Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (23 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

Despite the distance the Boers covered in the great trek, British attempts to reassert control never ended. One of the Boer republics, Natalia, was snapped up by the British in 1843 and renamed Natal. But in the 1850s the empire did recognize the two most viable republics, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Both were landlocked but prosperous and quite independent-minded. Yet in the face of growing Zulu power and aggressiveness, the Boers were again drawn closer to the British, and the Transvaal was annexed in 1877. The Zulu threat abated after the War of 1879, but early British military reverses in that conflict—particularly the massacre of about a thousand Redcoats at Isandlwana—encouraged the Boers, all fine horsemen and great shots, to think that winning their freedom back might not be so difficult.

This assumption turned out to be correct, as the Transvaal was able to regain its independence in 1881 after the Boers inflicted a most severe defeat on a much larger British field army at a place called Majuba. The British tried to form up and fight using massed rifle volleys while the Boers fired independently and with great accuracy from behind cover, moving in stealthily for their final charge. One of the young Boer fighters was a farmer in his late twenties, Christiaan de Wet, upon whom this battle left a lasting impression about British susceptibility to bush-fighting tactics. When war came again, his would be one of the principal voices arguing against fighting toe-to-toe with the British in favor of a more irregular approach, and he would become the preeminent Boer guerrilla fighter.

From the Battle of Majuba forward, Anglo-Boer relations were never truly repaired. Indeed, they worsened, as in 1884 the British only grudgingly and with loudly voiced dissatisfaction gave up their efforts to ensure better Boer treatment of the Bantu. Then in 1887 gold was discovered in the Transvaal—the largest gold strike in history, and to this day the world’s most important source of the precious metal. Soon all manner of

UITLANDERS

were coming into the Transvaal to seek their fortunes. It was like the Black Hills gold rush in Sioux country a decade earlier in North America, and it caused just as much resentment.

One way the Boers tried to cope with the influx, most of which was British, was to impose strict controls on the interlopers. Among their many constraints, outlanders were even denied the right to vote. These efforts only deepened the hard feelings of the immigrants, who by this point, as Winston Churchill noted, “equaled the native Boers in numbers . . . [and] contributed all but one-twentieth of the country’s taxation.”

2

But the Boers’ efforts to enjoy the commercial gains from immigrant investment and labor while mitigating the potential political and social consequences only made the explosion greater when it finally came.

Tension continued to mount steadily over the next few years, much of it fomented by Cecil Rhodes, who had made a great fortune in diamonds at nearby Kimberley and who wanted in on the gold as well. He became prime minister of the Cape Colony in 1890 and maneuvered continually from

this position toward the goal of outright annexation of the Transvaal. He even conspired to stage a private military invasion in the belief that conquest of the Boers would be welcomed by Queen Victoria—much as Giuseppe Garibaldi’s unsanctioned landing in Sicily in 1860 came to be embraced by Victor Emmanuel. The attack was to be led by a friend of Rhodes, one Leander Jameson, a medical man who had drifted into more mercenary activities. At the last moment Rhodes balked. Jameson, who seemingly missed the signal to stand down, went ahead. But he was no Garibaldi, and the invasion of the Transvaal proved an utter disaster.

The so-called Jameson Raid in 1895 brought the lingering crisis to a new level of intensity and gave it a greater international quality. In support of the Boers, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany publicly congratulated them on defeating the invasion and sent a cruiser from his rapidly growing navy to Delagoa Bay as a signal of his dissatisfaction with Britain’s aggressive behavior. On the other side, Jameson became something of a folk hero to jingoistic pub and saloon patrons in Britain and America—and Mark Twain traveled to the Transvaal to meet with some of the jailed raiders.

Over the next few years some negotiations occurred, but the chasm between the two sides was far greater than even the most skillful diplomacy could have hoped to bridge. For at heart the British goal was reannexation while the Boers’ very firm intent was to maintain their independence. Thus the period 1895–1898 was one of continuing drift toward conflict. By 1899 the days of peace were running out. The Boers were acquiring excellent German Mauser rifles, accurate at ranges over a mile, while the British were sending troops, amassing a force of more than twenty thousand by September of that year.

Curiously the British made a decision to use no soldiers of color, even though their Indian Army had extensive and recent experience in both conventional and irregular warfare, much of it against Afghan tribes. As

L. S. Amery, general editor of the seven-volume

TIMES HISTORY OF THE WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA

, wrote: “It was held inadvisable to make use of any but white soldiers in a war fought between white men in a country where the black man presents so difficult a problem.”

3

The Boers felt the same way, and of course few native Africans were likely to side with them. All that now remained was to see which side would start this whites-only war on the “dark continent.”

The wait ended in October 1899 when the Boers took the offensive with more than forty thousand riders, their numbers a tribute to a conscription system that called upon all males between sixteen and sixty to serve in small

KOMMANDO

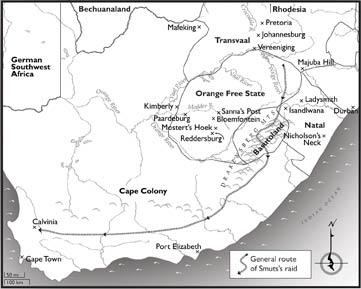

units, usually with 100 to 150 riders in each. Moving swiftly, they struck against scattered British forces, about half their size in the aggregate, driving toward Ladysmith in Natal to the east, Kimberley to the west, and Mafeking in the north. They did not ride south into the Cape colony, reckoning they would rather see the British struggle to come north over great distances. It was eight hundred miles from Capetown to Pretoria, and the lack of roads would tether the British to easily disrupted rail lines.

