In the Shadow of Blackbirds (20 page)

Read In the Shadow of Blackbirds Online

Authors: Cat Winters

Desperate,

I wrote on my paper.

They’re always desperate.

I read about ectoplasm that was proved to be cheesecloth, unexplained spirit voices, spirit lovers, spirit writings, spirit photographs, spirit manifestations, and even two girls in Cottingley, England, who claimed to be photographing fairies. My brain raced, and my sheets of paper filled with notes and diagrams and formulas and poetry.

But I still had no idea why Stephen thought monstrous birds were tying him down and killing him.

“DO YOU KNOW HOW I CAN GET TO THE NEW RED CROSS

House in Balboa Park?” I asked the same brunette librarian who had helped me before.

She slid my stack of five checked-out books across the polished countertop. “Take the Fifth Avenue streetcar up to Laurel. You’ll find a bridge crossing the canyon to Balboa Park.”

“Is the park small? Will it be hard to find?”

She raised her eyebrows. “You’ve never been there?”

I shook my head.

She laughed. “Well, I guarantee you won’t miss it when you get to the bridge. It’s the former site of the Panama-California Exposition. The military owns the area now, but somebody could probably direct you to the Red Cross House. Do you know someone recuperating there?”

“No, but I’d like to volunteer.”

She leaned her gauze-swathed chin against her fist and studied me. “How old are you?”

“Sixteen.”

“Does anyone know you’re wandering around in the quarantined city by yourself?”

“I said I’m sixteen, not six.”

“That doesn’t answer my question.”

Instead of responding, I opened the wide mouth of my mother’s black bag and crammed it full of books.

The librarian ducked below the counter. “Here.” She stood up straight again and slid a red pack of garlic-flavored gum across to me. “Take a stick or two. I can’t stand the thought of sending a kid across town without some flu protection.”

“You sound like my aunt. If she had her way, I’d be bathing in onion soup every night.”

“Just take it, please. Take the whole pack. I can buy another.” She folded her slender hands on the counter. “It would be a shame to waste all that curiosity to the flu.”

I took the pack, and to make her feel better, I even slipped my mask down for a moment and popped one of the foul sticks of gum in my mouth. Instant tears careened down my cheeks. “Ugh.” I spit the gum out in my hand. “This is awful.”

“Just chew it, OK? Stay safe out there.” She nodded toward the exit. “Now go on. I’m getting tired of crying over kids who don’t have anyone to watch over them anymore.” She turned away from me and stooped down to a collection of books on a low shelf behind her.

I hesitated, soothed by the taste of concern trailing off her, almost tempted to stay. She looked back to see if I had gone, her eyes shining with tears, so I thanked her and slipped away.

I GAGGED ON THE TASTE OF THE GARLIC GUM WHILE A

bright yellow streetcar carried me along the rails to the hills above San Diego. Three businessmen in smart felt hats rode with me, probably on their lunch break. They buried their gauze-covered noses in the

San Diego Union,

and one of them read the October influenza death tolls out loud.

“Philadelphia: over eleven thousand dead and counting—just this month. Holy Moses! Boston: four thousand dead.”

The use of cold statistics to describe the loss of precious lives made me ill. I crossed my fingers and hoped that Portland wasn’t a big enough city to mention. Hearing the death toll up there—worrying about my father in that crowded jail—would have probably killed me.

“New York City: eight hundred and fifty-one in just one day—

eight hundred and fifty-one!

Can you believe that?”

“Laurel Street,” called the conductor from his post by the center doors.

I pressed a fancy little nickel-plate button inlaid in mother-of-pearl, relieved for the chance to escape. The car came to a gentle stop on a flat part of the street.

“Where’s the bridge to Balboa Park?” I asked the conductor before heading down the steps.

“Straight to the east.” He pointed with a long arm, and like the librarian, he added, “You can’t miss it.”

