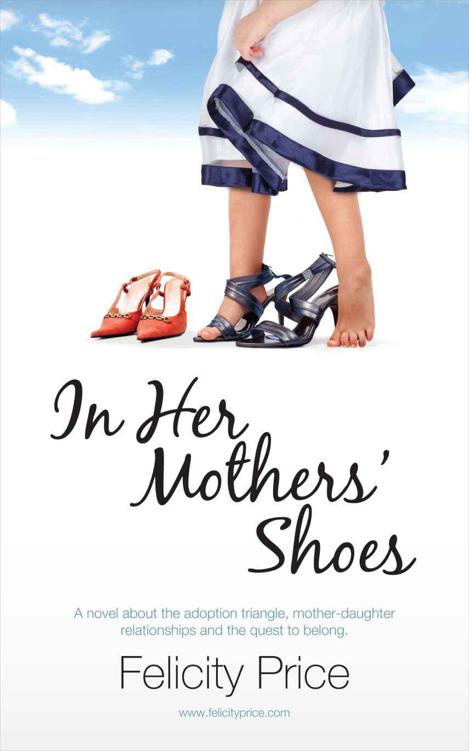

In Her Mothers' Shoes

Read In Her Mothers' Shoes Online

Authors: Felicity Price

In Her Mothers’ Shoes

a novel based on three true stories

by

Felicity Price

www.felicityprice.com

“In Her Mothers’ Shoes” is dedicated to both my mothers.

© Copyright 2012 Felicity Price

“Sometimes when you read a book, you can’t imagine why it has never been written before: it seems so self evidently a story waiting to be told, and in just that fashion. This is that kind of book.” –

Fiona Farrell, Author.

This book is “social history as much as a study in character,” written with “a style that is open, often funny and frequently affecting.” -

Damien Wilkins, Author

~ ~ ~

Other titles by Felicity Price available on Amazon Kindle:

A Sandwich Short of a Picnic, 2010

Head Over Heels, 2011

Part 1: Lizzie

Chapter 1

Wellington. Late June, 1950

The tram rattled slowly up the hill, lights blazing against the driving rain and eerie darkness. Through the window, Lizzie watched as the fractured shadows over pavements and parked cars flattened into the puddles at her school gates. She ducked her head, recognising someone; she didn’t want any questions tomorrow.

The tram was almost empty, the after-work rush over. Up the front, Peter was joking with the driver, who kept ringing the bell and looking back in her direction, grinning like a manic monkey. What was so funny? Was it her?

Peter, tall and proud in his conductor’s uniform, cockily aware of his attraction, smiled and winked. She smiled back, nervous, uncertain.

For a moment she thought of running to the back door and jumping off, joining the flickering shadows at the side of the road. But she stayed in her seat, felt the smooth, varnished wooden slats between her fingers, traced the grooves of carved initials, then turned away and looked out the window again.

What was she doing here?

It was Steven Davidson’s fault; he was the reason she was chasing after this man who collected the fares and clicked the tickets on the Karori line. Peter might look smart in his fitted uniform; he might give her cheek and make jokes that sounded so clever and witty, even though she didn’t really understand them; he might have the dark attraction of the other side of the tracks, with his rough accent and abrupt finish to his schooling at the age of fifteen; but he wasn’t right for her.

Who

was

her type? Was it Steven Davidson, the Wellington College seventh former she’d met at Ruapehu last weekend? Although not as off limits as Peter, her mother wouldn’t approve of him either; he didn’t go to Scots.

She had little chance to meet boys. There were none at her all-girls’ school, and there were none who’d caught her eye on the tram-ride home from trips to town – until that afternoon weeks ago when Peter had held onto her ticket for much longer than necessary then teased her when she tried to take it from him. He’d winked, made one of his unintelligible jokes, and the next time she made the trip had persuaded her to ride the tram all the way to the end of the line at the Karori Pavilion, where they’d talked, laughed a lot and, just as the driver had rung the bell for the tram to turn around and go back to the city, Peter had leant over and kissed her, lightly, on the lips.

She’d expected her first kiss – not counting the one with the boy in the sandpit at primary school – to bring some sense of excitement, of romance, but she’d felt little more than a slight fluttering in the pit of her stomach.

It was nothing compared to the jolt when Steven had fallen on top of her in the ski lodge just over a fortnight ago. She smiled at the recollection. Everyone had been sitting in the chalet’s big common room, the pot-bellied stove burning furiously in the corner, the dinner dishes done and put away. The boys from Wellington College – all six of them – were drinking beer from brown quart bottles. They’d offered Lizzie and her friend Julia a swig.

No thanks, they’d said, a bit giggly over being singled out. But they hadn’t said no to a hot mug of mulled wine that the group of adults had brewed up after they’d all come in from skiing, cold from the biting wind outside. She could feel the warm glow, could smell the aromatic spices and taste the thin slice of orange with its strong alcoholic bite. Her parents never offered her such delights; her parents weren’t there.