After their first rush forward in the opening months of the war, the Boers—too few to take cities by storm and lacking the heavy artillery needed to batter them into submission—were slowed by the need to besiege their three main objectives. Yet when the first British relief forces under the unimaginative Sir Redvers Buller came along, simultaneously but separately, to lift these sieges, the Boers dealt roughly with them. The series of reverses, occurring from December 10 to 17, 1899, came to be known in Britain as “Black Week.”

Just a short while earlier, de Wet had played an important role in a great victory in Natal, cleverly outmaneuvering a British force five times the size of his

KOMMANDO

at Nicholson’s Nek. There, striking at them much as Forrest would have, de Wet took a thousand prisoners, the largest surrender of British troops in a century. It was a reverse that affected British morale as badly as any of the defeats in December.

4

In the wake of his victory, de Wet was promoted to general in December 1899 and spent Black Week making his way from the Natal front to help out General Piet Cronje in the Orange Free State. Cronje was facing off against a fresh and much larger British force under a new and much better British commander, Field Marshal Lord Frederick Roberts, an old India hand now at the head of a concentration of more than seventy-five thousand troops. Cronje hoped to confront this new threat directly while de Wet sought to disrupt Roberts’s lines of communication and supply. In the early days of 1900, both approaches were pursued.

Cronje kept most of his forces together—more than four thousand men—preparing for a defensive battle against the more numerous invaders. With a few small

KOMMANDOS

, de Wet rode about raiding here and there, diverting perhaps a third of the British main force. But this still left nearly fifty thousand troops coming down upon Cronje. When de Wet warned him of this, suggesting a timely retreat, his superior dressed him down in front of others, pointing toward the British and asking “Are you afraid of things like that?”

5

Cronje’s stubbornness led to his whole force being trapped at Paardeberg.

De Wet cobbled together a relief column of some thousand riders from a number of

KOMMANDOS

and attacked a vulnerable point in the British cordon, opening a narrow escape route. He held it against all British counterattacks for almost three days. But Cronje, still hoping for a head-on firefight, reluctant to leave his guns and supplies in a headlong retreat, and perhaps even in shock over what was happening, refused to move. De Wet finally had to retire, and Cronje and his whole force surrendered on February 27, 1900, the nineteenth anniversary of the victory at Majuba in the first war with the British.

Now the Boers had suffered their own crushing equivalent of Black Week, and Roberts was swift to seize the moment and press the offensive. But Cronje’s capture led to de Wet being given overall command in the Free State, and now he intended to make mobile hit-and-run raiding the core of his concept of operations. In the events that followed, de Wet would cause endless trouble for the British advance, delaying a huge force with a relative handful of riders. Much like Nathan Bedford Forrest in the American Civil War, de Wet focused on attacking communications and transportation infrastructure. Like Forrest too, de Wet was indefatigable, almost always at the forefront of the fight. One firsthand British observer of the war, Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, whose account of the Boer War was a massive best-seller in Britain, summed up how de Wet was viewed by the enemy: he was known simply as “the great de Wet.”

6

And Conan Doyle made this assessment even before witnessing any of de Wet’s more remarkable accomplishments during the war’s later phases.

*

After the crushing defeat at Paardeberg, the Boers tottered on the brink of capitulation. Roberts certainly thought the war was won, and on March 15, 1900, he offered amnesty to all Boer fighters willing to return to their farms. Quite a few took him up on this offer. But many Boers remained in the field, fighting in small rearguard actions here and there. De Wet, however, sought ways to take the strategic offensive once again. But instead of fighting the British straight up, as the Boers had chosen to do at the outset of the war, he realized that, as Thomas Pakenham has observed, “the overwhelming numerical superiority of the British now demanded new strategy from the Boers. Indeed, the commando system was best suited not to large-scale, set-piece battles, but to smaller-scale, guerrilla strikes.”

7

Major Actions of the Boer War

De Wet now proceeded to unfold this new strategy in a series of sharp actions that disrupted the British advance. First, at a place called Sanna’s Post, de Wet ambushed a column of several thousand cavalry and mounted infantry, attacking them on one flank to drive them into the rest of his small force, which he had positioned to lie in wait along their anticipated line of retreat. The result: British losses of nearly two hundred killed and wounded, and more than four hundred prisoners taken. De Wet lost three killed and five wounded. The British could not believe that a poorly educated farmer-turned-soldier of middle years was capable of such sophistication, and they soon spread the false rumor that Captain Carl Reichmann, the American military attaché in the field with de Wet as an observer, had actually conducted the battle.

8

Just days after the action at Sanna’s Post, de Wet’s scouts informed him of a slow-moving column of some five hundred British infantry heading in the direction of Reddersburg. De Wet pounced on them swiftly, augmenting his force by re-recruiting some of the Reddersburg men who had just weeks before accepted Roberts’s amnesty offer. De Wet soon had the British trapped on a ridge known as Mostert’s Hoek, where his forces inflicted fifty casualties and captured all the remaining British troops. Thus a second remarkable victory was achieved in the span of one week running from late March to early April 1900.

For the Boers these victories were a tonic, shoring up both their morale and their strategic position, and giving Roberts serious doubts about how and whether to resume his advance. Byron Farwell has argued that de Wet’s actions were the key to sustaining the Boer effort in the aftermath of the catastrophic defeat at Paardeberg: “The war might indeed have been brought to a close as quickly as Roberts anticipated had it not been for one of the most remarkable men to emerge from the Boer ranks, a leader who did truly become a legendary figure in his own time: Christiaan de Wet.”

9