Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (39 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Whatever the origins, a 1-3-3-3 with man-marking and the libero as a true free man became the default in German football, and, with the minor modification of one of the forwards being withdrawn into a playmaking role, it was still essentially that system that Beckenbauer, by then their coach, had West Germany use in Mexico in 1986. In the quarter-final, for instance, when they beat the hosts on penalties, Ditmar Jakobs played as the sweeper with, from right to left, Andreas Brehme, Karl-Heinz Förster and Hans-Peter Briegel in front of him. Thomas Berthold, Lothar Matthäus and Norbert Eder made up the midfield, with Felix Magath as the playmaker behind Karl-Heinz Rummenigge and Klaus Allofs.

For the semi-final against France, though, which was won 2-0, West Germany also went with three central defenders, as Eder dropped in alongside Förster and Wolfgang Rolff came into midfield to perform a man-to-man marking job on Michel Platini. Beckenbauer instructed Förster to remain deep, and so, as the defender said, ‘we ended up playing zonal marking almost by default’. It would be another decade before the debate was properly addressed in German football.

With Rolff standing down for the return of Berthold from suspension, the job of man-marking Maradona was given to Matthäus in the final. West Germany stuck with the 3-5-2 and Maradona was kept relatively quiet, but he also neutralised Matthäus, dragging him so deep that it was though West Germany had four central defenders. With two holders in front of the back line, that left them shorn of creativity and left Magath isolated, with the result that he was barely involved.

West Germany’s narrowness - and their system didn’t even allow the full-backs to push on - played into Argentina’s hands. Brown headed them in front after Schumacher had flapped at a corner, and when Valdano calmly added a second eleven minutes into the second half, the game seemed won. Only then was Matthäus released from his marking duties, and only then did West Germany begin to play, exposing a weakness that had tormented Bilardo. Set-plays were supposed to be his speciality, but he was so anxious about his side’s ability to defend them that, at 4 a.m. on the morning of the final, he burst into Ruggeri’s room, pounced on him, and, with the defender disoriented and half-asleep, asked who he was marking at corners. ‘Rummenigge,’ came the instant reply, which Bilardo took as evidence that Ruggeri was sufficiently focused.

With sixteen minutes to go, though, and with Brown nursing a fractured shoulder, Rudi Völler glanced on a corner for Rummenigge to score. Eight minutes later, Berthold headed another corner back across goal and Völler levelled. Perhaps having done so, West Germany should have gone back into the negativity their system seemed to demand, but they did not. The momentum was with them and, at last, they left space in behind their defence. It took Maradona just three minutes to exploit it, laying a pass beyond Briegel for Burruchaga to run on and score the winner.

Looking back, their success seems almost freakish and, while the jibes they were a one-man team were unfair, the dangers of being quite so reliant on Maradona were seen as Argentina won only six of the thirty-one games they played between the end of that World Cup and the start of the next one. They went on, somehow, to reach the final. Bilardo did not win many games as national coach, but he did have a habit of winning the ones that mattered. Moreover, his thinking came to seem axiomatic. By Italia ’90, three at the back was a common sight.

Argentina 3 West Germany 2, World Cup final, Azteca, Mexico City, 29 June 1986

The champions, West Germany, employed the formation, with Klaus Augenthaler, Guido Buchwald and either Berthold or Jürgen Kohler providing the foundations for a midfield trio of Matthäus plus two of Buchwald, Thomas Hässler, Uwe Bein, Pierre Littbarski and Olaf Thon, depending on circumstance. That was the beauty of the system - it allowed changes of tone to be made simply, without great wrenches of shape. Against Holland in the second round, for instance, Buchwald, usually a central defender, was used a midfielder to help break up the Dutch passing game.

For Brazil, it required only minor modification, one of the two holding players in their 4-2-2-2 becoming a third centre-back, although they never seemed to have much confidence in the formation and were generally uninspired, losing 1-0 to Argentina in the second round. More surprisingly, even England adopted the

libero

, almost as a last resort after they began the competition with a 1-1 draw against the Republic of Ireland so bad that the

Gazzetta della Sport

reported it under the headline ‘No football, please, we’re British.’

With Mark Wright as a sweeper, flanked by Terry Butcher and Des Walker, England felt able to deploy the attacking talents of Chris Waddle, David Platt and Paul Gascoigne in the same midfield. They may have been fortuitous at times, but the outcome was that, in a paradox that seemed to blind England fans to the wider truths of that tournament, they played with greater adventure than for years and reached a semi-final for the first time since 1966. There, they were good enough to match West Germany before losing on penalties.

