Inventing the Enemy: Essays (28 page)

Read Inventing the Enemy: Essays Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

U

TOPIAS ARE FOUND

on islands (with a few rare exceptions, such as the realm of Prester John). The island is thought of as inaccessible, a non-place where you land by chance, and once you have left, you can never return. So only on an island can a perfect civilization be created, and we discover it only through legends.

The Greek civilization lived on archipelagos and ought to have been quite used to islands, yet it is only on mysterious islands that Ulysses meets Circe, Polyphemus, and Nausicaa. There are those islands we read about in Apollonius of Rhodes’s

Argonautica;

there are the Blessed or Fortunate Islands where Saint Brendan lands during his voyage; Thomas More’s city of Utopia is on an island, and there are those perfect, thriving unknown civilizations dreamed about in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, such as Foigny’s Terra Australis and Vairasse’s island of Sevarambes. The mutineers from the

Bounty

search for the lost paradise on an island (without finding it); Verne’s Captain Nemo lives on an island; both Stevenson’s and the Count of Monte Cristo’s treasures lie hidden on an island, and so on until we reach the dystopias, from the island of Doctor Moreau’s Beast Folk to the island of Doctor No, where James Bond lands.

What is the fascination of islands? It is not so much that they are places cut off from the rest of the world. Marco Polo or Giovanni Pian del Carpine found places far away from human society by crossing endless tracts of terra firma

.

Until the eighteenth century, when it became possible to calculate longitude, mariners would come across an island merely by chance, and, like Ulysses, would escape from it, but there was no way of finding their way back there. From the time of Saint Brendan (and even up to Gozzano) an island was always an

insula perdita,

a lost island.

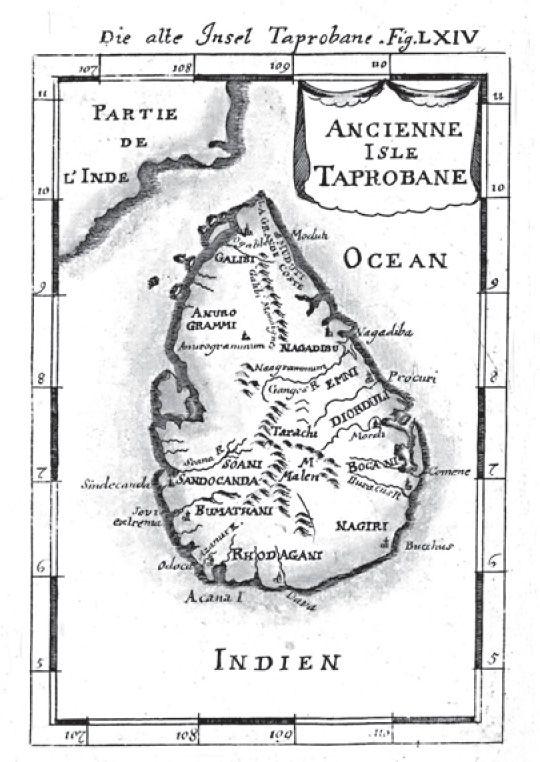

This explains the success and fascination of that highly popular genre of island stories in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which provide a record of all the islands in the world—known islands as well as those about which there were just a few vague legends. The island stories, in their own way, provided as much geographical accuracy as possible (unlike the tales of fabulous lands in earlier centuries) and were a blend of folk tales and traveler’s accounts. Sometimes they were wrong. It was thought, for example, that there were two islands, Taprobane and Ceylon, whereas in fact (as we know) there was just one—but so what? They represented a geography of the unknown or, at least, the little-known.

Later came the journals of the eighteenth-century travelers—Cook, Bougainville, La Pérouse . . . They too were looking for islands but were careful to describe only what they saw, no longer relying on folk traditions—and that was quite a different matter. But still they went off looking for islands that didn’t exist, such as Terra Australis (which appeared on all atlases), or for an island that someone had once discovered but had never been found again.

This is why, still today, our fantasies drift between the myth of

an island that doesn’t exist,

or the myth of absence; that of

one island too many,

or the myth of excess; that of

the undiscovered island,

or the myth of inaccuracy; or that of

the un-rediscovered island,

or the myth of the

insula perdita,

the lost island—four quite different stories.

