Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (40 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

Like Greene against the British regulars, Giap proved as yet unable to win a pitched battle against the French. His Vietminh did manage to raid many remote outposts, generally killing or capturing their entire garrisons, with French dead and missing exceeding seven thousand in this phase of the fighting. But the Vietminh suffered heavy losses when, during 1950 and through the summer of 1951, they shifted to attacking the French in better-prepared positions, incurring some twenty thousand casualties of their own. The insurgents could not sustain such losses, given that these costly conventional attacks were now being regularly repulsed.

It was a dark, low period in Giap’s life. Ho soon called a meeting of the Communist Party to discuss the situation and even advanced a motion to relieve Giap of his command. But then Ho turned matters around by arguing eloquently against his own recommendation, and the political bureau voted to keep Giap in charge of the Vietminh. Why had Ho acted in this way? Cecil Currey thinks that Ho’s support for Giap never wavered, but that he had put forward this motion to “to allow discussion and criticism and to clear the air of any developing movement to unseat Giap.”

6

He may also have stayed with Giap to keep Chinese influence over his insurgency at a minimum.

Ho’s stratagem worked. With his bureaucratic flanks now shored up, Giap could concentrate once again on resuming the offensive against the French. But he intended to do so in a different way, rekindling his unique, skillful blending of Mao’s guerrilla guidance and Napoleon’s notions of swift, multiple movements to dislocate enemy forces. Still, the challenge was a stern one. The French were flush with their victories in the field and now enjoyed considerable American material support. Giap had to call on all his skill and daring in the fighting that followed.

*

After the failures of 1950–1951, Giap returned largely to hit-and-run tactics, both to keep the French off balance and to restore the morale of his own cadres. The insurgents’ success in rattling their foes may be measured in the rise of French forces to roughly two hundred thousand troops by 1953, with nearly five hundred thousand friendly Vietnamese serving on their side as well. All this was happening while Giap could muster perhaps a hundred thousand fighters, including his hard-core cadres and local, village-based units. To their numerical superiority the French added increasingly active airpower and riverine “naval assault divisions.” In the view of the great chronicler of this conflict, Bernard Fall, the small, heavily armed boats of the

DINASSAUT

were perhaps the most innovative French advance in counterinsurgent methods, as they made it possible to penetrate the jungle and mount amphibious raids deep into what had previously been Vietminh sanctuaries.

7

In the sharp firefights that characterized these operations, the French often came out ahead.

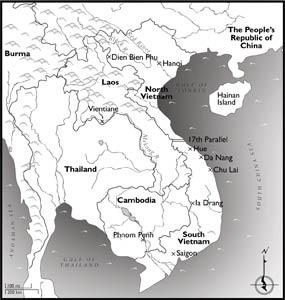

The Southeast Asian Theater of War

Despite effective counterpunches such as those landed by the

DINASSAUT

, when Giap made a point of shifting to the Napoleonic notion of striking at multiple targets from several directions at once, he retook the initiative. By mounting small-scale attacks throughout the country, he induced the French to disperse half their own forces and about three-fourths of the friendly Vietnamese—just under five hundred thousand troops in all, counting both French regulars and local levies—to garrison duties in cities and villages throughout the country. This considerably reduced their offensive striking power.

But Giap was not satisfied simply with blunting French prospects in this manner; he wanted to take the strategic offensive. Thus he persuaded Ho to agree to an invasion of Laos, a part of their Indochinese colonies that the French had thought was safe from insurgent threats. It was a stroke that opened up a whole new threat the French felt they had no choice but to counter, as many Laotians were sympathetic to the Communists. In November 1953 the French commander General Henri Navarre sent ten thousand troops to a Vietnamese valley town surrounded by rough country very near the Laotian border, which had long been a crossroads for trade between Burma, Siam (Thailand), and China. Its name: Dienbienphu, which in Vietnamese means “the arena of the gods.”

Navarre believed that he could both cut off supplies to Vietminh forces operating in Laos and provoke the enemy into a pitched battle there. For his part, Giap believed firmly that beating the French at Dienbienphu would break their will to continue fighting, so he concentrated half his total combat forces in this area, roughly fifty thousand troops. Giap also mustered some twenty thousand bearers to keep the force supplied and haul his heavy artillery into position—echoing von Lettow’s reliance on porters in German East Africa during World War I. During this time the Vietminh began to make large-scale use of bicycles, not pedaling them along trails but rather loading them with hundreds of pounds of rice or ammunition and

PUSHING

them. The effort was nothing short of monumental.

For their part, the French saw that the fight they had provoked was coming. They now relied on resupply and reinforcement from the air, their garrison at Dienbienphu growing to about seventeen thousand by the time the siege was in full swing. French attack aircraft inflicted regular losses on Vietminh supply convoys but could not interdict the overall flow. Bicycles easily steered around bomb craters, which on dirt roads could be quickly filled in anyway. Aerial attacks had even less effect on Vietminh artillery emplacements, skillfully sited as they were on inner slopes instead of hilltops, and well protected by antiaircraft guns supplied by Mao. This positioning brought Giap’s two hundred big guns much closer to their targets and allowed them to be aimed over open sights.

The senior French artillery officer at Dienbienphu, Colonel Charles Piroth, had vowed that the Vietminh could never move heavy artillery into the hills above them. But when the enemy barrage opened up on the evening of March 12, 1954, and was swiftly accompanied by massive infantry assaults that caused at least a thousand casualties by midnight, Piroth pulled the pin on a grenade and blew himself up. The rest of the French fought on skillfully, holding off the attackers and in some places throwing them back in hand-to-hand fighting. After three weeks of conventional-looking frontal assaults, the Vietminh had lost ten thousand men, about 20 percent of their total combat force. Yet the French garrison held. It was a moment that kindled memories of the disastrous, failed Vietminh offensives of 1951 and, in the words of the historian Michael Maclear’s understatement, “caused General Giap to pause.”

