Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (15 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

This was indeed his best chance, and in 1845 the Bou Maza movement did arise—something that looked a lot like what we would call a network today, and which John Kiser has labeled a “hydra.”

12

Soon the number of insurgent attacks began to rise again, and Bugeaud’s greatest concern was probably that French war weariness would set in. This fear may have led him not only to tolerate but also to endorse some of the worst atrocities of the war in the hope that the Algerians would be terrorized into giving up the fight.

Thus in June 1845 one of his subordinates, a Colonel Pelissier, personally set a fire at the mouth of a cave where more than five hundred men, women and children were sheltering. All but ten of them were asphyxiated. Pelissier claimed to be proud of his action. In August a Colonel Saint-Arnaud, eschewing fire, instead chose to entomb three times that number of insurgents in another cave. Showing that he had some sense of the evil he had done and the outrage that wide knowledge of the atrocity would spark, Saint-Arnaud sent a private message to assure Bugeaud that all was done in secret: “No one went into the cave. Not a soul but myself.”

13

But word did get out, and soon the world came to call Bugeaud the “Butcher of the Bedouins.”

Yet these French actions were for naught. The atrocities may have terrorized some into submission, but they galvanized others to action. Abd el-Kader himself soon showed his fangs again too. In September 1845 he ambushed a French flying column of more than four hundred cavalry. Only seventeen avoided death or capture. The insurgent leader then went after a supply convoy, taking its goods and more than two hundred prisoners. In response, Bugeaud unleashed eighteen flying columns simultaneously, the goal being to flush out and track down Abd el-Kader. They failed to do so. Bugeaud authorized more atrocities, as well. But the French government and people finally grew sufficiently outraged to relieve Bugeaud of his command in June 1847. He was replaced by Louis-Christophe-Léon Juchault de Lamoricière, an officer who had served in Algeria since 1830, rising from captain to general.

Lamoricière was about the same age as Abd el-Kader and shared his deep interest in theological matters. He had been appalled by French excesses and, soon after taking command, put out peace feelers. Abd el-Kader, who respected his opponent’s skills honed over many years in the field, accepted the offer to negotiate peace one more time. He even agreed to surrender if it would bring an end to the suffering and allow his fellow Algerians to live in decent conditions under French rule.

In December 1847, Abd el-Kader went willingly into captivity in France. His stay there was supposed to be brief, as King Louis-Philippe had promised him a comfortable exile in Alexandria. But the king abdicated in February 1848, in the wake of a social revolution, and Abd el-Kader was held in custody. It would take much lobbying by many of his former adversaries—including his bitter foe Saint-Arnaud, now minister of war for the new government of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew of the great conqueror—to obtain his release. But by December 1855 he was living in exile in Damascus.

During this last phase of his life Abd el-Kader returned to the religious meditations that had so interested him as the son of a Muslim holy man. He also entertained visitors and made friends among those from the West who admired his life and accomplishments, notably the British explorer/adventurer Richard Francis Burton. His only return to “action” came in the summer of 1860 when anti-Christian riots in Damascus saw hundreds of Europeans being massacred. Abd el-Kader rescued many, giving them sanctuary in his compound and standing up against the raging mob, trying to calm and disperse them. He saved thousands of lives.

In the following years Abd el-Kader resumed his life of quiet contemplation, shared his thoughts with others, and reflected ever more deeply on the common values that lay at the heart of all major faiths. But the world did not forget his accomplishments in the field. When he died on May 25, 1883, the obituary in the

NEW YORK TIMES

called him “one of the ablest rulers and most brilliant captains of the century.” Algeria would remain under French rule for another eighty years but the next time brutal methods were used to try to defeat insurgents there, the French people would be so appalled by their own military’s behavior that Algeria was finally set free. As Abd el-Kader always believed it would be.

NATION BUILDER:

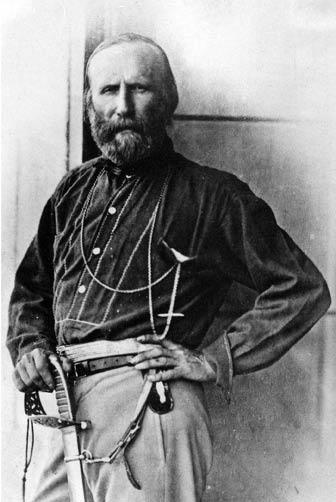

GIUSEPPE GARIBALDI

Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884), Portrait de Giuseppe Garibaldi (1808–1882) à Palermo en 1860

Perhaps the most powerful force unleashed upon the world by the French Revolution was the notion of nationalism. The millions who were mobilized to fight for France did so largely out of a sense of commitment to country. And those who resisted Napoleonic invasion and occupation, especially in Spain, Prussia, and Russia, were imbued with much the same spirit. Certainly the idea of nationhood also inspired a measure of the resistance to colonial control that energized so many of the peoples that the great powers sought to bring under their influence during the nineteenth century. Most of these resisters fought heroically in the names of their actual or hoped for national identities, like the Poles who were crushed by Davydov, and the Algerian tribes led by Abd el-Kader. Yet almost all of them failed to stem the rising tide of imperialism—which would not ebb until the aftermath of World War II, when the empires had either been toppled or were exhausted, and a series of successful “people’s wars” arose around the world to throw off their rule.

Before then, however, there were few points of light. Empires dominated nations so greatly that by 1900, as Lenin observed, more than 90 percent of the land mass of Africa (up from just 10 percent in 1876) nearly 60 percent of Asia, and 99 percent of Polynesia had been subjugated by imperial powers.

1

South America was to some degree insulated from colonialism by the Monroe Doctrine, but the more localized empires that were forming there sought to crush nascent nations—like Uruguay and the various republics trying to break free from Brazil—whenever they could. Only a few places successfully resisted imperialism. In Asia, Siam would remain free, as would Ethiopia in Africa—the latter at least until the 1935 Italian invasion.

In Europe perhaps the greatest exception to imperial control arose in Italy, a land over parts of which France, Spain, and Austria had been fighting for hundreds of years. From the sixteenth-century Italian Wars during Machiavelli’s time—the cynical master of realpolitik actually concluded

THE PRINCE

with an idealistic exhortation to free Italy from foreign rule—to the post-Napoleonic hodgepodge of spheres of influence that ran from the Alps to Sicily, here were lands and peoples that had not been truly unified since the fall of the Roman Empire.

In the decades after the fall of Napoleon, unification in Italy seemed little short of impossible. Direct Austrian control in the north was only partially offset by more subtle French influence, under their restored monarchy, in other parts of Italy, including Piedmont and the papal territories around Rome. While Spain had long left the great game for Italy behind, France and Austria more than made up for this absence by vying for influence with the many independent principalities and dukedoms that had emerged over time. In sum, Italy seemed one of the least likely places in the world where nationalism might triumph over well-heeled, highly motivated imperialism.

Even in the unlikely event that the great powers could be driven out militarily, local rulers—like the House of Savoy in Piedmont, the pope in Rome, or the proud Venetians—would strongly resist ceding their power to a new national authority. Yet none of these obstacles deterred a whole generation of grassroots resisters—drawn from peasant farmers, fishermen, and students—from coming together in the Young Italy organization and fighting for their imagined country.

The roots of this resistance lay in yet another organization, a more secret one known as the

CARBONARI

. The name was chosen to make a symbolic connection with carbon as it is found in coal—a hard substance that is slow to ignite but is a great source of energy. This secret society was organized along very networked lines, with small cells and nodes communicating for the most part in the Austrian-occupied parts of northern Italy—though the original aim of the group was to push out the French. The basic strategy for liberation was to foment unrest in the hope of provoking France and Austria into fighting each other, with Italians seizing the opportunity to escape their grasp and declare independence.

What followed, then, were simultaneous small uprisings in 1830 and 1831, during which the

CARBONARI

found that the Austrians knew how to network as well. Insurgent cells throughout Italy soon found they had been infiltrated, and many of their members were killed or captured. Austrian secret police even followed the links between group members into France, where their “hit squads” kidnapped or assassinated many more. Indeed, the whole Austrian campaign against the

CARBONARI

offers a textbook-like example of how to take apart a network by means that might be described as infiltration followed by exploitation.

Out of the ashes of the

CARBONARI

, survivors fled to several other European countries, and many made their way to South America as well. One of the most important refugees was Giuseppe Mazzini, a lawyer, writer, and revolutionary who became the principal architect of the new, reshaped resistance to be mounted by Young Italy. He realized that the great powers could not easily be played off against one another to Italy’s benefit. Instead he called in his manifesto for the organization to focus single-mindedly on waging an “insurrection by guerrilla bands.”

2

Mazzini’s call to arms was enthusiastically greeted, and soon the ranks of resisters were swelling once again, not only in Italy, for nationalists in several other countries were drawn to the notion of mounting armed resistance against the ruling empires of the Concert of Europe. It made the early 1830s a tense time. The wrath of the masses had been truly kindled, and now they had received a practical guide to action from Mazzini. The defenders of the existing order felt so threatened that one of their leaders, Prince Metternich of Austria—the Henry Kissinger of his time—went so far as to decry Mazzini as “the most dangerous man in Europe.”

3

Metternich may have been right conceptually, but in practical terms Mazzini, the gaunt intellectual, was badly miscast for the role as a man of action who could lead his movement to victory in the field. Even his strategic vision was limited, and it would be left to others to flesh out the general notion of

GUERRA ALLA SPICCIOLATA

(war little by little) that Mazzini had in mind. While there was no lack of good ideas among Italians about how to wage irregular warfare—particularly as articulated by the school of thought led by Carlo Bianco, Guglielmo Pepe, and Cesare Balbo—there was yet no “man on horseback” to lead them to victory in battle. Instead their and Mazzini’s particular contributions were conceptual. As Walter Laqueur has put it, they were the first to make “the link between guerrilla warfare and radical politics”

4

that would inspire so many people’s wars over the next 150 years.

Initially Mazzini thought that such an inspirational leader might not be necessary; but the savage defeats suffered in 1830–1831 had made him more sensitive to the need for a charismatic commander. And so he began to look for leadership potential among his recruits. In a back-alley lodging in Marseilles, at a secret meeting of Young Italy there in 1833, Mazzini met a new fellow who had come to the cause, Giuseppe Garibaldi. Already at this first meeting, Mazzini speculated that this bluff merchant sea captain might have the qualities he was looking for. Physically imposing, Garibaldi was also inspiring in his comments about how Italians would drive out their occupiers. Other Young Italy cell members at the meeting were equally impressed with Garibaldi’s potential as a man of action. His biographer Nina Baker characterized the meeting this way: “Mazzini, the Head, and Garibaldi, the Arm, had come together, and the revolution had begun its thunderous course down the corridors of history.”

5

Perhaps so, but the thunder would roll for a very long time before the storm broke in its full power.

*

Only two years younger than Mazzini, Giuseppe Garibaldi was born in 1807 in Nice, which had been the Italian Nizza until French annexation by conquest in 1792. It was returned to the House of Savoy after Napoleon’s abdication in 1814. Garibaldi’s father was a fisherman, and the son soon followed the father’s path to the sea, learning his trade as a merchant seaman on voyages throughout the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. He first learned of Mazzini from a fellow trader, and Italian nationalist, whom he met when both were in the Crimea on business. The meeting between Garibaldi and Mazzini that soon followed in Marseilles sparked a close relationship between the two that was sometimes roughened by serious conflicts over strategy; but neither ever questioned the other’s commitment to their noble cause.