Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (17 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

In this manner Garibaldi kept Rome from capture for a month. During the siege, tensions between him and Mazzini erupted again when the latter refused Garibaldi’s heated requests to allow the defenders to break out and engage in guerrilla warfare against the French. Mazzini thought that by staying in Rome he would win more of the world’s sympathy. Perhaps so, but sympathy has seldom stopped a siege. Yet when Mazzini did decide to negotiate surrender terms, Garibaldi and those who wished to do so were authorized to break out. With Anita by his side—she had joined him just before the siege, leaving their children with his parents—and without Aguyar, who had been killed by an artillery shell, they and a small band rode out of Rome to the last cheers of the republic.

What followed was the most harrowing time in Garibaldi’s life, as he and Anita were chased across Italy with the loyalists. It was a time when, as Trevelyan wrote, “those who donned a red shirt . . . and faithfully wore it during the next month, deliberately chose a dress which, from one end of the Peninsula to the other, exposed the wearer to be hunted like a wolf and shot on sight.”

10

Anita, whose constitution had been worn down by the rigors of the siege, died during their flight. Garibaldi managed to escape with the help of members of the insurgent network throughout Italy, many of whom were found out by his pursuers and killed. Mazzini accepted exile to England. Once again he and Garibaldi were estranged. A decade later they were to join forces one more time, with far better results.

*

After almost a year on the run, Garibaldi landed in New York in the summer of 1850. He went there in part because Margaret Fuller, the proper Bostonian and friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau who had been in Rome during the siege—and had nursed wounded Republican fighters—had told him of the beauty of freedom in America. Fuller had also charmed Garibaldi with her assessment of the Roman republic as “the visionary country of her heart,” and he wanted to see the land from which such a wonderful woman came. Early on, however, all he saw was boiling tallow in the course of his work as a candle maker, the only job he could find.

Garibaldi worked the tallow for just under two years, then went back to sea for the next two, traveling first to Peru as a mate, then gaining a captaincy of his own for voyages to China, the Philippines, and finally, in 1854, to England. There he connected once more with Mazzini. Whatever their personal differences, Mazzini had been writing polemics about an Italian

RISORGIMENTO

(resurrection) that had caught the fancy of most of the world’s idealists. He had been particularly fulsome in his praise of Garibaldi, who was greeted in England as a great hero.

When they met, Mazzini convinced Garibaldi to return to Sardinia, simply to wait on events. Mazzini believed that French and Austrian interests would inevitably clash, providing yet one more opportunity for Italians to win their independence. Garibaldi was persuaded and made his way back. Charles Francis had abdicated some years before; his son Victor Emmanuel was made of sterner stuff. Indeed, he seemed quite the liberal and showed little concern about Garibaldi’s return. Perhaps this was because the great rebel settled on a farm on the small, rocky island of Caprera, off the coast of Sardinia.

For five years Garibaldi farmed. His children, who had been settled with cousins, stayed with him while he worked and waited. In 1859 the break came. Tensions between France and Austria reached a boil, and Victor Emmanuel contrived an alliance with Louis Napoleon, now Napoleon III, dictator of France. Their joining brought swift victory in the Battle of Solferino, the first in history in which both sides were armed almost entirely with rifles, the accurate infantry weapon that would change the face of nineteenth-century warfare.

11

For his part, Garibaldi had agreed, at the request of the king, to form an irregular corps, the Alpine Hunters, who performed skillfully.

In the wake of the war, the House of Savoy gained Lombardy from the Austrians, but at the price of giving Nice, Garibaldi’s birthplace, back to the French. Although troubled by this, Garibaldi agreed to serve as the king’s emissary to the people in several of the dukedoms that had been propped up by Austrian power. Garibaldi brought them all in. Central Italy was now unified, and greater gains were in the offing.

Garibaldi’s willingness to work with Victor Emmanuel in the name of the emerging Italian nation created yet another rift with Mazzini, one that never really healed. The aging revolutionary still could not stomach monarchy. But however this issue frayed their friendship, they remained in touch. And the next year Mazzini convinced Garibaldi that the time was ripe for a revolution against the Two Sicilies. Bomba’s son Francis now ruled every bit as harshly as his father had. The people yearned for a leader. Out of loyalty to Victor Emmanuel, Garibaldi discussed the matter with him and his chief diplomat, Count Cavour. Out of this meeting the notion arose of having Garibaldi travel to Sicily as a private citizen to help the suffering people there.

In May 1860 Garibaldi and other concerned citizens—about a thousand, indeed they would come to be known as “the Thousand”—landed on the west coast of Sicily at Marsala. They were greeted with great enthusiasm, but few Sicilians actually joined their ranks. The Thousand, more than a hundred of them medical students, were lightly armed and vastly outnumbered by Francis’s forces, and now had to plan their offensive in the absence of a massive popular uprising. Their first battle came at Calatafimi, where the king’s forces, more than two thousand, were dug in on a terraced hill. Garibaldi broke his force into a number of small units and assaulted the summit from every angle, taking advantage of the slight cover offered by each terrace. After a hard fight, Francis’s men were routed, and Garibaldi began his march on Palermo.

Because the numbers he would soon face were in the tens of thousands, Garibaldi resorted to some of the tactics he had employed as a guerrilla fighter in South America. He feigned a retreat with elements of his force while most of his men closed in on Palermo. The enemy was duped, sending almost five thousand troops on a chase into central Sicily. Still, a garrison of more than sixteen thousand remained in Palermo, backed up by warships that could provide fire support. Despite these odds, Garibaldi drove on into the city with perhaps seven hundred of his original Thousand and a slightly larger number of Sicilians who had joined the cause after Calatafimi.

Here at Palermo Garibaldi would enjoy both a tactical and a strategic victory. Once inside the city, he dispersed his Thousand in small bands, attacking the enemy everywhere simultaneously. The far larger defending force fell back on the city center and port, the warships indiscriminately bombarding the parts of the city that had been occupied. Still Garibaldi pressed on, pioneering the mode of operations that the great Chechen fighter Aslan Maskhadov would employ against the Russian army in Grozny in 1996, when he drove them out against similar odds. But where Maskhadov gained momentum against the Russians as the struggle wore on, Garibaldi’s force was coming apart. They had little ammunition, so most of the raids featured hand-to-hand combat. Losses were high, and the Thousand were dwindling dangerously low in number.

At this moment Garibaldi struck a psychological blow: he offered a ceasefire and an opportunity to discuss terms of withdrawal for the king’s men. They accepted. And left. Soon Garibaldi overran the rest of Sicily with lightning raids, landing thereafter at Melito on the toe of Italy’s boot. From there he began his campaign against Naples, the king’s great stronghold. Francis panicked and fled, leaving the city to Garibaldi, who arrived there in September 1860.

Mazzini had also come to Naples, to give Garibaldi the green, white, and red flag that had flown over the Roman republic during its short life. When they met, Garibaldi told him that the flag would also be adorned with the coat of arms of the House of Savoy. Mazzini expected this but was nonetheless crushed, as he had held out hope to the last that Garibaldi would turn antimonarchist. He parted from Garibaldi and left for England. Mazzini spent the last twelve years of his life in self-exile from the Italy whose modern emergence he had done so much to bring about.

After Mazzini’s departure, Garibaldi finally met in direct battle against Francis, who had cobbled together a new army and tried to march on Naples. Garibaldi beat him in a pitched battle at the Volturno River, and the threat was ended. Victor Emmanuel had been campaigning at the same time in central Italy, freeing the papal states. He entered Naples as the first king of Italy on November 7, 1860, making it clear that he was to be the constitutional monarch of a democratic nation.

Soon after Victor Emmanuel’s entry into Naples, Garibaldi sailed for his farm on Caprera with a bag of seed corn, all he took for his labors.

12

He lived there with his children, remarried and had two more children in his old age. Occasionally the trumpets sounded a call to arms. During the American Civil War, when Union prospects were at their lowest, an aide to President Lincoln made an overture to Garibaldi to come help. Nothing came of it as both the government in Washington and Garibaldi had second thoughts.

13

At about the same time he launched an ill-advised campaign against the last papal holding, Rome itself. This “Aspromonte Affair” ended badly, with Victor Emmanuel’s troops stopping the march, and wounding Garibaldi in the process.

But there was no deep rift with the king. In 1866 Victor Emmanuel asked Garibaldi to command an irregular force once more against the Austrians, which he did with distinction. The following year he led another disastrous, unauthorized march on Rome, this time losing about a thousand of his followers in battle with the French forces still protecting the city Louis Napoleon had so brutally taken from the republic nearly twenty years earlier.

Garibaldi’s last foray into the field came in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, when he joined the side of the French republic that was declared in the wake of Napoleon III’s abdication. Victor Emmanuel took the opportunity to seize Rome for Italy, but Garibaldi, now sixty-three, led a force of irregulars drawn from many nations to fight the Prussians in France. Of his last battles in the Vosges Mountains, his opposite number, General Edwin von Manteuffel said of Garibaldi that he admired “the great speed of his movements” and his “energy and intensity in attack.”

14

The old lion still had some fight in him, it turned out, and the novelist Victor Hugo went so far as to claim that Garibaldi was the only general on the French side that the Prussians had not beaten.

But the Vosges campaign was his last lightning. Garibaldi returned to Caprera after the war and spent the last decade of his life on the farm he had come to love. He enjoyed being known as the “man of the age” but seldom left the island. His life grew ever simpler; after he finished his memoirs there was little left to do in explaining the course and purpose of his life to his fellow Italians and to the world.

The only item that remained tantalizingly out of reach was Garibaldi’s philosophy of irregular warfare. Where Mazzini had mounted something of an offensive of platitudes and generalizations in his treatise on guerrilla operations, Garibaldi remained mostly mute about the idea of there being principles of irregular warfare. Perhaps this is because his great campaigns already speak so eloquently about the power of the few, when properly employed. Even in defeat, as in Rio Grande do Sul and in Rome, Garibaldi’s small, swarming detachments and relentless pursuit of the offensive achieved remarkable results. But it is in his victories, on the defensive in Montevideo and in the amazing city fight for Palermo, that Garibaldi left us monuments to the art of irregular warfare that should stand as long as soldiers have memories.

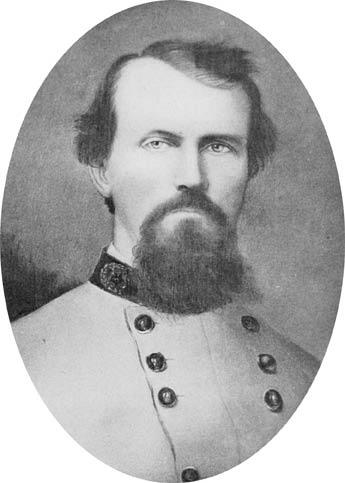

REBEL RAIDER:

NATHAN BEDFORD FORREST

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Brady-Handy Photograph Collection

Just months after Garibaldi’s great triumphs in Sicily and Naples, which did so much for Italian nationhood, the American Civil War broke out. It grew from a long-simmering dispute over the appropriate extent of central government, and from a deep-seated belief on the part of many Americans that the constitutional right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness required an end to the enslavement of African Americans. It is interesting that both sides in these disputes looked to Garibaldi for inspiration. As Derek Leebaert has observed, he was “a nation-builder to Federals (with New York’s ‘Garibaldi Guards’), who saw themselves preserving a country, and to Confederates, who were confident that they were bringing one to birth.”

1

Thus nationalism once again sparked conflict. On this occasion, however, the scale was to dwarf the size of most other nationalist wars—save for those of the Napoleonic Era—and it would be the first truly modern war. That is, during all its four years the Civil War was waged with mass-produced rifles and artillery, and troops regularly moved by rail, with their actions coordinated by telegraph.