Indigo (20 page)

Authors: Clemens J. Setz

â Did he . . . say something nasty . . . ? Like Frau Rabl's son?

Max Schaufler. How . . . ?

Robert wasn't good at crying. It wasn't his way. He knew lots of people who were really good at it, who could really cry you something, a whole story, an étude by Chopin, a social contract, a career leap. But he couldn't do it. Had never learned how. His face always just came apart, like continental drift, and the individual pieces did what they pleased.

â Oh, Robert, don't, that was just a . . . (a pause lasting a tenth of a second, because she didn't know, she had to guess) . . . a stupid, intolerant asshole who said something . . . No, don't cry, come . . .

5.

The Quincunx

On the soccer field the grass grew knee-high, it hadn't been mowed for quite some time. I asked the principal about it, and he only shrugged and said that in summer, in any case, games would be played here again. On the large meadow next to the playing field stood several trees that had just begun to bloom. A slight figure moved among them with strangely jagged and irregular steps. The principal stopped and told me to do the same. He shielded his eyes with both hands, then whistled by sticking two fingers in his mouth. The figure, a boy who was carrying something around with him that looked like an empty birdcage, responded with a similar whistle. In the principal's face was a certain strain, but also a genuine excitement, as if he were looking forward to the imminent encounter.

â Max! he shouted, beckoning the boy toward us.

â Is he . . . ?

The principal turned to me and nodded.

â Yes, he's from here. A really sweet boy. One we've pinned our hopes on! His parents are incredibly nice too. His father recently purchased a paper mill from . . . Yes, Max, hello!

â Good morning! shouted the boy, remaining at about ten yards' distance.

The principal approached him, the boy first backed away a little, then understood and extended his hand so that the principal could shake it.

â Come on over, he said, waving me closer. He doesn't bite, haha!

The boy named Max held out his hand to me, and when I took it, I noticed that it was ice-cold. Probably he was nervous.

â We'll stay a few minutes, the principal said with a kind smile in my direction. So, yes, Max, this is Herr Seitz, he is going to . . .

He made a gesture that was apparently supposed to signal that I should finish the sentence.

â I'm doing my teaching internship here.

The boy nodded. He put the empty birdcage down in the grass.

â Yes, the principal said enthusiastically. He will serve as Professor Ungar's replacement.

â Mm-hmm, said Max.

A tic yanked his hand up, and he held the back of it against his lips. Then he brushed three times in a row with exactly the same movement an imaginary strand of hair from his forehead.

I knew that I should ask something. How are you doing? Do you like living here? What problems are there in everyday life? How do the teachers behave toward you? Instead I said:

â Warm today, isn't it?

â Yeah, it's starting to get somewhat warmer again, said the principal. Max, you're on the way to . . . ?

â Main building.

â Yes, we were heading there too, yes . . . Great, great . . .

The whole time I couldn't help thinking:

I feel nothing. Nothing at all. A normal boy. A normal day. No effect. All in the head.

Max nodded and again brushed the nonexistent strand aside.

â I think we'd better get going, then, said the principal, dabbing the sweat from his forehead with his sleeve. Was nice to run into you, Max. Ah, and . . . please tell Herr Mauritz to bring the keys up to me around six o'clock this evening. Because of the bus. And . . .

â Okay, said Max, backing away a few steps.

â Yes, and can you also tell him that the door to the yard still squeaks? He has to take a look at that. Today. Okay?

â Mm-hmm.

Max's backward movement appeared to happen unconsciously, it seemed like a natural reaction, like rubbing your palms together when you've decided something, or shifting from one foot to the other when you're waiting impatiently for something.

â All right, then, okay, said the principal, now taking a few steps back too.

Since I didn't want to remain standing alone in the middle, I followed him.

Max waved again and then marched in his jerky gait accompanied by occasional tics and twitches toward the main building.

â He notices, of course, when the effects set in. The children aren't stupid, when it comes to that. So a sort of etiquette develops, which you learn gradually. For that too it's good to be here at the institute.

Far away a bell rang. Shortly thereafter another student came across the field. He had the same choppy, jagged gait as Max and waved to us from some distance. The gestures were reminiscent of a fencer.

Dr. Rudolph waved back, I did the same. The boy, perhaps thirteen or fourteen years old, stopped, and I was about to start walking to greet him from up close, but Dr. Rudolph held me gently back. The boy also raised his palms in a polite stop gesture.

â New tutor! shouted the principal, pointing at me.

The boy bowed elegantly and then said something I could hear but couldn't immediately understand. He spoke at once quickly and slowly, like the live stream of an Internet video cutting in and out. On that day I encountered for the first time the strange mixed language of the institute children, an extremely fast system of hand signals probably approaching the differentiation of a sign language, combined with a somewhat loud, highly accentuated speech that unnaturally drew out certain syllables. It sounded as if they were articulating through a megaphone that produced a somewhat too-long echo. (Soon thereafter I saw in the dining hall of the institute a student who actually wore a small, light blue megaphone on a black leather strap around his neck.)

After the boy had moved on, the bell rang again and another child appeared.

â They come out one after another?

â There's an order, said Dr. Rudolph. An order . . .

His mind seemed to be elsewhere.

â Robert looked strange, he said. Did you notice his eye?

â No.

â Yeah, he said thoughtfully. It would be stupid if there had been another . . . You know what, I'm going to quickly . . . Just a moment, okay?

He pulled his cell phone out of his pocket and called someone. Because he took a few steps away from me, I couldn't understand what he was saying. I stood alone in my spot and didn't budge. Like a chess piece waiting to be moved. On its own it would never come up with the idea of leaving its square.

