Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (28 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

Lawrence’s fundamentally nonlinear view of the Arabian theater of operations was not limited simply to making raids on the railroad. He understood that it would also be possible to mount the occasional

COUP DE MAIN

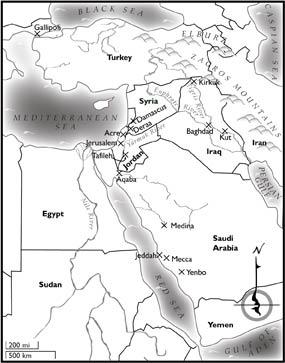

against large, even well-defended, targets. This first of these was the port of Aqaba, where, after a grueling ride, he and an Arab raiding force struck from out of the desert in July 1917. The nearly twelve hundred Turks who had been holding on there against pressure from the Royal Navy were taken by surprise, over a quarter of them killed and the rest captured. Of Lawrence’s force only two were lost—two dead for twelve hundred of the enemy taken out of the fight—a most remarkable result.

This victory increased the Arabs’ faith in Lawrence and deepened their loyalty to him immeasurably; but it also raised his stock among his own people. This was particularly true of Sir Reginald Wingate, the chief British official, or

SIRDAR

, in Egypt who had succeeded Lord Kitchener in this post when the latter went off to fight the Boers. Wingate had initially been leery of Lawrence and sought to limit his activities simply to auditing the use of supplies and munitions given to the Arabs. But in the wake of the spectacular capture of Aqaba, Wingate too became a believer, even recommending Lawrence for the Victoria Cross.

5

After the fall of Aqaba the Arab insurgents were well supplied from the sea by the British. This major new base of operations, now protected by the Royal Navy, became a launching point for a multitude of raids over the course of the following months. Not all of these actions were conducted by camel, as it turned out that armored cars had great mobility over much of the terrain. Lawrence participated in many of these raids; but even as he provided the technical know-how for demolitions—and he was not the only British soldier doing so at the time—his thoughts turned more and more to the possible political aims of the campaign.

For Lawrence, the only truly acceptable outcome of the Arab Revolt was the creation of a free Arab state, stretching from the Gulf of Aden to Damascus, and perhaps even beyond. The declared British position at the time certainly affirmed this idea of self-rule. A message from Britain’s foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, was being air-dropped in leaflets among the Arabs, promising in return for their rising up against the Turks that their success would result in a peace treaty ensuring “independence of all foreign control . . . [and that] the lands of Arabia will, please God, return along the paths of freedom to their ancient prosperity.”

6

But some influential members of the British government opposed this idea and began quietly to undermine it.

Lawrence soon came to believe that Prince Feisal, one of the sons of Husein whose fighters he was advising, had all the qualities necessary to govern wisely. But as the campaign continued to unfold, Lawrence would find, first, that his commanding general, Edmund Allenby, was primarily concerned with using these irregular forces as a means to improve his conventional operations. Later Lawrence would learn that high-level British policymakers had little intention of actually handing over former Turkish territories to the Arabs. The French also opposed Arab independence, intending to stake claims to the areas—largely in modern Syria—where Frankish crusaders had built castles to protect their crumbling kingdoms more than seven hundred years earlier. Ironically, many of these ruined forts had been objects of close study by Lawrence before the war, during his periods of archaeological fieldwork.

Before his ultimate triumph and disillusionment, Lawrence had much more campaigning ahead of him. Allenby’s calls for support had to be heeded, the fractious tribes had to be kept together, and very large numbers of Turkish troops—well in excess of a hundred thousand in his area of operations alone—had to be defeated. Lawrence had the means for doing so in the swift-moving tribesmen. And his beloved high explosives, complemented with machine guns, mortars, and a good number of armored cars, made the insurgents and the small Anglo-French contingent fighting at their side somewhat better armed than their foes.

Yet the reliability of tribal sheikhs was often questionable, and Lawrence found that he had to be his own principal provider of intelligence. This required skillful, covert infiltrations of a number of Turkish-held cities, with Lawrence sometimes taking advantage of his small stature—he was only five feet five inches tall—to veil himself and pretend to be a woman. At other times, in places where Caucasian Turks were more commonly found, he went about more openly. It was on one of these latter-type scouting expeditions, where he was a bit too out in the open, that Lawrence was briefly captured, and suffered one of his greatest personal reverses in the campaign. But before this he was to experience other frustrations, particularly in the in 1917 expedition known as the “raid upon the bridges.”

*

The Great War in the Middle East

Throughout the revolt in the desert, Lawrence’s long reconnaissance missions often found him accompanied by just a few trusted tribesmen. Sometimes these patrols would extend for a thousand miles round-trip. Almost always he would return with useful information to guide the next actions of the Arabs. Sometimes this scouting would take place even while the raiding force was heading toward its intended target, with Lawrence and a few others from time to time moving out ahead. In short, information gathering was an essential task in advance of all missions, and it was one that Lawrence, as a well-trained intelligence officer, took most seriously. But sometimes he fell prey to treachery.

One of the more troubling incidents that bedeviled him occurred in the fall of 1917, when he wished to employ his Arab forces in a raid on railway bridges in the Yarmuk Valley and use this success to spark a rising of the tribes living in that area. Among the locals were Algerian descendants of those who had gone into exile with Abd el-Kader over half a century earlier. The grandson and namesake of the great Algerian insurgent rode into Lawrence’s camp one day just before the raiders set out on this mission, promising “Aurens Bey” their support.