He was right. A nearsighted person without glasses could have spotted it from more than a block away: an elaborate arched concrete bridge spanned a pond and a canyon, and on the other side of the hundred-foot drop rose a city of Spanish colonial palaces, straight from the pages of a fairy tale.

I walked briskly across the bridge, eager to reach the Red Cross House and urged on by a feeling in my gut that someone there would be able to help me with Stephen. I ran below curved balconies, wrought-iron railings, and plaster pillars sculpted with intricate flowers, grapes, and rambling vines. It would have been amazing to simply stand there and gape at the architecture, but not when I had a mission.

The building I sought stood out like a beacon, for a large red cross marked its roof. I slowed my pace as I approached the daunting entrance, my heart thumping as if I were about to come face-to-face with Stephen himself.

Inside, the main room must have stretched two hundred feet across, and bandaged, wounded men were everywhere. They read and slept on sofas and padded leather chairs, or hobbled about on crutches. Others were confined to wicker wheelchairs. A few groups who didn’t look as battered as the rest huddled around tables and played cards. Canaries sang from wire cages. Two open fireplaces warmed the air. No one, save those warbling canaries, made much noise.

Along with the garlic fumes heating my tongue, the rancid taste of suffering drenched my mouth, as if someone were pouring week-old soup prepared with spoiled meat and stagnant water down my throat. I yanked off my gauze and threw the wad of gum into a wastebasket.

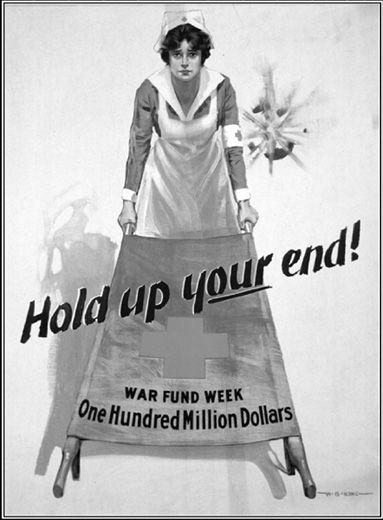

A woman with eyes as amber and narrow as a cat’s came my way in a white Red Cross hat and clip-clopping heels. She straightened her flu mask over a nose that appeared rather large, smoothed out the crisp apron covering her pressed gray uniform, and took a long look at my doctor’s bag.

“I’m not a doctor,” I said. “I’m just carrying some library books in the bag.” I tugged my gauze back over my mouth and nose. “It belonged to my mother.”

“Oh.” She blinked like she didn’t know how to respond to such an introduction.

“My name is Mary Black,” I tried again, omitting the “Shelley” to avoid associations with

Frankenstein

and Germany in an American Red Cross building. “I’d like to volunteer to help the men.”

She surveyed my appearance, from the childish white ribbon tying back my hair at my neck to the worn-out Boy Scout boots that were coming unlaced. “How old are you?”

“Sixteen. And a half.”

“That’s a little young to be witnessing the state of some of these men. Most of our volunteers are married women who’ve seen a bit of life already. They’ve experienced childbirth. They’ve lost husbands.”

“I just buried a boy who meant the world to me, ma’am. I’ve seen corpses as blue as ripe huckleberries lying in front yards out there. There’s no need to protect me from anything.” I shifted my sagging bag to my other hand. “I’m tired of sitting around doing nothing.”

She swallowed. “Very well. Are you up to serving the men refreshments and making sure they’re comfortable? Helping them write letters and whatnot?”

“Yes.”

She stepped closer and softened her voice. “Several of the men are amputees, and some of their faces are quite damaged beneath their bandages. You may see signs of deformed cheeks and chins and missing facial bones. Are you sure you can do this?”

“I’m positive.”

“All right, then. Please avert your eyes if you need to, but try not to express disgust. Our goal is to help them recover in the most soothing environment we can offer.”

