In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES (33 page)

Read In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES Online

Authors: Arika Okrent

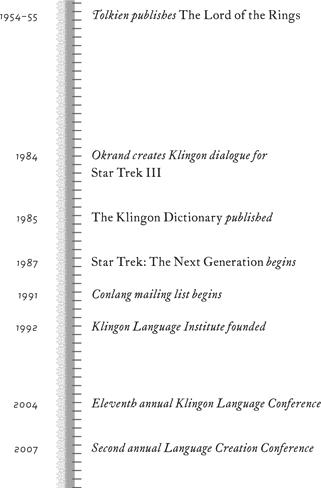

After ten years passed, and women had still not embraced Láadan or come up with another language to replace it, Elgin declared the experiment a failure, noting, with some bitterness, that

Klingon (a hyper-male “warrior” language) was thriving. Still, she had found the challenge interesting and “well worth the effort.”

Bob LeChevalier, who discovered Láadan through his contacts in the science fiction community, found certain aspects of the language so interesting that he was inspired to adapt them for Lojban. After checking with Elgin to make sure she didn't mind (she didn't), the Lojbanists developed their own system of evidential markers, as well as a set of special indicators that greatly expanded the range of speaker emotions, attitudes, and intentions that could be expressed. Of course, they ran with it in the usual Lojban way and ended up with a system capable of distinguishing among hundreds, maybe thousands of feelings. Along with

ui

([happiness] Yay!),

u'u

([repentance] I feel guilty),

it

([fear] Eek!), and

.o'u

([relaxation] Phew!), there are compound indicators ranging from

.uecu'i

([surprise][neutral] ho hum), to

.o'unairo'a

([relaxation][opposite][social] I feel social discomfort), to

.uiro'obe'unai

([happiness][physical][lack/need][opposite] Yay![physical] Enough!), something you might say after enjoying a big meal. As the Lojban grammar states, “We have tried to err on the side of overkill. There are distinctions possible in this system that no one may care to make in any culture.”

Strictly speaking, these indicators fall outside the realm of formal logic: their validity cannot be evaluated; there are no truth tables that can account for them. But the Lojbanists love them, and they have a lot of fun playing with them. So much fun that one of them proposed a new language called Cinban (from

cinmo bangu

, “emotion language”), which would just be English with the attitudinal indicators thrown in, something the Lojbanists had been doing casually for a long time. He set up a new Web forum in which “to practice .o'o [patience] using Cinban until I'm fully fluent

.a'o

[hopefully] in it. Anyone's welcome

.e'uro'a

[suggestion, social] to join me, of course

uenaidai

[expectation, empathy].” Using the indicators often, and in a creative way, is a hallmark of Lojbanness—which is to say, something Lojban culture values highly.

Lojban culture? A language, of course, once it gets off the drawing board and into the hands of people who use it, can never be culture-free. Loglan, and Lojban after it, were bound to develop a culture of their own. They attracted a self-selecting group of people who already shared many of the same interests and thought about things in similar ways. As one of them put it in an early issue of the

Loglanist

, Loglan speakers “have a prior weird-ness that ruins any whorf-test.” To become a Loglanist, you had to, in a certain sense, already think like a Loglanist. James Cooke Brown did not see this as too much of a problem, though, because the experimental tests that were expected to eventually occur would be performed not on the Loglanists who had developed the language but on “normal” subjects, who would learn Loglan in the (culturally) sterile environment of the laboratory. Some Lojbanists still dream of the day when the laboratory tests will finally be implemented, but it is unclear whether even they themselves are capable of learning Lojban to a level of basic proficiency, much less any “normal” people.

Though Brown put an enormous amount of detailed engineering into his experimental tool, he never had more than a vague and unrealistic plan for how any actual experiments would be conducted. The experiments never took place, and it looks like they never will. While Brown and his followers toiled away on Loglan, the Whorfian hypothesis endured a long half century of being proven, disproven, defended, demolished, revived, mocked, and revived again. Over time, researchers brave enough to get near the Whorfian question have devised increasingly refined experiments

designed to look for very specific effects under strict conditions of control. In this context, the idea that you could do something as broad as teach someone an entire made-up language (so many confounding factors!) and look for some kind of effect on thought (measured how?) looks downright amateur.

But the experiments are beside the point now. The Lojbanists are living out their own personal Whorfian tests. They report that learning Lojban makes them more clear in their use of English; it makes them better at drawing correct logical inferences; it makes them more aware of their metaphysical assumptions, causing them to reexamine their views of the world. They find it mind opening, and these results, anecdotal and unscientific as they may be, are satisfying in their own way. As one Logfest participant told me, “I like how it messes with my head.”