8

Giap knew that he must change his approach if the French were to be defeated in this Southeast Asian Verdun. His solution was to call off all massed frontal assaults in favor of a far more irregular approach: the Vietminh would “dig their way” to victory. Over the next weeks his troops dug more than one hundred miles of trenches, coming at the French simultaneously from every point of the compass. When they came close to the defenders’ positions, they mounted raids, mostly at night. One by one the French strong points were lost to this “creeping swarm.” In Giap’s own words, the battle had become a straightforward matter of “gnawing away at the enemy piecemeal.”

9

By late April 1954 it was clear that the fall of Dienbienphu was only a matter of time—a very short time. French leaders in Paris strove desperately to persuade the United States to intervene with aerial bombing before all was lost. President Eisenhower considered joining the fight in this manner and even contemplated the use of tactical nuclear warheads, under the code name Operation Vulture. But he was strongly opposed in Congress by a key Democratic leader there, Senator Lyndon Johnson. Ironically, it was Johnson as president who took the United States to war in Vietnam a decade later.

10

Britain’s prime minister Winston Churchill, when consulted by Eisenhower, argued strongly against trying to solve the Vietnam problem with heavy bombing. Churchill had been around irregular operations since the Boer War more than half a century earlier, and was himself overseeing counterinsurgencies in Malaya and Kenya at the time. He preferred more subtle military approaches and greater reliance on the Vietnam peace negotiations about to get under way in Geneva. Of the great British leader’s abhorrence to the idea of aerial bombing in this case—perhaps even with atomic weapons, the French journalist and historian Jean Lacouture noted: “Churchill, who was a fighting man, thought it impossible, extremely dangerous.”

11

The French surrendered at Dienbienphu on May 7, 1954, their remaining eight thousand soldiers marching off into captivity. Giap’s forces had suffered casualties in excess of twenty thousand killed and wounded, more than double the French losses. Far from being the “arena of the gods,” Dienbienphu had become, in the words of Bernard Fall, “hell in a very small place.”

12

The day after the French surrender, peace talks opened in Geneva. When they concluded some ten weeks later, Vietnam had been divided in half at the Seventeenth Parallel. Ho, Giap, and their comrades would rule in the north, the seemingly Western-friendly former emperor Bao Dai in the south, until national elections took place no later than July 1956. In the event, the United States came to strongly oppose holding any such elections—for it was clear that Ho would win them—and tensions slowly grew, along with the sporadic but sometimes spectacular violence that led to the resumption of all-out war.

During the decade of relative calm between the end of his fight against the French and the start of the war with the Americans. Giap was busy expanding the North Vietnamese army to 350,000 troops, and building local militias that came to total more than 200,000 members. His second wife, Ha, made a special point of encouraging him to slow his pace, to take real vacations from time to time. She succeeded in cultivating Giap’s inner warmth, so much so that another general, Nguyen Chi Thanh, once said to her: “Giap still has the attitudes of a bourgeois because of you.”

13

Perhaps this was so. But given his skillful, sustained preparations for war—this time against the United States with its incomparable airpower—it is hard to see any sort of bourgeois softness in him. In the years of conflict that all too soon came again, his American opponents would come to see only the flash of his steel.

*

Given that the American Cold War strategy of containing the spread of communism enjoyed wide bipartisan support, it is hardly surprising that Lyndon Johnson decided to intervene to stop Ho and Giap from taking over South Vietnam. The only real question was

HOW

to do it. President John F. Kennedy had emphasized the use of Special Forces to help train the Vietnamese to defend themselves. Even after Kennedy’s assassination and Johnson’s ascension to the presidency, military thinking about intervention was still small in scale. The violence rising in the South was insurgent and terrorist in nature, and was fomented for the most part by the armed wing of the People’s Revolutionary Party, the National Liberation Front—or, as its fighters came to be known, the Vietcong.

Giap, the hero of the war against the French, now found himself fighting on two fronts: one against the American-supported regime in the South and one against his internal rivals. Chief among the latter was General Nguyen Chi Thanh. In 1960 he seems to have succeeded in convincing Ho to replace Giap as commander of insurgent operations in the South. As always, however, Ho may well have been playing a deeper game. By taking Giap out of the picture, at least temporarily, he was better able to portray the Vietcong to the world as an independent group of freedom fighters—though, as Cecil Currey notes, Hanoi “controlled the NLF lock, stock, and barrel.”

14

The campaign in the South unfolded much as the insurgency against the French had. Cadres were cultivated and local fighting units formed up, and acts of violence against remote government outposts were skillfully blended with occasional attacks in cities. While it had by now become clear that the United States would never allow elections that might result in unifying North and South Vietnam, making war the only solution in Ho’s eyes, the declining legitimacy of the government in Saigon only fueled the Communist cause.

The situation was further complicated by the erratic policies of a U.S.-favored strongman, Ngo Dinh Diem, who had rigged elections in 1955 to overthrow Bao Dai and commenced several years of his own incompetent rule. He was ousted in a military coup in November 1963 and executed. Thereafter South Vietnam was subjected to a series of unsuccessful would-be dictators. For Ho and Giap, the death of Diem and the chaos in the Saigon government prompted an escalation of their military campaign. But Giap’s great rival in the North Vietnamese Army, Nguyen Chi Thanh, remained the commander in the south, and was praised by the Politburo in Hanoi for his preference for large-scale pitched battles. Giap, who had failed in using this approach against the French, strenuously opposed this policy, but was overruled.