The dining hall was a strikingly low-ceilinged but large room. In it were long rows of tables, to which every few yards a chair was attached. You could slide the chairs along the tables like volume controls.

When the principal and I entered, several heads turned toward us. Dr. Rudolph went to a lectern pushed against the wall and flipped an intercom switch.

â Bon appétit, ladies and gentlemen! came from the loudspeakers mounted in every corner of the room.

â Bon appétit, the students replied.

We walked through the dining hall, past the eating noises of the students. I noticed: When the spoons struck the soup bowls, they made a bell-like high sound reminiscent of the soft ringing of a grazing herd of cows.

â And how many Indigo children are in a class? I asked.

Dr. Rudolph's eyes widened for a brief moment. Then he said calmly:

â We don't use the

I

-word here.

â Oh, I didn't knowâ

â No, we generally don't go so much by the perception of the outside world, but more by these young people's own concepts of environment and proximity, which theyâ

â Sorry, I said.

We turned through an open door into a corridor. Here some large-scale pictures hung on the wall. Dr. Rudolph wiped the sweat from his forehead. Then he said:

â Your math professor, Herr Sievert . . . He suggested you to me because you were, he says, a really dedicated student. You have discipline, he said.

â That's nice of him.

â Yes, and I always take such recommendations very seriously, you know. But I do have one question, Herr Sei . . . Setz, right?

â Yes.

â Herr Setz. The question is: Why are you interested in this institute in particular?

â Well, internships are . . . , I began.

Dr. Rudolph's eyebrows rose.

â I mean, it's an interesting challenge to work with young people who . . . who . . .

â So you're saying that it's very hard to get an internship these days. I'm sure that's true. And so you simply took what was offered to you.

â No!

â Please! Dr. Rudolph raised a hand. You don't have to . . . I don't expect at all that you enter an institute like this full of enthusiasm.

â I like to teach.

The principal smiled.

â As I tell all my teachers, he said, they are our future.

â We are?

â No, the children here.

â Oh, of course, sorryâ

â I don't demand enthusiasm from my teachers. They also interact with one another less than in normal schools. All I demand, well, basically expect, is that they realize that these children are the future. They have to ask themselves again and again: What will they grow up to be?

â You mean, we teachers have to ask ourselves that.

â Yes, they, the teachers. Not they, the students. Also, when it burns out and disappears at the start of adulthood, which it doesn't always do, but it does in some cases, it's a backpack that you can't take off so easily. You must be familiar with Edison, right?

â The inventor.

â Yes. He was quite an extraordinary person. Hundreds of patents to his name. In the late nineteenth century he made one of the first talking dolls for children. In the 1880s! It was unfortunately a very scary creature that could say a few words with a tiny wax cylinder in its chest. And to change the cylinder, you had to open the upper body of the doll. So, pretty creepy. After it was played three or four times, the quality of the recording declined so steeply that the doll emitted only a horrible screech, like the faraway shouting of children. After a few months, production ceased, but that didn't discourage him, you know? Edison was never discouraged in his life. Where normal people have that little switch in them, that loss-of-motivation switch, he had nothing. He was fearless, really didn't flinch from anything. In 1903 he killed an elephant from the Coney Island amusement park, an animal named Topsy, by high-voltage electrocution, in order to prove that direct current was better and more efficient than Tesla's alternating current. The procedure was even filmed, he really thought of everything. Killing the elephant wasn't objectionable, because she had already been condemned to death by the zoo beforehand. For years the elephant's trainer had given her lit cigarettes to eat and . . . Everything okay?

â Yes, I just feel . . .

I took a deep breath.

â We're at a sufficient distance, Herr Setz. It's just nerves. Anyway . . . the elephant had a really brutal trainer who abused her for years, and then one day the elephant killed him. At the execution, fifteen hundred people were present and applauded when the elephant fell over. Fifteen hundred people. Well, in life there are rarely happy ends. But at least fair ends. She didn't have to suffer long. It was high-voltage electricity, after all, several thousand volts. Herr Setz?

â Yes?

â Would you like to sit down for a moment? Should we go back into the dining hall?

â No, it's okay, I'm just . . .

â Good, Dr. Rudolph said with a nod. What I'm trying to say: Edison had a special attitude, you know? He was, so to speak,

well adjusted.

For the development of the lightbulb he had to overcome one failed attempt after another, and none of those setbacks affected him in any way. On the contrary, the failed attempts probably even only spurred him on more. He was, at least in that regard, just like nature itself. Nature produced these children. And in a certain sense they are like lightbulbs. At some point, it burns out, they stop burning, the effects fade away. For most of them, in early adulthood. Although . . . there are conflicting schools of thought about that too, but anyway, the details don't really matter here. What's important is the broad, the long-term perspective. What leadership positions will these children one day assume? I often ask myself that.

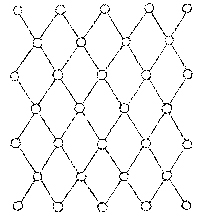

Dr. Rudolph showed me a group photo hanging in a magnificent wooden frame on the wall in the narrow corridor outside the dining hall. In the photo were about fifteen to twenty young men on a soccer field. A few yards away hung a similar picture with young women. Both groups were arranged in a pattern known as a quincunx, something like this:

This design, which occurs everywhere in nature and art, had a very soothing and reassuring effect on me. The young men stood there like rows of trees, nothing could knock them over. The future belonged to them, no doubt about it. It was striking that the distance between them was always exactly the same, on top of that they were all wearing the same clothing, a white shirt with black pants, and the jacketâwhich presumably went with the pantsâthey had slung over their shoulders with their right hands. All were wearing white gloves. The photo seemed to have been taken on a hot summer day.