Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (19 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Neither, though, played in Brazil’s opening game, an unexceptional 3-0 win over Austria. Pelé was injured, while Garrincha had fallen out of favour for showboating in a warm-up friendly against Fiorentina (having rounded the goalkeeper he decided not to roll the ball into an empty net, but to wait for him to recover, upon which he beat him again before walking the ball over the line). Yet Feola, it seems would have played him, had Santos not warned about the strength of the four midfielders in Austria’s W-M. Feola could rely on Mario Zagallo to track back on the left - he, in effect, fulfilled the Orsório role - but that was not Garrincha’s natural game, and so he turned instead to the more disciplined Joel of Flamengo.

They were also omitted against England, who were themselves experimenting with backroom staff - an indication of the growing professionalism of the game across the world. The Tottenham manager Bill Nicholson was sent to scout Brazil, and he concluded the way to stop Brazil was to stop Didi. On his suggestion, the England manager Walter Winterbottom - in a move almost without precedent - made tactical changes to counter Brazil’s threat. The lanky Don Howe, a full-back at West Bromwich Albion, was brought in to play as a second centre-half alongside Billy Wright, with Thomas Banks and Eddie Clamp, a right-half at Wolves, operating as attacking full-backs on either side of them, and Bill Slater deputed to sit tight on Didi. Vavá hit the bar, Clamp cleared one off the line and Colin McDonald twice produced fine saves to keep out headers from José Altafini (who was still going by the nickname of Mazzola), but the system dulled Brazil, and England got away with a goalless draw.

That left Brazil needing to beat the USSR in their final group game to be sure of progression to the last eight. Carvalhães conducted further tests, asking the players to draw the first thing that came into their heads. Garrincha produced a circle with a few spokes radiating from it. It looked vaguely like a sun, but when Carvalhães asked what it was supposed to be, Garrincha replied that it was the head of Quarentinha, a team-mate at Botafogo. Carvalhães promptly ruled him out. In total, of the eleven who would eventually start against the USSR, he judged nine unsuitable for such a high-pressure game. Fortunately Feola trusted his own judgement, and selected both Pelé and Garrincha. ‘You may be right,’ Pelé recalls him saying to Carvalhães. ‘But the thing is, you don’t know anything about football.’

Feola was concerned by reports of the Soviets’ supreme fitness, and had decided that his side had to intimidate them with Brazilian skill from the off. ‘Remember,’ he said to Didi just before he left the dressing room, ‘the first pass goes to Garrincha.’

It took a little under twenty seconds for the ball to reach the winger. Boris Kuznetsov, the experienced Soviet left-back, moved to close him down. Garrincha feinted left and went right; Kuznetsov was left on the ground. Garrincha paused, and beat him again. And again. And then once again put him on the ground. Garrincha advanced, leaving Yuri Voinov on his backside. He darted into the box, and fired a shot from a narrow angle that smacked against the post. Within a minute Pelé had hit the bar, and a minute after that, Vavá gave Brazil the lead from Didi’s through-ball. Gabriel Hanot called them the greatest three minutes of football ever played.

Brazil won only 2-0, but the performance was every bit as special as the demolitions of Spain and Sweden had been eight years earlier. Wales offered surprising resistance in the quarter-final, even without the imposing presence of the injured John Charles, and lost only 1-0, but this Brazil side could not be denied. France, hampered by an injury to Bob Jonquet, were brushed aside 5-2 in the semi-final, and Sweden went down by the same score in the final. ‘There was no doubt this time,’ Glanville wrote, ‘that the best, immeasurably the finest, team had won.’

It was, Feola said, Zagallo’s role, balancing the anarchic brilliance of Garrincha, that had proved key. Initially an inside-forward, Zagallo had converted himself into a winger because he realised that was his only chance of getting into the national side, and so was ideally suited to the role of tracking back and forth on the left flank. By the 1962 World Cup, he had taken to playing so deep that the system began to be referred to as a 4-3-3. ‘The age factor, in Chile, was one we had always to take into consideration,’ explained Aimoré Moreira, who replaced Feola as his health deteriorated but picked a similar squad for the following World Cup. ‘That was responsible for our tactics being less flexible than some, remembering the team’s sparkle in Sweden, expected. In Chile we had strictly to employ each player in accordance with what we knew about the yield of the whole team. For example, Didi was more and more a player good at waiting in midfield, and blocking the centre to the opponents… Zito, quicker, more dynamic, was able to shuttle backwards and forwards, and could last out a full ninety minutes while doing this. This meant, because of the need carefully to relate the role of one to the other, the elasticity of attacks was limited - with this one great compensation, that every player was free and had the ability to use his own initiative, and make variations.’

