Inventing the Enemy: Essays (31 page)

Read Inventing the Enemy: Essays Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

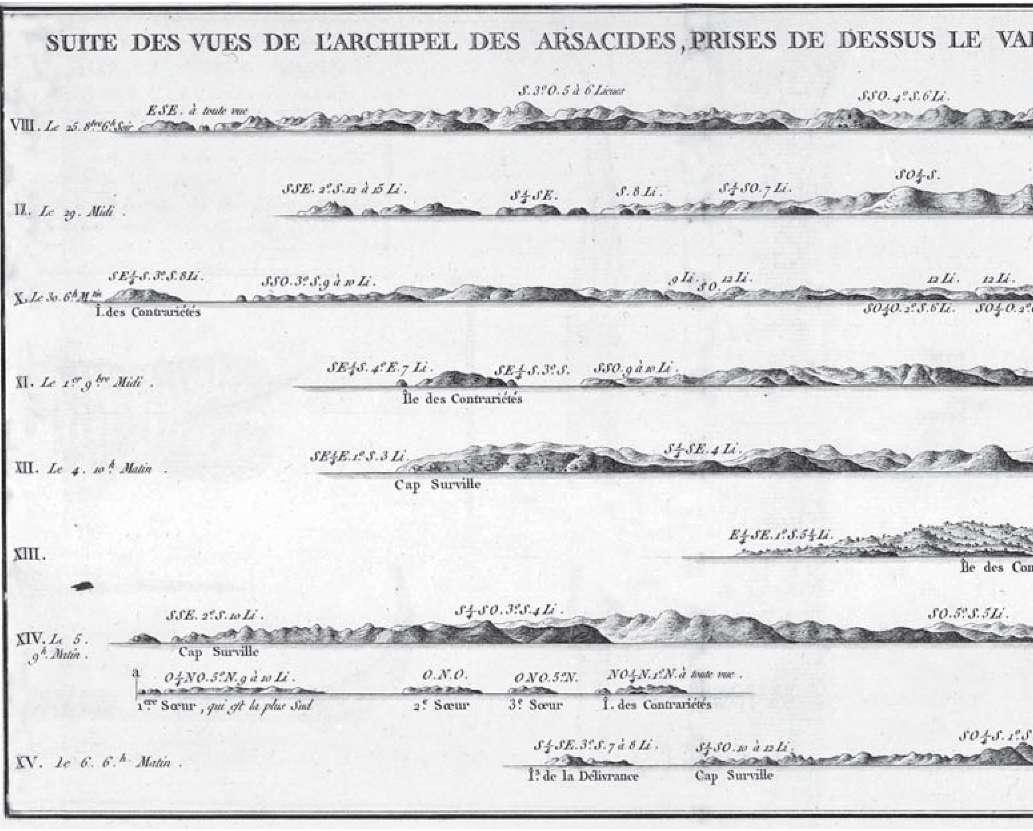

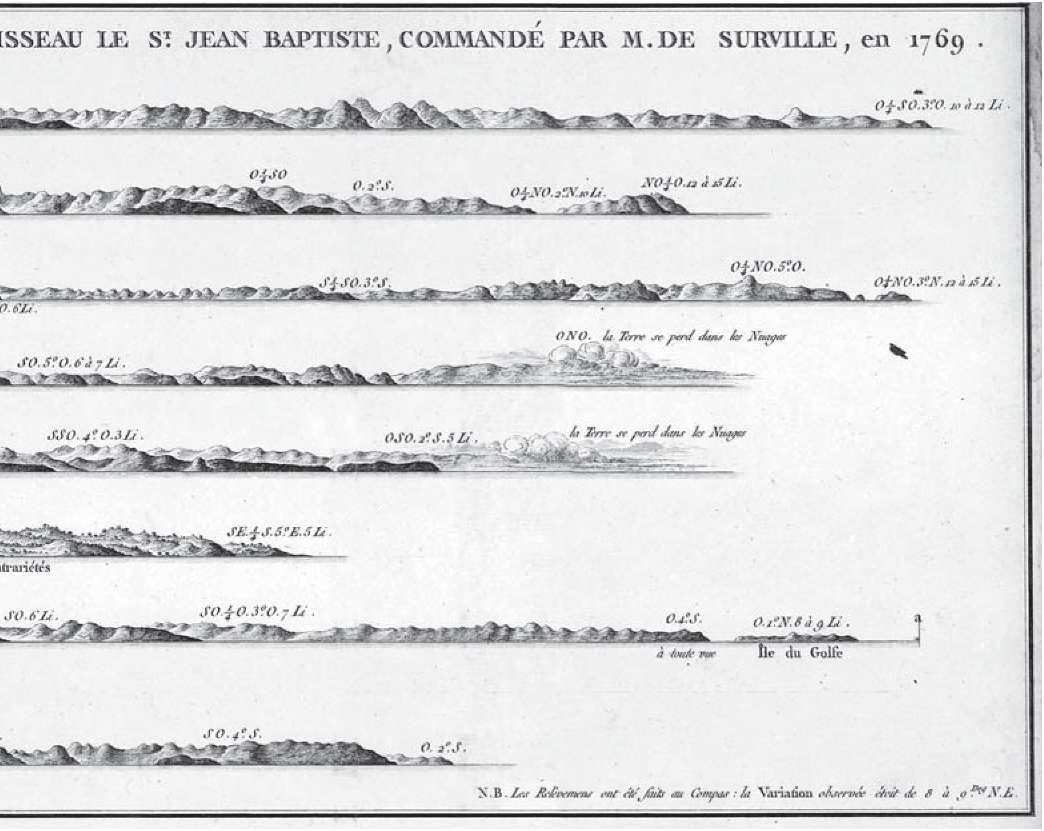

I don’t suppose Gozzano had in mind some of the maps we find in eighteenth-century books on sea travel, but this idea of the island that “fades away, like a vain shadow, tinged with the azure color of faraway” makes us think about the way in which, before the problem of longitude had been solved, islands were identified using drawings of their profiles as they had been seen for the first time. Arriving from a distance, the island (whose shape did not exist on any map) was recognized from its

skyline,

as we would say of an American city today. And what happened if there were two islands with very similar skylines, as if there were two cities, both with the Empire State Building and (at one time) the Twin Towers south of it? They would land on the wrong island, and who knows how many times this happened.

Moreover, the profile of an island changes with the color of the sky, the haze, the time of day, and perhaps even the time of year, which alters the appearance of the vegetation. Sometimes the island is tinged with the azure color of faraway, it can disappear in the night or in the mist, or clouds can hide the shapes of its mountains. There is nothing more elusive than an island about which we know only its profile. Arriving on an island for which we have neither map nor coordinates is similar to moving about like one of Edwin Abbott’s characters in Flatland, where there is only one dimension and we see things only from the front, like lines with no thickness—with no height and no depth—and only someone from outside Flatland could see them from above.

And it was said, in fact, that the inhabitants of the islands of Madeira, La Palma, La Gomera, and El Hierro, deceived by the clouds or by the mirages of the fata morgana, sometimes thought they had seen the

insula perdita

toward the west, shimmering between the water and the sky.

Thus, in the same way that an island that didn’t exist could be sighted among the reflections of the sea, so it was also possible to confuse two islands that

did

exist, or never to find the one that was the intended destination.

And that is how islands become lost.

And why islands are never found. As Pliny said (book 2, chapter 96), some islands are forever wavering.

[Published in the

Almanacco del bibliofilo—Sulle orme di san Brandano

(Milan: Rovello, 2011) and based on a paper given at a conference on islands held in Carloforte, Sardinia, in 2010.]

I

N TERMS OF CONTENT

, WikiLeaks has turned out to be a false scandal, but in terms of its formal implications, it has been, and will prove to be, something more. As we shall explain, it marks the beginning of a new chapter in history.