She and Julia had caught the ski bus from town, along with a crowd of others their age, to stay at the club lodge without either of their parents for the first time.They’d both felt as if they were living a little on the edge, as if anything were possible.

‘Let’s have the indoor ski race,’ one of the boys from their bus called out.

There was a scrabble for the door and soon four boys returned brandishing a pair of long wooden skis each, clumping awkwardly down the steps in their heavy ski boots. One of them was Steven.

Lizzie and Julia had stayed seated on the bench seat, leaning back on the sturdy wooden table, sipping at their mulled wine, laughing with the others, knowing what was about to happen. Indoor ski races had been a regular nightly occurrence at the lodge over the years after the boys – and some of the girls – had downed a few drinks.

Steven, who’d introduced himself to Lizzie while they were standing next to each other in the rope-tow queue that morning, was lining up with the other three at the far end of the room, a path in front cleared of clothing and bottles.

‘On your marks… Get set …. Go!’

They were off, shuffling their skis with as much speed as they could muster, jockeying for position who could get up the stairs first, pulling themselves up by the handrails, poles flailing, and suddenly they were gone, outside into the snow, where Lizzie knew they’d be poling themselves once around the lodge. Inside, everyone was cheering, catching glimpses of the racers as they flashed past each window, until they burst back in the door, fighting to be first down the stairs and into the middle of the room.

Steven flung himself at the finish line, crossing just ahead of the next boy then toppled in a heap at Lizzie’s feet, grazing her knee with his pole.

‘Sorry, Lizzie.’ He was bright red with the effort, sweat had broken out on his forehead, and he was grinning happily. He’d remembered her name! And as he brushed against her, she’d felt a huge thrill, almost as if he’d hit her in the stomach.

‘You won, Steven! Well done.’ Lizzie jumped up and started to help him up off the floor.

‘I’ll be all right. I just need to get these skis off.’

Lizzie helped release his bindings and their fingers met as he reached for the lever at the same time. Again, that thrill. She looked at him. By the expression on his face, there was no doubt he’d felt it too.

They’d spent ages talking around the table, with Julia and the other boys, then on their own. Later, as they’d walked to their separate bunkrooms, he’d held her hand, pulled her awkwardly towards him and held her close for a moment. Then he’d said good night and disappeared inside the men’s bunkroom door.

He hadn’t kissed her. What was wrong with her that he hadn’t kissed her? It was Saturday night – they had to get the bus home on Sunday, there would be no other opportunity. Maybe he didn’t like her after all? Maybe she’d just imagined it. All the way home, she wondered, she dissected that moment in the bus with Julia: where had she gone wrong?

‘Karori terminus. End of the line.’ Peter was making his way down the aisle towards her. All the other passengers had gone.

‘You coming, love?’ That cheeky grin, that sparkle in his eye, daring her to follow.

Why not, she thought. Steven hadn’t tried to make any contact with her since that weekend at Ruapehu. He knew her name, what school she went to. It wouldn’t have been hard to find her, to give her a call. At first, she’d jumped to answer the phone every time in rang in the hall. But after two weeks, she’d given up. He wasn’t going to call. He didn’t care.

Peter cared. Peter carried an air of danger, of risk, and she liked that. She could tell by the way he talked he was from a rougher part of town, the other side of the tracks her mother would say, and that had its own appeal. He was very good looking, he was three years older than her – not a silly schoolboy who didn’t know how to kiss – and there was something about him, about his uniform, his smile, his impudence, that was unaccountably attractive.

He pulled her towards him and planted his mouth on top of hers, kissing her roughly. She could taste tobacco and smell something raw and wild about him that made her respond just as roughly. In the pit of her stomach, something stirred, shooting right through her, burning, breathtaking. He knew how to kiss.

‘Come on then.’ He broke away from her and strode towards the pavilion without looking back.

She splashed across the road and the shingle carpark, trying to keep up. This time, instead of heading round the back, he veered to the left and stopped outside the men’s toilets. She stopped, unable to move forward. This didn’t seem right. The stench of ammonia was so powerful that Lizzie thought she would gag.

She knew it wasn’t sensible, she knew her father wouldn’t approve, but still she followed.

How often had she accompanied her father at weekends to watch cricket at the Karori Pavilion? She’d lost count. But that was in daylight, under the summer sun. This was midwinter, well after dark and so cold her bare legs were blotched blue and white. The Karori Pavilion was familiar. But the Men’s toilets weren’t.

Perhaps she should turn back. She was beginning to feel less daring with every second that passed. She hesitated, clutching the iron railing, wondering if she should make a run for it.

Peter turned the handle and pushed open the heavy wrought-iron gate.

‘It’s okay, love, there’s nobody here,’ he called.

She emerged from the shadow of the dripping bushes and walked cautiously up the ramp to stand beside him, half blinded by the vicious light shining in her eyes from above the Men’s door. How had it come to this?