Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (20 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

In the near term Forrest was much remembered for the massacre at Fort Pillow and his Klan affiliation. But his military reputation grew despite these blots, receiving a major boost in a famous article published in 1892 in the

NEW ORLEANS PICAYUNE

by the great British expert on irregular wars, Field Marshal Joseph Viscount Wolseley, who praised in particular Forrest’s “acute judgment and power of perception.”

23

Ever since, he has become a central character in American folklore—racist demon to some, military genius to others, and, even more, a tragic hero of the South’s “Lost Cause.”

24

These views, each of which has some merit, nonetheless fail to get at the heart of his contribution to the evolution of irregular warfare: his emphasis on simultaneous multidirectional attack and his belief that the greater the size of the enemy, the greater his vulnerability to disruption of his communications and transportation infrastructures. Instead of being remembered by his aphorism about getting there first with the most, Forrest—who almost never had a numerical edge over his opponents, save for brief, very localized tactical situations—should be known as one of the fathers of swarm tactics. He demonstrated, for the first time in modern war, that whatever new power industrial advances conveyed to militaries, they also opened a host of new vulnerabilities. That should be seen as the insight that has informed insurgents, commandos, and terrorists ever since.

Whatever his personal flaws, Forrest was a quintessential master of irregular warfare, one who built substantially on the methods pioneered by Denis Davydov and Abd el-Kader. He should also be seen as the progenitor of a number of skillfully conducted irregular campaigns waged in the 150 years since he and his troopers held sway. One does not have to look far to pick up the trail of his intellectual legacy. Another American master of irregular warfare, George Crook, would soon be relying regularly on

Forrest-like ways in the final series of campaigns launched against the Indians of the West who stood in the way of American “manifest destiny” during the decades immediately after the Civil War. That the Native American resistance also relied on irregular tactics and strategies would make for a compelling clash, testing the skills on each side to the limit.

GRAY FOX:

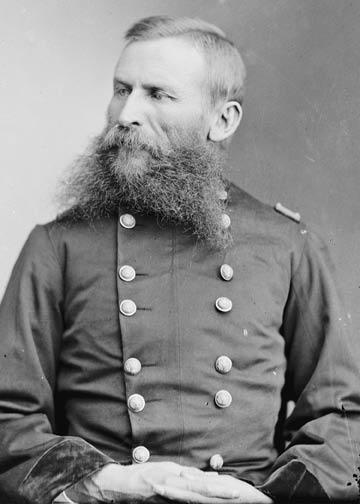

GEORGE CROOK

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

As the American Civil War was winding down, the final phase of the Indian Wars was gearing up. While federal forces had been focused on fighting the Confederates, the still-free Native American tribes west of the Mississippi River had been able to stem the tide of white settlement—and in places had reversed it, as the Apaches did for several years in Arizona under their great leader Cochise. But once the Union was fully restored, the fundamental strategic problem of the Indians resurfaced: they were simply too few against too many. This numerical inferiority drove the Western tribes to fight in irregular ways, with hit-and-run raids and ambushes their most common tactics. There was clear precedent for this in American history, as we saw in the brutal wilderness war waged by Native Americans and whites during the eighteenth century. In the first half of the nineteenth century the pattern continued, with the Seminoles of Florida mounting a heroic, protracted guerrilla resistance under Osceola that lasted into the early 1840s. But their defeat was inevitable, especially once the American military began to target crops and villages, a brutal success formula.

The Indians of the West may not have been aware of all this history, but they quickly learned that the coming of white settlers meant the end of their way of life. Cochise, for example, had at first tried to live peaceably with the settlers during the 1850s, even having his people contract to provide firewood to them. For decades he had been able to hold off the Mexicans who tried to make incursions into his people’s lands; but the Americans who displaced them after the 1846–1848 war seemed likely to pose a tougher challenge. So he decided to begin relations with the new interlopers in a more conciliatory manner.

But cultural misunderstandings, cupidity, and mutual mistrust all contributed to the outbreak of violence in Arizona. As did treachery, the most egregious instance occurring in February 1861, when a young and inexperienced federal officer lured Cochise and several family members to a meeting, ostensibly to talk about cattle rustling and the recent kidnapping of a white child, but then attempted to arrest him on the spot. Cochise escaped the trap, though wounded in the process, and several of his family members were taken prisoner. He retaliated with a raid on a wagon train and the taking of hostages, which he killed when his own people were not released. In retaliation Cochise’s brother and two nephews were executed. The war had begun.

Cochise and the Apaches mounted punishing raids throughout the Civil War years and persisted even after. And they were hardly alone in resisting white incursions. Other Indian tribes farther north were also beginning to come into conflict with homesteaders who wished to settle on their lands, prospectors looking for precious metals, and still others who passed through on their way west, cutting a swath of environmental degradation along the way. So the Sioux, the Cheyenne, and other tribes began to fight for their lands and their ways of life. Inevitably their resistance prompted the coming of the American military, whose job was to protect the innocent—and also to subdue the Indians. All too soon, to use the military historian S. L .A. Marshall’s phrase, this part of the West became a “crimsoned prairie.”

1

Initially the Indians got the better of the whites on virtually all fronts. The Apaches were better desert and mountain fighters, taking every advantage of familiarity with their home terrain. The Sioux, Cheyenne, and other Plains tribes were magnificent horsemen who were able, again and again, to combine speed of movement and stealth to their advantage. White settlers offered a wide range of slow-moving, often static targets, not unlike their eighteenth-century forebears who first began to push inland from the East Coast. Further, while the Native American tribes were still basically Stone Age peoples, thanks to illicit arms traders they soon possessed advanced weapons, especially the quick-firing repeating rifles now coming into production. Thus it was not unusual for the Indians to outgun the bluecoats in battle.

