In Amazonia (27 page)

Authors: Hugh Raffles

The day Paul arrived, Umberto Fischer, the owner of FAMASA, had his sawmill manager take him out for the first time to the Projeto de Manejo, the Fazendinha Management Project (FMP). They followed the unpaved road as it veered west across the flattened landscapes. They crossed ranches, stopping to swing open and close the heavy wooden gates, throwing up blankets of red dust as they hurtled past the men repairing miles of wire fencing on these blindingly hot days. Then, one more gate, and they left the glare of pasture behind. Pitching along the dried and rutted mud tracks, suddenly hemmed in all around by the humid crush of broad-leaved trees, palms, and the fragrance of vines.

The FMP was FAMASA's IBAMA-mandated set-aside, a 4,400-hectare rectangle, a forest island in a sea of pasture. In mid-1995, when Paul showed up, IBAMA and FAMASA had already bulldozed a grid of roads that divided the Project into 12 metric tracts or

talhões

, each a more or less 1-kilometer slice off the top of the area's 3-kilometer width. These units had been subdivided in turn by narrow trails hand-cut at 200-meter intervals, every 350-hectare talhão therefore being divided into 16 equal 22-hectare sections.

22

Inside the 12 talhões, IBAMA had instructed FAMASA to nail aluminum tags to selected mahogany “seed trees” (

matrizes

), and the logging team was directed to spare a selection when it came through the area in subsequent years.

Gridded and mapped since 1992, the Project was, in Paul's phrase, “a template awaiting application.” But it was also what he would often describe as a “beat-up” forest, and one indelibly marked by the historical specificities of location. Of the 815 mahogany trees in talhões 1 through 6 recorded by the FAMASA team during demarcation, 640 had

been logged by the time Paul arrived. These, of course, included nearly all the large individuals.

23

Guided by IBAMA, FAMASA had made a significant investment here. As well as the initial disciplining of the site, they set up a small number of 0.5-hectare experimental plots in which they removed all of the understory, creating an airy park-like ambience. They maintained a permanent crew of four men on hand to keep the trails clean and prevent human invasion, and the general sense was that management goals were being met through the simple preservation of the 175 surviving mahogany seed trees.

An interesting narrative of contingency was about to unfold. Although we might expect Umberto, the owner of FAMASA, to feel content with this arrangementâlow investment, minimal overheads, relatively high returnsâhis treatment of the North American visitor was exceptional. Along with his manager and resident agronomist, Umberto gave Paul a tour of the sawmill and associated nursery, and then, as we know, he sent him out over the rough dirt tracks that led to the Project.

That this convergence was based on more than formal politeness would quickly become clear. A room in Umberto's ranch house was soon serving as Paul's base off-site, and Umberto himself became the active sponsor of the Project's redesign. For the first five months of operation, it was his logistical support that enabled Paul to assemble a small team of workers and start building a functional camp. On a weekly basis, Umberto trucked in quantities of food and water (for consumption, and also to maintain a seedling nursery), and he went to the not inconsiderable trouble and expense of having the roads out to the camp graveled so they would be passable through the rainy season.

Of course, there were compensations. Within a short time, the FMP had become an established research site, backed by some prestigious U.S. institutions and worked by a range of North American and Brazilian biologists. And, not long after, the BBC dropped in to film a segment in which the sawmill operator represented responsible mahogany management in the midst of regional disaster.

Yet, given the widespread ambivalence of the Amazonian timber industry toward the ecological imaginaries of foreign researchers, the level of Umberto's commitment requires further explanation. With commercial stocks of madeira de lei virtually extinguished in the south of Pará, the strategies available to the calculating logger are limited. One obvious response is to move out to new areas of extractionâa standard

solution to shortage that is currently sending cutting crews and small-scale sawmills west toward Acre. Anotherâa familiar trajectory once export markets have been secured, although one with a checkered history in the regionâis to experiment with the transfer of valuable species to plantation culture.

24

With additional land deep in the southwest of Pará, and a 350-hectare plantation and nursery adjacent to the Fazendinha sawmill, Umberto was already covering his angles.

Paul's alliance with Umberto emerged from some hard thinking. As one of a group of mostly Brazilian conservation-oriented ecologists working out of IMAZON, a Belém-based non-governmental organization (NGO), his practice was based on dialogue with the very actors who had traditionally been cast as the demonic figures in the Amazonian passion play. As with others in the group, Paul framed his research as an appeal to the instrumentalism of the regional logging industry.

25

Although such Faustian politics are troubling to environmental absolutists, in this respect, at least, the IMAZON team was working within a well-established lineage. As Yrjö Haila has pointed out, ecology has long been a worldly science. Indeed, “nearly every ecologist active at the turn of the [twentieth] century was involved in solving practical problems in such diverse fields as agriculture, forestry, fisheries, demography and life insurance statistics.”

26

Despite his own emotional investments, Paul publicly distanced himself from activists campaigning for a logging moratorium, and he took a tactically agnostic position on the acrimonious disputes between extraction and conservation advocates over the listing of mahogany under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

27

Despite his personal commitments, his public self-fashioningâexpressed in proposals, field reports, and presentationsâwas as the modest technocrat, disinterestedly producing the facts necessary for an apolitical adjudication.

28

It was the loggers, Paul argued, who had most to gain from the life-history data on phenology, pollination, seed dispersal, and seedling response to manipulation that he was collecting. Despite the radical short-termism of their practice, they were, he pointed out, the only significant regional actors with both a stake in protecting long-term forest cover and the capacity to do so.

29

Twenty years after the ferocious clearances of south Paráâin which mahogany stems as slender as 30 centimeter diameter breast height (dbh) or less were takenâthere was still no possibility of a profitable second cut. Moreover, the standard trajectory was to wholesale conversion to pasture, burning the now sought-after

madeira

branca

, the second-quality timber, along with material of no commercial value.

30

Conveniently located high-value timber no longer existed in quantity, and the lower-grade woods were being brought in from considerable distances.

It was, then, a favorable conjuncture for strategic alliance. By providing the basic data that would enable some fairly simple changes to the timing and intensity of harvestingâsynchronizing extraction with seed production and seedling growth, for exampleâPaul offered Umberto the prospect of shifting mahogany logging onto a cyclical regime structured around elements of longer-term, albeit lower-intensity, productivity. In the context of international pressure for a ban on mahogany logging, this was a proposition worth entertainingâat least until it impinged on normal business practice.

Despite the palpable sense of gathering crisis, both ecologist and logger knew that the exhaustion of bigleaf mahogany remained spatially restricted. Although they were fairly safe in predicting the tree eventually becoming so rare at valuable sizes as to be commercially extinct outside plantations, not only was that not yet the case, but improved transport infrastructure and enhanced industry mobility meant that loggers' fields of activity were fully expandable across this adaptable species' entire range.

31

Moreover, as Paul and his colleagues knew, their appeal to an economic rationality mediated by an ethic of sustainability and a notion of evenly unfolding time was of limited force in a world of prolonged primitive accumulation, quite particular cultural and political-economic logics, and perpetual crisis. For one thing, as we have seen, while struggles over land ownership, occupation, and life itself remained so volatile and fluid in Amazonia, neither ranchers, loggers, nor poor colonists were much inclined to think in terms of forest-based futures.

There is, though, little naïveté here. Compared to an earlier age of applied ecological research in the Amazon (when experts blithely encouraged farmers to adopt impossibly high-input agricultural practices as a means of stabilizing “frontier expansion”),

32

contemporary natural scientists and their interlocutors operate in a world of decided realpolitik, forging collaborations where they may. Much of this pragmatism is enforced by the politics of negotiating multiple publics. For Paul and Umberto, mahogany is possessed of a transformative translocality. This is a tree that travels, a tree that creates anew those with whom it comes into contact, and that does so through itsâand thus theirâ

interpellation in a set of debates that can be lively to the point of violence. Thanks to mahogany, it is around the FMP that diverse and overlapping sets of human actors get drawn together: officials of IBAMA and the U.S. Forest Service, NGO activists, timber industry advocates, journalists, academic researchers, and multiply positioned residents of south Pará. Their exchanges are shot through with the crisis-driven rhetorics of biodiversity and habitat conservation, the combative confidence of the neoliberal assertion of entrepreneurial rights, and the authoritative expansion of natural scientific expertise into the realm of social policy.

33

Mahogany is a species of many parts, and one of Paul's tasks is to ensure that the fetishized aura of its wood is displaced by the (differently fetishized) integrity of its tree-ness. Out of a particularly crushing and disabling anonymityâthe absence even of a convincing life historyâthe FMP aims to produce a cosmopolitan tree with a localized meaning and specificity, a richly situated yet mobile identity. Deep in the interstices of instrumentalism, holding it all together in fact, it turns out that this Project is an affective work of creation: for Paul, a collaboration built on affinities both human and non-human; for Umberto, a moment of curiosity, and, perhaps, in a haphazard way, of redemption.

These, though, are alliances born and raised in contingency. By the time I arrived in Redenção in July 1999, Umberto's stormy relationship with his ex-wife had degenerated into wrangling over filial inheritance. The FMP became just one of several parcels seized on by impatient daughters, andâover Umberto's ineffectual objectionsâimmediately sold to Coutinho, a much larger regional lumber concern. Paul, unceremoniously, had been given one more year to wrap up and leave. Unless, that is, he could come up with U.S. $1.7 million and exercise his option to purchase the Project.

W

OOD OF

W

OODS

Mahogany is no longer what it was in the early 1900s, when Allan Carman, “biographer to His Majesty,” wrote the

Monarch of Mahogany Visits Schmieg-Hungate & Kotzian

.

34

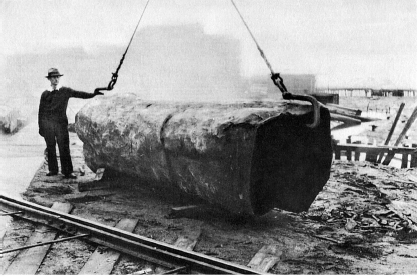

Schmieg-Hungate & Kotzian were an Upper East Side Manhattan furniture-maker, and this royal tour begins with a grainy photo of the Monarch's arrival in New York: a very large log lowered on a very muddy dockside, heavy metal hooks

in each end, an anonymous man in hat and black gloves looking impassively on.

The arrival of the Monarch of Mahogany at New York

What now seems a rather desultory image takes us to a time and place in which the extraordinary reach and persuasiveness of capital was a cause for confidence rather than anxiety. The Monarch, Carman writes, is now over 300 years old. He was raised in the forests of Cuba, and has been located with only the greatest difficulty. He must be “induced” to leave his homeland. He must be informed that “suitable arrangements [will] be made for his comfort,” that the most up-to-date facilities have been prepared, that the finest craftsmen await him, and, rather ominously, that “a most interesting program of usefulness [has been] outlined.”

35

For Carman, Schmieg-Hungate, and their Manhattan clients, the Monarch's life is just beginning. All that went beforeâthose stately centuriesâwas mere preparation. In a truly modern inversion of the environmental narratives with which we are now so familiar, fulfillment and self-realization lie in the bourgeois transformations of the commodity form: a reproduction Chippendale armchair, a tripod table, and a “lovely” period commode, each purchase verified by a certificate

of authenticity and the evidential tactility of that image of arrival on a rainy New York morning.