But the Algerian arrived under a cloud of suspicion, as the French intelligence service saw him as likely being an agent of the Turks, an assessment they shared with Lawrence. If this latter-day Abd el-Kader were not a spy, however, his great name could prove useful in recruiting more fighters to the cause. Feisal gave Lawrence this frank measure of the man: “I know he is mad. I think he is honest. Guard your heads and use him.”

7

Lawrence decided to take him along with the raiding party.

In the mission that followed, everything that could go wrong did. The tribesmen whom the raiders met up with distrusted Abd el-Kader and refrained from joining up. Warning shots were fired at Lawrence and his men by potential recruits. Finally, one day Abd el-Kader simply disappeared. His leave-taking, whether out of resentment, guilt, or fear, meant that the local Algerians could not be brought into the operation. Still, Allenby was readying for a major push with his conventional forces—one that would end with the capture of Jerusalem—and Lawrence felt the need to mount a supporting diversion. So the raiders continued on, finally selecting a bridge to be blown up. Now the greater part of the explosives they had brought along were somehow dropped over a cliff by a fearful tribesman during a “friendly fire” exchange among nervous troops, and the bridge action was called off.

Trying to salvage something for all their efforts the raiders used what explosives they had left to derail a train and then attack it. Unfortunately they chose a train filled with hundreds of Turkish troops destined for the defense of Jerusalem against Allenby’s offensive. Once their train was derailed, the troops came rushing out after Lawrence and his sixty Arabs, many of whom were killed and even more wounded, with barely forty making good their escape. The summing up of the whole enterprise was, in Lawrence’s words, “past tears.”

8

If the Yarmuk raid had been a complete failure—perhaps because of the treachery of an infiltrator—what came next for Lawrence was still worse. Just over a week later, on a reconnaissance of Deraa with a lone companion, he was detained by the Turks. They seemed to think he was a deserter from their own army, and Lawrence himself thought he had somehow been betrayed to them by Abd el-Kader. In the event, he kept cover by speaking only Arabic, even under duress, and explained away his light skin by saying he was a Circassian, a member of a tribe from the northwest Caucasus Mountains.

This cover story seemed to work, but by now Lawrence had caught the eye of the local Turkish commander, who fancied him. As Lawrence tells the story, a kind of clumsy wrestling match ensued in which he held his own. At this point the frustrated Turk passed him off to his guards, urging them to teach some manners to the Circassian. They took Lawrence out and beat, whipped, and raped him, leaving him in a shed from which he escaped the next day. He eventually made it back to his comrades and resumed the insurgency with a new grimness. The massacres he oversaw, participated in, or allowed all occurred after this incident.

Some historians and biographers have questioned whether the incident at Deraa ever occurred, given the lack of witnesses to corroborate Lawrence’s account. Whatever the ultimate truth, “Emir Dynamite” was a changed man afterward. Something terrible had happened to him, all in the course of the risky existence he led as adviser, intelligence gatherer, and tactical field commander in very close actions. Lawrence was wounded nine times during the Arab Revolt, several of the injuries being quite serious. Yet nothing seems to have scarred him more than the psychological damage done during his brief detention at Deraa.

Some have seen in this episode the origins of the near-madness and depression that plagued Lawrence in the early 1920s. Others have seen it as a prism through which to examine his sexuality, which to this day seems to remain beyond our ability to categorize definitively.

9

But the unassailable truth worth holding on to is that Lawrence threw himself body and soul into this campaign, leading from the front in battle and going far behind the lines to gather the information needed for each next move. His memoir,

SEVEN PILLARS OF WISDOM

, is subtitled

A TRIUMPH

. This is certainly accurate in military terms. But the price exacted upon Lawrence the man suggests that there was, at a personal level, just as much a sense of tragedy.

*

Tragedy would come at the political level too. That same November, as Lawrence was suffering in the Yarmuk Valley and at Deraa, British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour declared “His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” This policy ran the risk of alienating Britain’s Arab allies—a point that did not escape Turkish attention, as they began to woo the Arabs back—and would prove to be one of the root causes of the nearly century-long dispute over Israel that still bedevils us. In the short run, however, Sir Reginald Wingate was successful with a powerful palliative measure: increasing financial subsidies to the Arabs, who remained allied to Britain. The Arab Revolt thus shored up, Lawrence found himself in a position to engineer some remarkable field operations during the final phase of the war in 1918, when he was called upon to play a key role in the overall military campaign.

At this moment in the war, the operational challenge for General Allenby remained a daunting one, as the Turks continued to fight hard on his relatively narrow front against them in Palestine. After his liberation of Jerusalem at the close of 1917, Allenby was caught in a lull in the pace of the campaign that stretched into the early months of 1918. But events in Europe were now conspiring to complicate efforts against the Turks. First, Russia was knocked out of the war. This development was followed by the redeployment of German troops to the Western Front, where they launched a massive offensive in March. The situation for the Allies appeared gloomy, and in the Middle East the fear was that these developments would both revive Turkish fortunes and fan the flames of a different sort of Arab revolt: one aimed against continued British rule in Egypt and elsewhere.

Jan Smuts, the Boer insurgent who had become a British loyalist, and now sat on the Imperial War Cabinet, arrived to visit with Allenby. Smuts, who would become prime minister of the Union of South Africa the following year, impressed upon Allenby the need to mount a large-scale offensive no later than early May. But because of the pressure the Germans were putting on the Western Front with their Ludendorff offensive, some crack British troops would be taken from Allenby to shore up the situation there. Duly chastened by the seemingly contradictory demand to take the offensive with fewer seasoned troops, Allenby hatched a plan that relied heavily on deception—and would need considerable assistance from Lawrence.