“I understand.” I peeked at the quiet gathering of broken

boys beyond us. “Why are so many of their faces disfigured, if you don’t mind me asking? Is it the explosive shells they’re using over there?”

“I’m told it’s the machine guns. Curious soldiers will often lift their heads out of the trenches, thinking they can dodge bullets in time, but there’s no way they can possibly avoid the hail of machine-gun fire.” She glanced over her shoulder. “We tend to also see several missing left arms because of the way they position themselves for shooting in the trenches. Their bones shatter into tiny fragments and their wristwatches become embedded in their wounds. There’s no way to save the limbs.”

I didn’t cringe, for I felt she was testing me, and I was determined to prove I could handle the horrors. “What can I do first?”

Her heels clicked over to a woven tan basket sitting on one of the front tables. “Well, I was just about to pass around these oatmeal cookies. Why don’t you give that a try?” She carried the basket my way. “Heaven knows, these boys would probably love to be offered baked goods by a pretty young girl. Just be careful none of them gets too fresh with you.”

I looped the basket handle over my arm and soaked up the scents of baked oatmeal and roasted nuts—a divine combination that curbed the rancidness inside my mouth.

“Is there a particular part of the room where I should start?” I asked.

“It doesn’t matter. They’re all in need of cheering. If

the men are too much for you to take, come into the back kitchen. We can always have you help bake something or roll bandages.”

“I’ll be fine. Thank you.” I dropped my black bag by the front door, and then I journeyed into the main room, trying to convey confidence in my stride.

Where to start, where to start?

I wondered, unsure if I would be more helpful in one direction versus another. At random, I picked the right.

The first two young men I approached were sitting in fat leather armchairs reading outdated copies of the

Saturday Evening Post.

I remembered the picture of the clown on the rightmost cover from way back in May or June. The black-haired boy reading that particular issue was missing both his legs, his trousers sewn to hide the two stumps. The other young man, a handsome devil with golden-brown hair and smoky-gray eyes, wore bandages over his left wrist where his hand ought to have been. An unlit cigarette dangled from the scarred fingers of his surviving hand.

“Would you like a cookie?” I asked the black-haired one.

He looked to be of Mexican descent, with olive skin and dark irises that brightened when he found me standing over him. “Yes, please,” he said.

I handed him one of the lumpy oatmeal cookies and kept my attention from straying to his two stumps. “Here you are.”

“Thank you.” He untied the top strings of his flu mask and revealed a boyish round face with a healing pink gash across

his chin. “You’re much younger than the ladies who usually help around here,” he said.

“Qué bonita.

Very pretty.”

“Thank you.”

“No, thank you,

querida.”

“Please excuse Carlos,” said the other boy with a cockeyed smirk I could see through a round opening cut in the center of his mask. “They dope him up with morphine so he doesn’t feel the …” He pointed with his cigarette to Carlos’s missing legs. “He’s under the delusion he’s still a Latin lover.”

“I’m twice the man you are, Jones.”

“Said the man with no legs,” chuckled the blondish boy.

“Not funny, friend. You’re just jealous the ladies fuss over you less.” Carlos leaned back in his chair and beamed up at me. “Do us lovesick fellows a favor,

querida.

Take down your flu mask. Let us see your entire beautiful face.”

“You don’t need to see my whole face.”

“But I do,” said Carlos.

“You’ll be sorely disappointed.” I lifted another cookie out of the basket. “I have huge warts and buckteeth hiding under my mask.”

“Don’t tease us.” Carlos gave me a pleading look with his big brown eyes. “We’re starving for female attention,

querida.

Just one quick peek.”

“I’m afraid not.” I offered the cookie I was holding to his friend Jones. “Would you like one of these?”

“No.” The blondish boy slid his cigarette between his lips through his mask hole. “But I’d love a light.” He raised his

narrow hips and yanked a matchbook out of his back pocket with a grimace. His other arm, the one with the missing hand, lay across his left leg as if it were something dead.