The tribes also had several great insurgent leaders. In the harsh desert-and-scrub environment of the Southwest, Cochise was joined by other Apaches like Mangas Coloradas (Red Sleeves) and Geronimo, among others. Mangas was his father-in-law; Geronimo was with Cochise from the start of his campaign in retaliation for the trap that had snared his family. Their brilliance as hit-and-run raiders was demonstrated over many years of hard fighting, scarcely dimmed by the reverse at Apache Pass where they once tried unsuccessfully to engage in a toe-to-toe, massed fight. Mangas’s reputation remained untarnished even in death, as his fall came from a desire to negotiate peace. He fell into a trap similar to Cochise’s—but Mangas didn’t escape.

Farther north, the Plains Indians were also brilliantly led. Their great leaders included the mystic Crazy Horse and the visionary tribal unifier Sitting Bull. Together they would bring about the spectacular downfall of George Armstrong Custer in the summer of 1876 at the Little Bighorn. In the mountains and forests of the Pacific Northwest another remarkable leader was Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, who would one day confound his bluecoat pursuers during the course of a magnificent thousand-mile fighting retreat that very nearly saw him and his people escape to Canada.

In short, the terrain, the weapons technology available to the tribesmen, and the high quality of their chiefs were factors that all pointed to the need for exceptionally skillful leadership on the part of federal forces. Instead, at the outset the Indians confronted a foe who featured a mixed bag of conflicting traits. Many of the government soldiers were battle hardened, but just as many were war weary. Even with post–Civil War reductions in forces, their numbers were quite large enough for the tasks at hand, and securing the frontier was virtually the only mission of the U.S. Army. But its leaders’ tactical notions, reflecting their dominant Civil War experiences, were far more oriented to stand-up fights than to irregular operations.

All these factors combined to keep the initiative with the Indians for several years after the Civil War. In the North the signal event was the slaughter of a small force that had ridden out of Fort Kearny in the Wyoming Territory under an impetuous officer, one Captain William J. Fetterman. He had bravely earned a colonelcy during the Civil War and held the Indians in contempt, particularly what he regarded as their cowardly hit-and-run tactics. He was fond of saying that with just eighty troopers he could ride right through any opposing Indian force. Naturally he soon fell into a simple false retreat trap, and he and his eighty men were killed just days before Christmas 1866.

Throughout 1867 desultory fighting continued, and the bluecoats began to learn from their hard experiences against the Sioux and the Arapaho on the Plains. But not fast enough for President Andrew Johnson, who sent a peace commission to Wyoming in the spring of 1868 to try to end the fighting. The agreement signed in May required federal forces to close their forts along the Bozeman Trail, which ran right outside the gate of Fort Kearny. The Indians burned the forts immediately after they were abandoned. The tide of white settlement had been stemmed.

In the Southwest, the situation was just as bad. The Apaches were able to move about and strike small communities and wagon trains at will, for a while breaking the trail links between Texas and California. Federal forces had little luck engaging the Indians or protecting the settlers. This despite the fact that from 1865 to 1868 Cochise had his hands full on another front, fighting the incursions of the Tarahumara, Yaqui, and Opata Indians who were being pressured northward by Mexican forces into Apache territory.

2

Cochise dealt with this problem, then turned his full attention once again to the whites, unleashing an absolute reign of terror.

Many settlements and mining operations were soon abandoned, as none seemed beyond the reach of Apache raiders, and the federal soldiers were almost never able to prevent an attack or to mount a successful pursuit. The one officer who did show some aptitude for fighting the Apaches, Howard Cushing, was lured into a trap and killed in May 1871. Thus the situation in Arizona and New Mexico was as dire as that of Wyoming.

Ulysses S. Grant, who had been elected president in 1868 to succeed Andrew Johnson, had finally had enough. During his first years in office he had tried to follow Andrew Johnson’s peace policy toward the Indians. But the humiliation of the Indian attacks eventually impelled him to renounce the conciliatory approach in favor of renewed military action. The only questions now were about how to fight smarter, and who might be able to conduct a more effective campaign.

Grant reached out to an officer with considerable experience fighting Indians in the Pacific Northwest, both in the 1850s and again later in the 1860s, and whose combat record in the Civil War had been sterling: George Crook. In the years following the war, after having earlier subdued the Paiutes and pacified much of Idaho, Oregon, and northern California, Crook was sent to hold an administrative post in San Francisco. His job there was to determine which soldiers should be retained and which released from service during this period of overall force reductions. Grant knew there were better ways to use him and wanted to make him commander of federal forces in Arizona. Once that territory was tamed, Crook was to be placed in command in the northern plains. But William T. Sherman, who now headed the army, opposed the appointment on the grounds that Crook, a lieutenant colonel—he had temporarily held general officer rank during the war—was too junior. In this dispute the president asserted his authority as commander-in-chief, and Crook got the job.

Thus in the summer of 1871, beginning in Arizona, the government instituted a whole new approach to the conflict with the Indians: federal forces were to keep the tribesmen on the move. Instead of hunkering down in their forts or moving only in heavily armed convoys, U.S. troops would be called upon to move swiftly in small detachments, to master the terrain and the tactics of their enemies, to take the fight to them. Crook and his troops would have to accomplish this, if such a scheme were to work, against a host of highly skilled adversaries fighting with the indomitable will of those protecting their ancestral homelands. To defeat them would require the highest level of mastery of the art of irregular warfare.