Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (22 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

By the close of 1872 most of the increasingly harried Chiricahua had chosen to make peace and were on a reservation. They had no solution to the concept of operations that Crook had pioneered, which took away their sanctuaries and allowed them no respite from pursuit. Cochise, terminally ill, probably with cancer, made his sons promise to keep the peace. Geronimo also reconciled himself to reservation life. Yet his desire to raid remained strong, and it seems he sometimes went off to attack Mexican settlements south of the border. For Crook this was a time of mopping up, establishing reservations for tribes that wanted to be off on their own, and striving hard to deal justly and humanely with the many administrative details of overseeing a conquered people. It was a peaceful interlude that would not last.

*

In the spring of 1875 President Grant issued his next challenge to Crook: he was to deal with the Sioux and other Plains tribes who had massacred Fetterman and forced the closure of the Bozeman Trail and its protecting forts some years earlier. Always sensitive to the Indians’ grievances, Crook began by devoting his efforts to expelling the whites who had gone into the Black Hills searching for gold. This was sacred territory for the Native Americans that had been ceded to them by treaty. Thus Crook tried to keep the peace; but the following year the Indians, feeling a strength that came with cross-tribal unity, moved freely, and with violence, beyond their reservation limits. A renewed war was soon under way.

The plan of battle against the Sioux-Cheyenne alliance, which could field some five thousand warriors overall, was designed by Sheridan as a three-pronged assault, not unlike General Jeffrey Amherst’s ranger-led campaign against Montreal in 1760. From the north, Colonel John Gibbon led a force from Fort Shaw in Montana. Custer, nominally under the control of Brigadier General Alfred Terry, rode at the Indians from the east, starting at Fort Lincoln in North Dakota. Crook advanced from the south, beginning in Cheyenne, Wyoming. It was a conception of Napoleonic sweep; but the Indians held what the great strategist Baron Jomini called the “interior position.” That is, they could mass against one or another of these columns, defeat it in detail, then move on to the next. Frederick the Great of Prussia had done this brilliantly in the eighteenth century. Now Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse would do the same.

They struck first against Crook’s column of about a thousand—mostly bluecoat troopers but with a few hundred Crow and Shoshone fighters alongside them, as the Gray Fox now always sought tribal allies. In the fight at Rosebud Creek, Crook’s Indian allies saved him from disaster when the Sioux and Cheyenne struck swiftly and in mass. It was something they almost never did, and they caught Crook by surprise. As one historian has described the Indian fighters, “they pressed the battle with a ferocity that astonished and disconcerted the soldiers and tested the skill of their officers.”

10

Crook held on, and at the end of the day the Indians rode off; but the bluecoat advance from the south had been halted. Crook had to take his wounded to hospital and needed reinforcements before resuming his advance.

This strategic victory allowed Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull to turn next to Custer, whose impetuosity soon got him into terrible trouble. This time, unlike during the Civil War, Crook could not come to his rescue. On June 25, 1876, Custer and five troops of the famous Seventh Cavalry—more than two hundred men—were wiped out at the Little Bighorn. The Sioux and Cheyenne next turned to deal with Gibbon’s column. This time they used more irregular tactics in thwarting his advance through Yellowstone country. By September Gibbon was withdrawing to wait for reinforcements and the renewal of Crook’s offensive.

Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull now seemed to believe that the war was over, or at least that they had once again earned some years’ respite from white encroachment. Crook and Colonel Nelson A. Miles, another enterprising Indian fighter, soon showed them the errors of their thinking. Together these officers crafted plans for a winter campaign of movement against the tribesmen, who had great difficulty fighting in winter weather. Crook hewed to his basic principle of allowing no respite to tired enemies. As the historian Russell Weigley put it, he was “always driving the Indians toward exhaustion.”

11

Miles demonstrated that he was every bit Crook’s equal in this kind of fighting.

12

Indeed, an increasingly bitter rivalry between the two would soon surface. Sitting Bull saw no recourse but to escape into Canada, from which he would return to surrender. Crazy Horse, responding to an appeal from Crook, surrendered in the spring of 1877. There was talk that he would join Crook in fighting Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, but this never came to be. Crazy Horse rode off his reservation one day, then died in a scuffle—perhaps bayoneted by a bluecoat—when he returned of his own accord.

In the campaign against the Nez Perce that followed over the summer and fall of 1877, Crook played no real part. He had been detailed off to Chicago to try to quell labor unrest there. But the press, unhappy with the slow pursuit of Chief Joseph, whom they labeled the Indian Napoleon, clamored for Crook to replace Oliver O. Howard, who showed little of Crook’s penchant for hot pursuit.

13

In the end, Joseph eluded Howard but was trapped by Miles. Crook thought his Indian-fighting days were over. They were not.

*

Almost as soon as Crook left Arizona, the private contractors who took over management of the Indian reservations began to undermine the peace with corrupt practices. They would receive funds from Washington to cover the costs of running the reservations but would shortchange the Indians with inadequate food and other services, then pocket the rest of the government money. This scheme prompted rebellious behavior on the part of the Native Americans. It took years to blossom into a fully renewed insurgency, but it came nonetheless.

Geronimo was the key Apache leader in this last great rising of his people. In the late 1870s he had run off the reservation to engage in raiding—to provide for his people—and then come back. But in September 1881 Geronimo killed the chief of the reservation police and defeated a detachment from the Sixth Cavalry. He remained on the warpath thereafter, guiding a series of raids in which he was joined by a new generation of talented lieutenants, including an exceptionally gifted one named Chato.