The first is a legendary story. Legends about islands are generally divided into those that require us to pretend the island exists (asking us to suspend our belief)—as with the islands of Verne or Stevenson—and those that describe an island that does not exist by definition and have the sole purpose of reaffirming the power of legends—as with Peter Pan’s Neverland. The island that, by definition, does not exist is of no interest to us, at least today. The reason is simple: no one goes looking for it—children don’t go to sea looking for Captain Hook’s island, nor do adults go in search of Captain Nemo’s island.

Likewise, I will pass over the

one island too many,

not least because there is, I believe, only one case of this phenomenon of excess—the duplication of Ceylon and Taprobane. This story has been told in much detail in an article on island stories by Tarcisio Lancioni

1

to which I refer you. In fact, what interests me today is that unfortunate love for an island that can no longer be found, whereas Taprobane was always being found, even when no one was looking for it, and therefore, in terms of sexual exploits, we might say it was not so much a story of hopeless passion as one of Don Giovanni–like incontinence, where the number of maps showing Taprobane had already reached

mille e tre.

According to Pliny, Taprobane was discovered during the time of Alexander the Great, and prior to that had been generally indicated as the land of the Antichthones and considered “another world.” Pliny’s island could be identified as Ceylon, and this can be seen from Ptolemy’s maps, at least in the sixteenth-century editions. Isidore of Seville also places it to the south of India and confines himself to saying that it is full of precious stones and has two summers and two winters each year. Marco Polo’s

Travels

doesn’t give the name Taprobane but refers to Ceylon as Seilam.

The duplication of Ceylon and Taprobane appears quite clearly in Mandeville’s

Travels,

which describes them in two different chapters. He doesn’t say exactly where Ceylon is located but states that it is “well a 800 miles about” and is

full of serpents, of dragons and of cockodrills, that no man dare dwell there. These cockodrills be serpents, yellow and rayed above, and have four feet and short thighs, and great nails as claws or talons. And there be some that have five fathoms in length, and some of six and of eight and of ten. And when they go by places that be gravelly, it seemeth as though men had drawn a great tree through the gravelly place. And there be also many wild beasts, and namely of elephants. In that isle is a great mountain. And in mid place of the mount is a great lake in a full fair plain; and there is great plenty of water. And they of the country say, that Adam and Eve wept upon that mount an hundred year, when they were driven out of Paradise, and that water, they say, is of their tears; for so much water they wept, that made the foresaid lake. And in the bottom of that lake men find many precious stones and great pearls. In that lake grow many reeds and great canes; and there within be many cocodrills and serpents and great water-leeches. And the king of that country, once every year, giveth leave to poor men to go into the lake to gather them precious stones and pearls, by way of alms, for the love of God that made Adam. And all the year men find enough. And for the vermin that is within, they anoint their arms and their thighs and legs with an ointment made of a thing that is clept lemons, that is a manner of fruit like small pease; and then have they no dread of no cockodrills, ne of none other venomous vermin . . . In that country and others thereabout there be wild geese that have two heads. (

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville,

chapter 21)

Taprobane, on the other hand, according to Mandeville, is under the rule of Prester John. Mandeville had not yet sited Prester John’s realm in Ethiopia, as he would later do, and it was still in the area of India—though Prester John’s India was often confused with the farthest Orient, the land of earthly paradise. In any event, Taprobane is to be found in the vicinity of India (and he names the point where the Red Sea flows into the ocean). Like Isidore’s account, the island has two summers and two winters and there are enormous mountains of gold guarded by pismires, or giant ants:

These pismires be great as hounds, so that no man dare come to those hills for the pismires would assail them and devour them anon. So that no man may get of that gold, but by great sleight. And therefore when it is great heat, the pismires rest them in the earth, from prime of the day into noon. And then the folk of the country take camels, dromedaries, and horses and other beasts, and go thither, and charge them in all haste that they may; and after that, they flee away in all haste that the beasts may go, or the pismires come out of the earth. And in other times, when it is not so hot, and that the pismires rest them not in the earth, then they get gold by this subtlety. They take mares that have young colts or foals, and lay upon the mares void vessels made there-for; and they be all open above, and hanging low to the earth. And then they send forth those mares for to pasture about those hills, and with-hold the foals with them at home. And when the pismires see those vessels, they leap in anon: and they have this kind that they let nothing be empty among them, but anon they fill it, be it what manner of thing that it be; and so they fill those vessels with gold. And when that the folk suppose that the vessels be full, they put forth anon the young foals, and make them to neigh after their dams. And then anon the mares return towards their foals with their charges of gold. (

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville,

chapter 33)

From this point onward, from one map to the next, Taprobane moves about from one place in the Indian Ocean to another, sometimes alone, sometimes duplicating Ceylon. For a certain period it is identified with Sumatra, but sometimes we find it between Sumatra and Indochina, close to Borneo.

Thomas Porcacchi, in

Isole più famose del mondo

(1572), tells us about a Taprobane full of riches, about its elephants and its immense turtles, as well as the characteristic attributed by Diodorus Siculus to its inhabitants—a kind of forked tongue (“double as far as the root and divided; with one part they talk to one person, with the other they talk to another”).

After having recounted various folk stories, he then apologizes to readers for the fact that he has found no exact reference as to its geographical position, and concludes, “Although many ancient and modern writers have referred to this island, I find no one however who indicates its boundaries: hence I too will have to be excused if in this my usual order is lacking.” As for the island of Taprobane’s identification with Ceylon, he is doubtful: “She was first (according to Ptolemy) called Simondi, and then Salice, and finally Taprobane; but people nowadays conclude that today she is called Sumatra, though there are also those according to whom Taprobane is not Sumatra but the island of Zeilam . . . But some people now suggest that none of the ancients have positioned Taprobane correctly: indeed they hold that where they have put it there is no island at all that can be believed to be that.”

From being

one island too many,

Taprobane therefore slowly became an

island that doesn’t exist.

Thomas More would treat it thus when he situated his Utopia “between Ceylon and America,” and Tommaso Campanella was to use Taprobane as the place where he built his City of the Sun.

Let us now turn to islands whose absence has encouraged (sometimes sporadic) research and an enduring nostalgia.

Ancient epics, of course, tell us about islands that may or may not have existed, so that the isles visited by Ulysses have produced a scholarly literature aimed at establishing which actual places they refer to. And the myth of Atlantis has led to an investigation that is not yet over (judging from the number of mystery magazines and second-rate television programs). But Atlantis was regarded rather more as an entire continent, and the idea was immediately accepted that it had sunk into the sea. It is therefore the subject of legend rather than research.

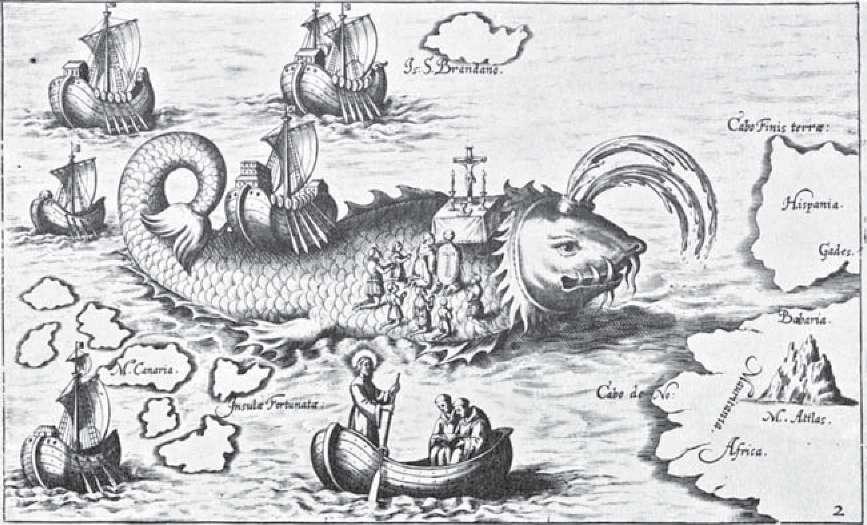

Navigatio Sancti Brendani

was perhaps the first account of the quest for an island.

Saint Brendan and his mystical mariners visited many: the island of birds, the island of hell, the island reduced to a rock on which Judas is chained, and that bogus island that had already deceived Sinbad, on which Brendan’s ship lands—not until the following day, when the ship’s crew light fires and see the island stir in annoyance, do they realize it is not an island but a terrible sea monster called Jasconius.