The greatest compensation of all was Garrincha. Opponents regularly set two or even three men to mark him, and he simply bypassed them. Pelé played only the opening two matches in Chile before injury ended his involvement, but Garrincha was enough. He missed a penalty but scored twice as England were seen off 3-1 in the quarter-final, and scored two more and was sent off in a 4-2 victory over Chile in the semi. Reprieved for the final, he was relatively subdued, but it didn’t matter: 1962 had been his tournament, the final triumph of the winger before the culls of the mid-sixties.

In a piece in

A Gazeta

in 1949, Mazzoni wrote that, ‘For the Englishman, football is an athletic exercise; for the Brazilian it’s a game.

‘The Englishman considers a player that dribbles three times in succession is a nuisance; the Brazilian considers him a virtuoso.

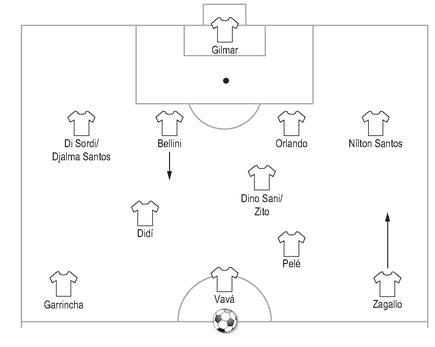

Brazil, 1958 World Cup

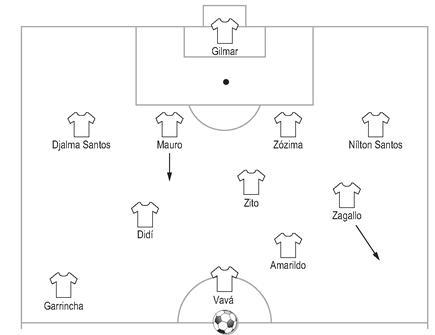

Brazil, 1962 World Cup

‘English football, well played, is like a symphonic orchestra; well played, Brazilian football is like an extremely hot jazz band.

‘English football requires that the ball moves faster than the player; Brazilian football requires that the player be faster than the ball.

‘The English player thinks; the Brazilian improvises.’

There was nobody who exemplified the difference more than Garrincha. At São Paulo, Guttmann had had a left-winger called Canhoteiro, who was regarded as the left-footed Garrincha (the name translates as ‘left-footed’). ‘Tactics,’ Guttmann once said after seeing Canhoteiro ignore him brilliantly once again, ‘are for everybody, but they are not valid for him.’ The beauty of playing four at the back was that, although it wasn’t predicated on such players - as Viktor Maslov and Alf Ramsey would prove - it provided an environment in which they could thrive. The world soon got the message, and by the time of the 1966 World Cup, the W-M had all but passed into history.

Chapter Eight

The English Pragmatism (1)

∆∇ ‘You in England,’ Helenio Herrera announced at an impromptu press conference at Birmingham Airport in March 1960, ‘are playing in the style we continentals used so many years ago, with much physical strength, but no method, no technique.’ No one who had seen his Barcelona side deconstruct Wolverhampton Wanderers, the English champions, the night before could have been in much doubt that he was right. Barcelona, already 4-0 up from the first leg, had dazzled in the second, completing a 9-2 aggregate victory. The days of the floodlit friendlies, in which Wolves had beaten the likes of Honvéd and Spartak Moscow, seemed an awfully long time ago.

Wolves, in fairness, were more direct than most, but Herrera believed the fact they had been so dominant domestically was evidence of a more general weakness in the English game. ‘When it came to modern football, the Britons missed the evolution,’ he said, mocking their instinctive conservatism. ‘The English are creatures of habit: tea at five.’ The irony of that is that Stan Cullis, the Wolves manager, was actually one of England’s more progressive thinkers.

The heavy defeats to Hungary had made clear that any notion of English superiority was a myth, and there was at least a recognition that the English style had to change, as is demonstrated by the publication of a slew of books lamenting the passing of a golden age. The problem was that nobody seemed too sure how to go about it. The W-M was widely blamed, but remained the default. In as much as solutions were suggested, they tended to follow the course prescribed by Willy Meisl in

Soccer Revolution

: go back to the golden age and readopt the 2-3-5; which tended, of course, rather to prove Herrera’s point: as the rest of the world became increasingly tactically sophisticated, there were serious and influential football writers in Britain advocating a return to a formation that had looked outmoded twenty years earlier.

The option of copying Hungary was something that was only really considered at Manchester City. Johnny Williamson had had success playing as a deep-lying centre-forward in the reserve side at the end of the 1953-54 season and, the following year, the manager Les McDowall had Don Revie play there for the first team. Revie subsequently devoted twenty pages of his memoir,

Soccer’s Happy Wanderer

, to explaining the system. After an uncertain start - they were beaten 5-0 by Preston on the opening day of the season - and some difficult times on the heavy pitches of the winter, City went on to reach the Cup final and finish seventh, while Revie was named Footballer of the Year. That summer, though, Revie took a family holiday in Blackpool against the wishes of the club and, after being suspended for the opening fortnight of the season, remained on the periphery. Injuries restored him to the line-up for the FA Cup final, in which City beat Birmingham, but Revie had become disillusioned and joined Sunderland the following season.

City reverted to more traditional methods, while Revie struggled to settle at Roker Park. Locked in a spiral of reckless spending, Sunderland then tumbled into an illegal payments scandal, as they were found to be offering win bonuses of £10, when the stipulated maximum was £4. Amid the chaos, as their manager Bill Murray was replaced by Alan Brown, Sunderland were relegated. Revie, anyway, may not have adapted. ‘There was only one way he could play,’ said Sunderland’s inside-right Charlie Fleming. ‘He did a lot of things foreign to us… Don’s system was alright in Manchester, but everybody knew about it when he came to Sunderland and how to play against it. Don couldn’t change.’ Or perhaps it was that British players couldn’t change. Either way, Revie soon departed for Leeds, where he was used as an inside-forward, and the momentum of his experiment was lost.

Even those British teams who enjoyed success in the early European Cup tended simply to prosper not through innovation but because they were very good at applying the old model. Hibernian for instance, semi-finalists in the first European Cup, were famed for their Famous Five front line of Gordon Smith, Bobby Johnstone, Lawrie Reilly, Eddie Turnbull and Willie Ormond. The Manchester United of Bobby Charlton, Dennis Viollet and Duncan Edwards, for all their youth and vibrancy, were a side rooted in the W-M. ‘By a combination of short and long passes,’ Geoffrey Green wrote, ‘[they] have discarded a static conventional forward shape and, with the basic essential of a well-ordered defence, have found success by the sudden switching and masking of the final attacking thrust by their fluid approach. This aims at producing a spare man - or “man over” - at the height of the attack.’ Busby’s United may have been fluid in British terms, and their brilliance is not in doubt, but they were still orthodox by European standards.

The most successful radicalism came at Tottenham Hotspur, where Hungarian thinking had taken hold even before the watershed of 1953. Arthur Rowe had lectured in Budapest in 1940, but education had proved a two-way process; after giving the sport to the world, finally there was cross-pollination back into Britain. Thanks to Peter McWilliam, an enlightened coach of the twenties and thirties (Scottish, of course), Tottenham had a historical preference for a close-passing game, something of which Rowe had been part. Although he had played as a deep-lying centre-half for Spurs, Rowe had been a far more rounded player than Herbie Roberts and his many imitators, preferring to hold possession and delay until he could play accurate passes rather than simply hoofing it forwards without design. Working with Hungarians, though, taught him just how far the practice could be extended and when, in 1949, he was appointed as manager of Tottenham, then a second-division side, he set about implementing that style: ‘Make it simple, make it quick,’ as he always urged.

Almost his first act was to sign Alf Ramsey, at the time noted as a forward-thinking right-back at Southampton. In

And the Spurs Go Marching On

, Rowe explains how he had admired Ramsey’s willingness to attack, but encouraged him not to rely so heavily on long forward passes. ‘Had he [Ramsey] ever thought how much more accuracy was guaranteed, how much more progress could be made if he pumped 15- or 20-yard passes to a withdrawn [outside-right Sonny] Walters. The opposing left-back would hesitate to follow Walters back into the Spurs half, which was definitely no man’s land to the full-back then, thus giving Walters the vital gift of space. And Sonny could now make an inside pass if Alf followed up and made himself available.’

Almost uniquely in Britain, Spurs began building from the back, with Ramsey given licence to push on. ‘There is no limit to where even a defender will go to attack,’ he said. ‘Maybe you have noticed how often I go upfield to cross a ball or even have a shot at goal. That a defender should not attempt to score a goal is something to which I can never subscribe.’ He could only do that, though, because his centre-half, Bill Nicholson, as dour a player as he was a public speaker, was prepared to sit in and provide cover.

At times during that 1950-51 season, their first back in the top flight, Spurs were magnificent. After a 7-0 win over Newcastle in the November, for instance, the

Telegraph

was moved to write that ‘Tottenham’s method is simple. Briefly, the Spurs principle is to hold the ball a minimum amount of time, keep it on the ground and put it ahead into an open space where a colleague will be a second or two later. The result is their attacks are carried on right through the side with each man taking the ball in his stride at top pace, for all the world like a wave gathering momentum as it races to the far distant shore. It is all worked out in triangles and squares and when the mechanism of it clicks at speed, as it did on Saturday, with every pass placed to the last refined inch on a drenched surface, there is simply no defence against it.’ They won the title by four points, and were still playig a similar style when they did the Double ten years later.

Such progressiveness was rare in England, though, and Spurs were regarded with suspicion, despite their success.