Somewhat accidentally, the Lojbanists have come to follow Whorf's own intended program more closely than did any of the researchers who interpreted his work as a hypothesis that needed to be tested. Whorf took his linguistic relativity principle as a given: different types of grammars “point” people toward different views of the world. The job for the researcher was not to see

whether

this was true but to explore

how

it was true. If we were to do this right, we had to be made conscious of our own hidden, language-conditioned thought habits. And the best way to become conscious of them was “through an exotic language, for in its study we are at long last pushed willy-nilly out of our own ruts. Then we find that the exotic language is a mirror held up to our own.”

Loglan did not become the sober, scientific instrument it was intended to be. It will never prove or disprove anything about the Whorfian hypothesis. However, as it evolved into the Lojban of today by committing itself to its contradictory goals of becoming

a language of everything, nothing, and something, it transformed into a different kind of instrument—an enormous, minutely faceted fun-house mirror that, if it doesn't freak you out too much, will definitely push you out of some of those ruts Whorf was talking about. It's not science, but it just might be art.

Flaws or

Flaws orFeatures?

T

he story of invented languages has not been entirely a story of failure. While Wilkins's project did not become a universal language of truth, he produced an extraordinary document, a snapshot of linguistic meaning in his culture and era—and paved the way for the thesaurus. Esperanto did not become an auxiliary language for the whole world, but it did become a real, living language, and in the small sphere of people who use it, it does seem to promote a general atmosphere of international understanding and respect. Blissymbolics found a way to be useful, despite the wishes and actions of its creator, and Loglan lives on today, despite not having fulfilled its scientific mission.

One could argue that the “success” of these languages is only accidental, and makes their inventors no less naive, or

misguided, or presumptuous. Just because they produced something that turned out to have some value for someone doesn't mean they deserve to be admired. We

should

admire them, however, for their raw diligence, not because hard work is a virtue in itself, but because they took their ideas about language as far as they could go and really put them to the test. Who hasn't at one time or another casually suggested that we would be better off if words had more exact meanings, or if people paid more attention to logic when they talked? How many have unthinkingly swooned at the “magic” of Chinese symbols or blamed acrimony between nations on language differences? We don't take responsibility for these fleeting assumptions, and consequently we don't suffer for them. The language inventors do, and consequently they did. If we pay attention to the successes and failures of the language inventors, we can learn their hard-earned lessons for free.

We can also gain a deeper appreciation for natural language and the messy qualities that give it so much flexibility and power, and that make it so much more than a simple communication device. The ambiguity and lack of precision allow it to serve as an instrument of thought

formulation

, of experimentation and discovery. We don't have to know exactly what we mean before we speak; we can figure it out as we go along. Or not. We can talk just to talk, to be social, to feel connected, to participate. At the same time natural language still works as an instrument of thought transmission, one that can be

made

extremely precise and reliable when we need it to be, or left loose and sloppy when we can't spare the time or effort.

When it is important that misunderstandings be avoided, we have access to the same mechanism that allowed Shirley McNaughton's students to make use of the vague and imprecise Blissymbols, or that allows deaf people to improvise an international

sign language—negotiation. We can ask questions, check for signs of confusion, repeat ourselves in multiple ways. More important, we have access to something that language inventors have typically disregarded or even disdained—“mere” conventional agreement, a shared culture in which definitions have been established by habit. It is convention that allows us to approach a Loglan level of precision in academic and scientific papers or legal documents. Of course to benefit from the precision, you must be “in on” the conventional agreements on which those modes of communication depend. That's why when specialists want to communicate with a general or lay audience—those who don't know the conventions—they have to move back toward the techniques of negotiation: slowing down, answering questions, explaining terms, illustrating with examples. Convention is a faster, more efficient instrument of meaning transmission, but it comes with a cost. You have to learn the conventions. In the extreme cases this means a few years of graduate training or law school. In general it means getting experience with the way other speakers—of English, Spanish, Greenlandic Eskimo, or whatever language you're interested in learning—use their words and phrases.

When language inventors try to bypass convention—to make a language that is “self-explanatory” or “universal”—they either make a less efficient communication tool, one that shifts too much of the burden to negotiation, like Blissymbolics, or take away too much flexibility by over-determining meaning, like Wilkins's system did. When they try to take away culture, the place where linguistic conventions are made, they have to substitute something else—like the six-hundred-page book of rules that define Lojban, and that, to date, no human has been able to learn well enough to comfortably engage in the type of conversation that any second-semester language class should be able to handle.

There are types of communication, such as the “language” of music, that may allow us to access some kind of universal meaning or emotion, but give us no way to say, “I left my purse in the car.” There are unambiguous systems, such as computer programming languages, that allow us to instruct a machine to perform a certain task, but we must be so explicit about meanings we can normally trust to inference or common sense that it can take hours or days of programming work to achieve even the simplest results. Natural languages may be less universal than music and less precise than programming languages, but they are far more versatile, and useful in our everyday lives, than either.