José pointed across the border wall.)

Why don’t you work in a

maquiladora

? I asked him.

Oh, wages are miserable.

104

I know who to go to, he said then, and I understood that he was referring to a border guide.—You know, you get to knowing stories and meeting people. You try to find out who’s the best. The one I have in mind, I see him three or four days out of the week.

How often do you go to jail?

I would say, once a month at least. It’s twenty-four or thirty-six hours. It’s just when they’re making raids and I’m not having permanent ID when I’m here. Now it’s changed. Say, you might even find your money when you get out!

La mordida

105

not to get arrested, is maybe twenty dollars. I’ve done it a few times. Then they won’t mess with you all day.

In prison, show respect but don’t be a coward. If you fight, win it or lose it, you’re all right, because you stood up for yourself.

How often do you go with a girl?

Once a month. Sometimes it’s that girl María. Sometimes I get lucky and find another. If I have a lot of money I might do it every two weeks, maybe in the Nuevo Pacífico. Usually I tell the girls, you know what, you’d better take good care of me. I say the same for my customers, and they give them, not the royal treatment, but it’s okay.

How often do you keep in touch with your family?

I try to phone or wire them every week or every two weeks. I gotta call this little pharmacy store right in town. I send a messenger to go call ’em, since they don’t have a phone or nothing.

Who misses you the most?

I would say none of ’em.

That was the personal information of my friend José López, for which I paid him ten dollars. Why was it that that one thing made me the saddest?

Who misses you the most? I would say none of ’em.

That made me sad, all right. The fact that he had to pay the police just to be left alone to beg all day, that was rough. The fear he suffered when he slept in those abandoned buildings, that I read more in his face than in his words, but it made me pity him. Still, the worst of all was this:

Lupe is luckier.

And at once I could hear Lupe with his head between his hands, groaning:

God, so that’s my life.

Chapter 59

IMPERIAL REPRISE (1905-2003)

1

WATER IS HERE

.

Some people don’t even wanna give you water, man. Some people are just mean.

I can’t help believing in people . . .

2

Yes, just such a man you will see, a hundred times every day in Imperial Valley—the laborer.

I think we all feel sorry for ’em. You know, maybe when I was a kid maybe there were a few leftovers, people who lived in very dilapidated homes, very poor, where there was still white labor.

Trade is leading Culture, a beautiful young woman.

She named the child Imperial Hazel Deed.

White, female, single, daughter, able to read, able to write.

It’s just another die-off. It’s natural.

3

Yes, just such a man you will see, a hundred times every day in Imperial Valley—the laborer.

They contribute little to the economy of the Valley, even though the farmers hype that they do.

But sometimes there’s that black ice and you wait till noon. I’ve worked places where they shine lights on the field so we can keep working at night.

God, so that’s my life.

4

He sold out at a fancy price.

I think we all feel sorry for ’em. God, so that’s my life.

PART FIVE

ELABORATIONS

Chapter 60

THE LINE ITSELF (1895-1926)

Every now and then a word

crosses the border,

. . . marrying another . . .

little by little words turn mestiza . . .

The dark-hued family of words

produces a blond daughter . . .

—Antonio Deltoro, 1999

I

n 1895, San Diego dispatches an alert to lonely Mr. Wadham, the Customs Collector at Tia Juana, California:

I have reason to believe that Mexicans or others who are carrying wood across the line into this country, are engaged in smuggling Cigars and Opium . . .

But what can Mr. Wadham do about it? The line remains little more than an idea.

In 1907, one year after Northside begins to require competency in English as a precondition of naturalization and two years before the first Immigration officials arrive at Calexico, the Asiatic Exclusion League sounds its own call:

Of 2,182 Japs arriving at Mazatlan, advices from mexico informed us that they had nearly all made a bee-line for the border . . .

How terrible! Fortunately, I read in the newspaper ninety-nine years later that the President will take care of everything.

“It makes sense to use fencing along the border in key locations in order to do our job,” Mr. Bush said in a speech at the headquarters of the Yuma Sector Border Patrol. “We’re in the process of making our border the most technologically advanced border in the world.”

Alas, we remain near the beginning of that novel! In 1914, the year after a bridge finally spans the Colorado at Yuma, our Collector at Calexico seizes six cans (three pounds) of smoking opium, but it is only the opium that he gets:

I halted two mexicans on 2nd Street, three blocks east of the Custom House at 6 P.M. Jan. 3rd. One was carrying a sack which I demanded they allow me to search and when I took hold of it, he released his hold and ran for the boundary line which was a block distant. I was unable to overtake or halt him and the other made his escape in the opposite direction.

Such failures to enforce Northside’s authority must have been the rule

. . . Said W. M. Tiller crossed over from Mexico at 11 A.M. April 9, 1914, when hailed by me he started to run. I ran after him and when I had nearly overtaken him he threw himself into an irrigation ditch at the same time throwing the opium into the water.

On the other hand, delineation’s tenuousness facilitated that selfsame authority’s incursions into Southside. In 1906, Colonel William Greene, proprietor of the Sonoran company town of Cananea, suffers inconvenience when his copper miners, whose wages he will not raise to match those of their American coworkers, go on strike. Both sides rack up fatalities. What to do? Colonel Greene calls Governor Izabal, who obligingly accedes to a visit from two hundred and seventy-five Arizona Rangers. There being a line of sorts between Arizona and Mexico, Rangers cross it in dribs and drabs, quite unofficially. Then they commence the job of killing and being killed by Mexicans. Reinforced by the

rurales,

they break the strike.

Returning to territory more directly relevant to this book, I report that in 1915

the Collector cites our amicable relations here, that we have been allowed to pass into Mexico with motor car along our levee track without inspection, or even bothering to give notice . . . as near as I could gather from his Spanish without interrogating him about the matter particularly, he cited the fact that our Imperial

[Canal?]

was allowed to get partly over the line without comment or trouble, and that our shore pipe line is partly in Mexico.