A false scandal is one in which something becomes public that everyone had known, and had been talking about in private, and that, so to speak, was only being whispered about out of hypocrisy (for example, gossip about adultery). Everyone knows perfectly well—not just those well-informed about diplomatic matters but anyone who has ever seen a film about international intrigues—that embassies have lost their diplomatic role since at least the end of the Second World War, in other words since the time when heads of state could pick up the telephone or fly off to meet each other for dinner (was an ambassador sent off in a felucca to declare war on Saddam Hussein?). Except for minor tasks of representation, they have been transformed, more overtly, into centers to gather information on the host country (with more competent ambassadors playing the role of sociologist or political commentator) and, more covertly, into full-blown dens of espionage.

But now that this has been openly declared, American diplomacy has had to admit that it is true, and therefore to suffer a loss of image in formal terms—with the curious consequence that this loss, leak, flow of confidential information, rather than harming the supposed victims (Berlusconi, Sarkozy, Gaddafi, or Merkel), has harmed the supposed perpetrator, in other words, poor Mrs. Clinton, who was probably just receiving messages sent by embassy staff carrying out their official duties, as this was all they were being paid to do. This, from all the evidence, is exactly what Assange wanted, since his grudge is against the American government and not against Berlusconi’s government.

Why have the victims not been affected, except perhaps superficially? Because, as everyone realizes, the famous secret messages were simply “press echo,” and did no more than report what everyone in Europe already knew and was talking about, which had even appeared in America in

Newsweek.

The secret reports were therefore like the clippings files sent by company press offices to their managing director, who is too busy to read the newspapers.

It is clear that the reports sent to Mrs. Clinton are not about secret dealings—they were not spy messages. And although they dealt with apparently highly confidential information, such as the fact that Berlusconi has private interests in Russian gas deals, even here (whether true or false) the messages would have done no more than repeat what had already been talked about by those who in Fascist times were branded café strategists, in other words, those who talked politics at the bar.

And this goes to confirm another well-known fact, that every dossier compiled for the secret service (in whatever country) consists entirely of material already in the public domain. The “extraordinary” American revelations about Berlusconi’s wild nights reported what could have been read months earlier in any Italian newspaper (except the two controlled by the premier), and Gaddafi’s satrapic follies had for some time been providing—rather stale—material for cartoonists.

The rule that secret files must contain only information already known is essential for the operation of a secret service, and not just in this century. Likewise, if you go to a bookshop specializing in esoteric publications, you will see that every new book (on the Holy Grail, the mystery of Rennes-le-Château, the Knights Templar, or the Rosicrucians) repeats exactly what was written in earlier books. This is not simply because occult writers are averse to carrying out new research (nor because they don’t know where to go looking for information about the nonexistent), but because followers of the occult believe in only what they already know, and in those things that confirm what they have already learned. It is the formula behind the success of Dan Brown.

The same happens with secret files. The informant is lazy, and the head of the secret service is either lazy or blinkered—he only regards as true what he already recognizes.

Given that the secret services, in any country, aren’t able to foresee events like the attack on the Twin Towers (in some cases, being regularly led astray, they actually bring them about) and that they file only what is already known, it would be just as well to be rid of them. But in present times, cutting more jobs would indeed be foolish.

I have suggested, however, that while in terms of its contents it was a false scandal, in terms of its formal implications, WikiLeaks has opened a new chapter in history.

No government in the world will be able to maintain areas of secrecy if it continues to entrust its secret communications and its archives to the Internet or other forms of electronic memory, and by this I mean not only the United States but even San Marino or the Principality of Monaco (and perhaps only Andorra will be spared).