For more than a year, into the autumn of 1882, the Apaches held the nearly uncontested initiative. They struck outlying settlements and wagon trains at will, then retreated into northern Mexico, enjoying a haven in the Sierra Madre Mountains. But Crook had returned to Arizona in September of that year, and things were soon to change. After his customary period of study and contemplation, he acted in a way that was both familiar and new: he recruited friendly Apaches to fight Geronimo, but he refrained from creating a large number of small flying columns. Instead there would be just one, and it would go deep into Mexico after the Indians, a move enabled by a “hot pursuit” treaty between the United States and Mexico that had just been signed to make such actions legal.

14

After careful preparation, much of it consisting of finding mules of the highest quality, Crook crossed into Mexico in pursuit of his foes on May 1, 1883. His force consisted of only 250 fighters—200 of them friendly Apaches—less than half the size of Geronimo’s warrior band. It was a daring move that put Crook’s theories about the power of keeping on the move and the value of native allies to the ultimate test. And he passed it, for just a few weeks into this small offensive, Crook and his men came upon Geronimo’s main camp—an event somewhat like the French finding Abd el-Kader’s

SMALA

—and overran it in a short battle.

Geronimo was not there at the time of the raid, but others in the band who were nearby began to come in and surrender to Crook, whose feat and personal bravery had greatly impressed them. In the days after the battle, more than two hundred Apaches surrendered to him. Still he remained at the camp, waiting for Geronimo. When the great Apache chief arrived, Crook went out alone to meet him and his remaining warriors. This act of bravery was also respected, and in the coming days Crook and Geronimo negotiated a peace. Most of the Apaches would return to the reservation with Crook, but Geronimo and some other warriors would come in later so that they could first round up their cattle and bring the herd back with them to feed their people.

15

Upon his return Crook, whom the press had given up for dead, was praised for his success but castigated for having trusted Geronimo to turn himself in. Retractions were necessary when the great Indian leader returned to the reservation, driving his cattle before him. And for the next two years there were no Apache attacks on troops or settlers in Arizona or New Mexico. It seemed that peace had come.

It was interrupted in the spring of 1885 when Geronimo, fearing arrest for past misdeeds, left the reservation once more.

16

His concern was unfounded, but it set off one last round of raiding. Crook viewed Geronimo’s action as breaking his word of honor, and took steps to secure his territory but refrained from a new manhunt. His superiors were enraged by Crook’s seeming nonchalance in the face of the renewed threat. General Sheridan now came to recommend abrogation of the treaty and removal of all Apaches to Florida. Crook, feeling that his promise to the Apaches was being broken, asked to be relieved.

His replacement was his old rival Nelson Miles, whose first act was to disband the Apache scouts. They had done much to bring peace and security to the territory but were now to be transported with the rest of the Apaches. Miles’s next move was to pull together a force of some five thousand troopers to protect settlements and ride about in flying columns in search of Geronimo. His concept of operations failed completely against his enemy’s ability to raid in Arizona and then return to the mountains of northern Mexico. It became clear that Miles would not succeed unless he adopted Crook’s method of going into the Sierra Madre in pursuit.

Eventually Miles ordered one of his subordinates to do just this. Geronimo was found and surrendered for the last time in September 1886, based on the assurance that he would not be punished further. But he and his people

WERE

punished. They were separated and transported east. Crook, now a much-honored major general with his headquarters in Chicago, fought for their release unsuccessfully for the rest of his life, which was all too short. He died of a heart attack in 1890 at the age of sixty-one. In the same year the official census declared there was no longer a “contiguous frontier.”

VELDT RIDER:

CHRISTIAAN DE WET

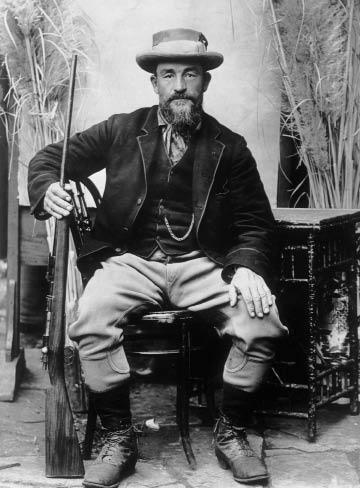

Bundesarchiv Bild

At the same time the Indian tribes of the American West were mounting their fierce resistance to the onrush of settlement and development, a number of South African tribes were doing the same, most notably the Bantus and the Zulus. Like the Indians, they too had sterling military qualities, particularly the Zulus. But there was one big difference between the situations: in South Africa one of the “tribes,” having settled there more than two hundred years earlier, was white.

In 1652, the start of an era in which the Netherlands would hold its own in a series of naval wars with Britain, the Dutch East India Company established a way station at the southern tip of Africa. The settlement grew and expanded over the years, with the original Dutch settlers joined by French and German Protestants. Together they came to call themselves Afrikaners (People of Africa) and developed a variant of the Dutch language, Afrikaans, that all spoke. They drove the Hottentot tribe from the growing and grazing lands that they coveted, and prospered uninterrupted until the early nineteenth century.

At this point Napoleon Bonaparte brought Britain into their lives, seemingly to stay. For when the Netherlands came under the control of the French Empire in 1806—Bonaparte’s brother Louis was made king of Holland—the Royal Navy went off to protect the Cape colony in the name of the deposed Dutch monarch. Somehow South Africa was never returned, being formally annexed by Britain in 1814, perhaps a partial reward for its long struggle against Napoleon.

Tensions soon rose between the British and the Afrikaners, also called Boers from their word for farmer.

1

The principal problem was that the British were opposed to the Boers’ enslavement and poor treatment of indigenous African tribes. Bridling at what they considered a most undue intrusion into their way of life, several thousand Boers set off on a “great trek” north from the Cape across the prairies (the

VELDT

, or field). During the period 1835–1837, they established a multitude of small, free republics where they could do as they wished—whereas their Boer brothers who remained in the Cape had to toe the British line.