As the rest of the world developed technically, and worked out increasingly sophisticated defensive patterns or means of structuring fluidity, British football ploughed its own, less subtle, furrow. In its own way, it was just as rooted in fear - or, to its apologists, pragmatism - as the

catenaccio

Herrera would eventually adopt, but this was a very British insecurity. Skill, or anything that required thinking too much, was not to be trusted, while physical toughness remained the ultimate virtue. It is no coincidence that, the World Cup triumph of 1966 aside, the iconic image of English football remains a blood-soaked Terry Butcher, bandaged but unbowed after inspiring England to the goalless draw against Sweden that ensured qualification for the 1990 World Cup. Even the manner of that stalemate was characteristic. Italy might have set out to kill the game, passing the ball at deathly pace around midfield, wasting time, breaking the rhythm - as England in fact did in a scarcely credible role reversal against Italy in Rome in 1997. In Stockholm in 1989, though, England simply sat back, defended deep, and relied on courage under fire: what Simon Kuper has called the urge to recreate Dunkirk at every opportunity.

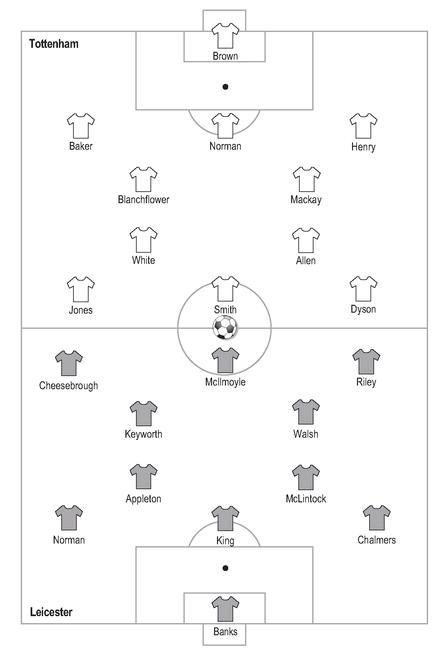

Tottenham Hotspur 2 Leicester City 0, FA Cup Final, Wembley, May 6, 1961

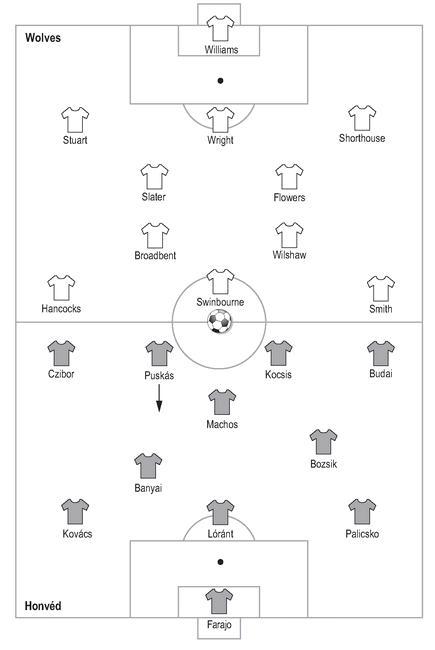

Wolves 3 Honvéd 2, friendly, Molineux, Wolverhampton, 13 December 1954

To blame Cullis for a trait that has run through English football from its earliest origins would be nonsensical, just as it was for writers in the fifties to blame Chapman (or even, as Willy Meisl did, on the basis of a hint supposedly dropped in a conversation with his brother, to persist in the wishful thinking that, had Chapman not died when he did, he would have reverted to a more classical system). Besides, if results rather than aesthetics are the goal, there is nothing necessarily wrong with functional physicality; thirteen years after the Hungary debacle, it would, after all, win England a World Cup. What is important, is the method and the thought behind it.

Cullis’s side might have been overwhelmed by Herrera’s Barcelona, but they had achieved notable results against elite sides only a few years earlier. Floodlights were installed at Molineux in the summer of 1953, and officially turned on for a game against a South Africa national side that September. Racing Club of Buenos Aires were beaten 3-1, a game in which ‘Wolverhampton Wanderers efficiently demonstrated that English soccer played with speed and spirit is still world class’, according to the ever-opinionated Desmond Hackett in

The Express

. Wolves then beat Dinamo Moscow 2-1 and Spartak 4-0, but the most memorable match, without question, was the meeting with the Honvéd of Puskás, Czibor, Bozsik and Kocsis on 14 December 1954. After the two humiliations Hungary had inflicted on England, this was a chance for revenge.

On the morning of the game, Cullis, remembering how Hungary had struggled in the mud in the World Cup final against West Germany that summer, sent out three apprentices - one of them a sixteen-year-old Ron Atkinson - to water the pitch. ‘We thought he was out of his mind,’ Atkinson said in an interview quoted in Jim Holden’s biography of Cullis. ‘It was December and it had been raining incessantly for four days.’