Let us try to understand the implications of this phenomenon. Once upon a time, in Orwell’s day, Power could be seen as a Big Brother who monitored every action of every one of its subjects, particularly when no one was aware of it. The television Big Brother is a poor caricature because everyone can follow what is happening to a small group of exhibitionists, assembled for the very purpose of being seen—and therefore the whole thing is of purely dramatic and psychiatric relevance. But what was just a prophecy in Orwell’s time has now actually come true, since the Power can follow people’s every movement through their mobile telephones, through every transaction, hotel visit, and motorway journey carried out using their credit card, through every supermarket visit followed on closed-circuit television, and so on, so that the citizen has fallen victim to the eye of a vast Big Brother.

That, at least, is what we thought until yesterday. But now it has been shown that not even the Power’s innermost secrets can escape a hacker’s monitoring, and therefore the relationship of monitoring ceases to be one-directional and becomes circular. The Power spies on every citizen, but every citizen, or at least the hacker appointed as avenger of the citizen, can find out all the secrets of the Power.

And even though the vast majority of citizens are unable to examine and evaluate the quantity of material that the hacker seizes and makes public, a new rule of journalism is taking shape and is being put into practice at this very moment. Rather than recording the important news—and once upon a time it was governments who decided what items were really important, whether it was declaring war, devaluing a currency, signing a treaty—the press now decides independently what news ought to be important and what news can be kept quiet, even negotiating with the political power (as has happened) over which disclosed “secrets” to reveal and which to keep quiet.

(Incidentally, given that all secret reports fomenting government hatred or friendship originate from published articles, or from confidential information given by journalists to embassy officials, the press is coming to assume another purpose—at one time it spied on foreign embassies to find out about secret plots, but now it is the embassies that are spying on the press to find out about events in the public domain. But let us get back to the point.)

How can a Power hold out in the future, when it can no longer keep its own secrets? It is true, as Georg Simmel once said, that every real secret is an empty secret (because an empty secret can never be revealed) and holding an empty secret represents the height of power; it is also true that to know everything about the character of Berlusconi or Merkel is in fact an empty secret, so far as secrets are concerned, because it is material in the public domain. But to reveal that Hillary Clinton’s secrets were empty secrets, as WikiLeaks has done, means removing all power from the Power.

It is clear that countries in the future will no longer be able to hold secret information online—it would be just the same as posting it on a street corner. But it is equally clear that with current surveillance technology there is no point in hoping to carry out confidential transactions by telephone. And nothing is easier, moreover, than to find out where and when a head of state has flown off to meet a colleague . . . not to mention those popular jamborees for demonstrators that are the G8 meetings.

How then can private and confidential relationships be carried on in future? What reaction might there be to the irresistible triumph of Complete Openness?

I am well aware that for the time being my prediction is science fiction and therefore fanciful, but I cannot help imagining government agents riding discreetly in stagecoaches or calèches along untrackable routes, along the country roads of more desolate areas—and those not blighted by tourism (because tourists use their mobile phones to photograph anything that moves in front of them)—carrying only messages committed to memory or, at most, hiding a few essential pieces of written information in the heel of a shoe.

It is most appealing to imagine envoys from the Glubbdubdrib Embassy meeting the messenger from Lilliput on a lonely street corner, at midnight, murmuring passwords in their brief furtive encounter. Or a pallid Pierrot, during a masked ball at the Ruritanian court, who draws back from time to time to where the candles have left an area of shadow, and takes off his mask, revealing the face of Obama to the Shulamite who, swiftly drawing aside her veil, we discover to be Angela Merkel. And there, between a waltz and polka, the meeting will at last take place, unbeknownst even to Assange, to decide the fate of the euro, or the dollar, or both.

All right, let us be serious. It won’t happen like that. But in some way or other, something very similar will have to happen. In any event, information, the recording of a secret interview, will then be kept as a single copy or manuscript, in a locked drawer. Just think: ultimately, the attempted espionage at the Watergate Complex (which involved forcing open a cupboard and a filing cabinet) was less successful than WikiLeaks. And I recommend this advertisement to Mrs. Clinton. I found it online: