Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (21 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

*

The man Grant chose to assume this challenge grew up a quiet Ohio farm boy whose father had volunteered him when the local congressman had asked whether one of his many sons might wish to go to West Point. George was put forward and accepted to the U.S. Military Academy, attending during the years immediately after the war with Mexico. He graduated in 1852, ranked thirty-eighth in a class of forty-three cadets, and was immediately sent off to the Pacific Coast—by ship to Nicaragua, overland to its west coast, then at sea again for the final leg of the journey. Crook’s initial duties were to keep the peace in northern California and southern Oregon. During this time he developed a great love of the wilderness and much respect for Native American peoples and cultures. Intellectual curiosity and his uncanny empathic ability to see the world through Indian eyes would serve him well.

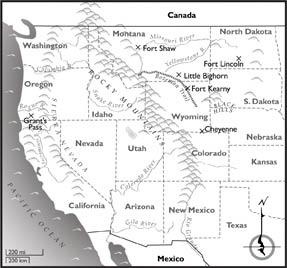

Theater of the Western Indian Wars

One of Crook’s closest friends during these years was John Bell Hood, who was to join the rebel cause in 1861 and would come to be known for conducting his battles with much dash but little subtlety during the Civil War. The two spent countless days hunting together. But where the wilderness soon gave Crook a great appreciation of stealth and swift raiding tactics, Hood was barely moved to question his basic notions of straightforward soldiering. Then and later, as Robert E. Lee once said of Hood, he was “all lion, none of the fox.”

3

Crook, on the other hand, very quickly showed his aptitude for bush fighting. This cleverness, along with his wise compassion, led the Native Americans to give him the sobriquet

NANTAN LUPAN

, the Gray Fox Chief. We shall see that he also had his share of the lion.

The first glimmers of Crook’s genius for irregular warfare came in the Rogue River War in Oregon in 1856. In this fight against elusive Indian foes, he realized that the fundamental dynamic in this kind of warfare was not the clash of mass on mass but rather the challenge of finding, then engaging the enemy before he could disappear once again. It is the same challenge that counterinsurgent leaders have faced from the French fight against Abd el-Kader in the 1830s–1840s to the American struggles against the Vietcong in the 1960s, and more recently against al Qaeda and its affiliates. The lesson Crook drew from Rogue River was the value to be found in subdividing one’s own force, however small it might be, so as to have many small units of maneuver hunting for the enemy rather than just one or a few big strike forces.

It was a concept of operations that worked well for Crook in the remote Far West, where he grew adept at swarming the Indians from several directions simultaneously. In a series of victorious fights he brought order to the region, albeit at the cost of an arrow in the hip whose head would stay in him the rest of his life. After Rogue River, Crook was sent farther north, taking his methods to the Columbia River basin and beyond, where he enjoyed similar successes. By 1859 he was back in southern Oregon and soon worked his way down again to San Francisco in preparation for a return trip east. He was in New York at the outset of the Civil War.

Given that the army was expanding rapidly, even a junior officer could hope to be given serious responsibilities from the start of the conflict. This was certainly the case with Crook, who was made a brevet colonel and placed in command of the Thirty-sixth Ohio Regiment, which was already deployed to West Virginia. In this area of operations the principal threat came from Confederate guerrilla fighters working in small bands, combining to mount raids and then dispersing afterward. Crook found the challenge they posed to be much like that of fighting the Indians, and his response was much as it had been on the Rogue River: break his command into a multitude of smaller units that kept themselves and, more important, the enemy on the move.

He had very good results with this approach. Rebel insurgents were kept on the run, often blundering into one of Crook’s flying columns. The tactics resulted in a lot of small-scale, vicious fighting at close quarters, instead of stand-up pitched battles. But they assured that the guerrillas were in no position to terrorize the people. And West Virginia stayed securely in the Union.

The only real problem Crook had during this period was with prisoners. When trapped by his flying columns, insurgents increasingly chose to surrender rather than fight. They knew they would likely be released on parole, which they would promptly violate. This infuriated Crook and his men, who sometimes found themselves capturing a guerrilla for the second or third time. Their brutal, unethical, but practical solution to the problem was to take no more prisoners. In his autobiography, Crook described the policy this way:

By this time every bushwhacker in the country was known, and when an officer returned from a scout he would report that they had caught so-and-so, but in bringing him in he slipped off a log while crossing a stream and broke his neck, or that he was killed by an accidental discharge of one of the men’s guns, and many like reports. But they never brought back any more prisoners.

4

Crook’s counterinsurgent methods in West Virginia—which have much in common with the kind of savagery often seen on both sides in other irregular wars, from the eighteenth century to our time—troubled some of his superiors. But his results impressed them, and he rose in rank and responsibility. By the summer of 1862 he was in command of a full brigade and was drawn deeply into more conventional fighting. He was soon chagrined to see his superiors’ seemingly unbounded faith in the efficacy of frontal assaults, despite the fact that they were usually hurled back with appalling loss of life.

Crook was particularly angered by events surrounding the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, a terrible, bloody day in American history when nearly twenty-five thousand soldiers from both sides combined were killed or wounded. Crook fought in the battle with great distinction that day, but could not conceal his disgust for Union generalship at the higher levels. He put his view of the senior commanders’ conduct in this battle quite bluntly: “Such imbecility and incompetency was simply criminal. . . . It was galling to have to serve under such people.”

5

Since Crook didn’t hold these thoughts for his memoirs but actually said them out loud, including to his superiors, he soon found himself transferred back to West Virginia. Later, by the summer of 1863, he was part of the campaign in the Western theater, where he was a brevet brigadier general in command of a division at the Battle of Chickamauga. Like his Confederate counterpart Nathan Bedford Forrest, Crook saw the brief opportunity the rebels had to exploit the opportunity gained in this battle. He noted: “If the enemy had followed up his victory vigorously, I don’t see how it would have been possible for the army to escape disaster.”

6

(Recall that Forrest broke with Bragg over this missed opportunity. From Crook’s point of view, the great rebel raider had every reason to do so.)

In 1864 Crook went east again at the request of Grant, who was taking command in the field there and of overall Union forces. Crook had caught Grant’s eye, and the chief wanted smart, hard-fighting generals under him. Soon Crook was in command of a cavalry corps operating in the Shenandoah Valley under General Philip Sheridan, whom he knew from West Point and had served with in the Pacific Northwest in the 1850s. At a key battle near Winchester, Virginia, Crook employed one of his surprise flanking maneuvers that totally unhinged the Confederate position, giving the day—and more than a thousand Confederate prisoners—to the Union. Sheridan took credit for crafting the maneuver in an official report, enraging Crook. So it went.

This would not be Crook’s last brush with self-aggrandizers. In another action, he came to the rescue of George Armstrong Custer, who had mounted an impetuous frontal assault on a strong rebel position. Custer was in dire straits, suffering heavy casualties, when Crook in his seemingly patented way struck the enemy from the flank, compelling them to capitulate. But it was Custer who then rode up to the enemy position himself, collecting Confederate battle flags as trophies to show his superiors. This episode and the one involving Sheridan led Crook to believe that it was “not what a person did, but it was what he got the credit for doing that gave him a reputation.”

7

Such comments hardly endeared him to his military colleagues and even bothered members of government whose ears his grumbling reached.

One night, two months before the end of the war in February 1865, a Confederate guerrilla team threaded its way behind the lines and was able to capture Crook and General Benjamin Kelley at their lodgings in Cumberland, Maryland, then make good its escape. The generals were brought to Richmond, where the rebel government sought to use them to enable a prisoner exchange on favorable terms. But Edwin Stanton, the Union secretary of war, indicated that he had no intention of bringing the troublemaker Crook back. Fortunately General Grant interceded, and Crook was returned. He was soon in action again, commanding in one of the final blocking battles that prevented Robert E. Lee’s escape from Grant’s grasp a few days before the surrender at Appomattox.

In the wake of the war Crook returned to the Pacific Northwest, after marrying in August 1865 at the age of thirty-six. Oddly, his wife Mary’s brother was one of the Confederate raiders who had captured him. The couple never had children and lived apart for long periods. Crook spent much of his time in the field during the last quarter century of his life while Mary remained at her family’s estate in Oakland, Maryland. For Crook it was to be seemingly endless years of long rides on muleback—he preferred mules to horses—and camp life, punctuated by bursts of intense combat. As good as he had become at fighting the various tribes of the Pacific Northwest he grew tired of his work in this region.

When President Grant asked him to turn around the disastrous situation in Arizona, Crook’s initial reaction was one of bare, grudging acceptance. But he soon realized that he would have a chance to learn about an entirely different Native American culture and would have the opportunity to test himself against irregular warriors who had confounded every single bluecoat general that had come up against them. For a thinking soldier like Crook, it was an opportunity not to be missed.

*

George Crook was something of a military mystic. A quiet man, he was given to long periods of study, reflection, and solitude. When he arrived in Arizona he camped outside the military installations he was visiting, hunted in the countryside, and spent the evenings making word lists of the Apache language. These were the things he had done to help him understand the terrain and the tribes of the Northwest, and he believed they would work in Arizona as well. He moved about with no retinue, was seldom in uniform—though he always carried a shotgun—and was once even mistaken for a common laborer and was offered a job as a mule-train packer. He politely turned down the opportunity and went his way. Like Nathan Bedford Forrest, Crook was abstemious. If he had a “brand,” it was rooted in his simple ways and contemplative silences.

After some weeks of orientation and meditation, Crook was ready to act. He realized that he needed to improve his forces in two areas in order to defeat Cochise, Geronimo, and the other Apache insurgents: mobility and scouting. To increase his troops’ speed of movement, he decided to operate without artillery, which he judged only slowed down a column and was of little use against enemies who refused to form up or fight from fixed positions. Crook also figured out how to strip down supplies to the bare minimum, so much so that his close colleague John Bourke said of him, “He made the study of pack-trains the study of his life.”

8

As to improving scouting, Crook realized that his bluecoats would never have sufficient ability to track the Apaches on their own, so he reached out to those who lived in and knew the country best. He first tried Mexican settlers who had learned to survive in Apache country, but they proved insufficiently aggressive in pursuit. At this point Crook had a great insight that Apaches could, and should, be used in the fight against other Apaches. He soon courted and won over the Coyotero and White Mountain tribes, who had long feuded with Cochise’s Chiricahuas, promising them that whites and Indians would work together to create a secure, peaceful land. It was the kind of message and method that would be used again by American troops in Iraq during 2006–2007, when many Sunni tribal insurgents were convinced, in the name of peace, to work against al Qaeda cadres.

Crook’s overture to the “enemy” generated a firestorm of criticism among white settlers in Arizona, who hewed more to the line of General Philip Sheridan that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.” Crook’s superiors in the military and the government were also skeptical. But Crook persisted and soon had a force of friendly Apaches able to track their foes speedily and unerringly. At first Crook simply wanted them to point out where the Chiricahua bands were, so that his now fast-moving bluecoats could engage them. But it proved difficult to hold his scouts back, so Crook let them start the fights as well—with excellent results. This teaming of outstanding native allies and better bluecoats, operating in hard-charging flying columns, soon brought the insurgent Apaches to heel. As to Crook’s insight into peeling off portions of the enemy populace to join the counterinsurgent cause, Martin Blumenson and James Stokesbury observed: “He was perhaps the first man in high places to recognize that the divisions separating groups of Indians could be used as a weapon.”

9