Still, that was not a good World Cup. Goals were down to a record low of 2.21 per game; red cards up to a record high of sixteen. Even West Germany, clearly the best side there, managed just three goals in their final three games: two penalties and a deflected free-kick. Theirs was a team built predominantly on muscle, something the 3-5-2 seemed to encourage. Johan Cruyff despaired of it, later speaking of the replacement of the winger with the wing-back as the ‘death of football’.

This was the result of the other facet of Bilardo’s thinking coming into play: that the best place for a playmaker was perhaps not in the midfield, but as a second forward. His insistence on three players and seven runners may have been extreme, but the balance certainly tipped in that direction. Even Holland in 1988 ended up deploying Ruud Gullit, who would surely once have been a deeper-lying player, as a second striker behind Marco van Basten in a 4-4-1-1.

As players became fitter and systems more organised, defences became tighter. The idealism of the Brazilians faded, and the playmaking second striker morphed into a fifth midfielder. After the sterility of the 1990 World Cup, the low point came in the European Championship of 1992, a festival of dullness that yielded an average of just 2.13 goals per game. Even as Fifa desperately changed the rules to outlaw the backpass and the challenge from behind, football seemed to have embarked on an endless march away from the aesthetic. With the game so well analysed and understood, and defensive strategies so resolute, by the early nineties the great question facing football was whether beauty could be accommodated at all.

Chapter Fifteen

The English Pragmatism (2)

∆∇ As so often, progress began with defeat. Chris Lawler’s goal in a 2-1 loss in the first leg in the Marakana had given Liverpool hope of overcoming Red Star Belgrade in the second leg and reaching the quarter-final of the 1973-74 European Cup, but at Anfield, Red Star, under the guidance of Miljan Miljanić, played a brilliant counter-attacking game and struck twice on the break through Vojin Lazareviç and Slobodan Janković to complete a 4-2 aggregate win.

The following day, 5 November 1973, in a cramped, windowless room just off the corridor leading to the Anfield dressing room, six men set in motion the stylistic shift that led English clubs to dominate Europe in the late seventies and early eighties. The boot-room, as history would know it, was not an obvious place to plot a revolution. It was small and shabbily carpeted, hung on one side with hooks for players’ boots and decorated with team photographs and topless calendars. Joe Fagan, the first-team coach under Bill Shankly, had begun the tradition of post-game discussions there, stocking the room with crates of beer supplied by the chairman of Guinness Exports, whose works team he had once run in nearby Runcorn. Initially he met only with Bob Paisley, in those days the team’s physiotherapist, but gradually other members of the club’s backroom staff began to drop in. ‘You got a more wide-ranging discussion in the boot-room than the boardroom,’ Paisley said. ‘What went on was kept within those four walls. There was a certain mystique about the place.’ Managers of opposing teams willing to offer information and opinions about players were invited, and even Elton John visited during his time as Watford chairman. When offered a drink, Anfield legend has it, he asked for a pink gin; he was given a beer.

Gradually the boot-room grew in importance, becoming effectively a library where coaches could refer to books in which were logged details of training, tactics and matches. In

Winners and Losers: The Business Strategy of Football

, the economist Stefan Szymanski and the business consultant Tim Kuypers claimed Liverpool’s success in the seventies and eighties was a result of their organisational structure, of which the boot-room was a key part. ‘The boot-room,’ they wrote, ‘appears to have been some kind of database for the club, not merely of facts and figures, but a record of the club’s spirit, its attitudes and its philosophy.’

On Bonfire Night 1973, though, the greater part of that success was still to come, and Liverpool seemed to have reached an impasse. Red Star, European Cup semi-finalists in 1970, were a useful side, of that there was no question, but the manner of their victory seemed to point to a more essential deficiency than the vagaries of form. So a meeting was convened, Shankly, Fagan and Paisley being joined in the boot-room by Ronnie Moran, the reserve team coach, by Tom Saunders, the head of youth development, and by the chief coach Reuben Bennett, a dour Scottish disciplinarian famed for his habit of telling injured players to rub away the pain with a wire-brush or a kipper.

They weren’t crisis talks exactly, but the issues they discussed were fundamental: just why did Liverpool, imperious domestically, look so vulnerable in Europe? Despite the background of English underachievement, it is a mark of Shankly’s perfectionism that a flaw was perceived at all. After all, Liverpool had won the Uefa Cup the previous season, beating Borussia Mönchengladbach 3-2 on aggregate in the final. In the years before that success, though, Liverpool had gone out of European competition to the likes of Ferencváros, Athletic Bilbao and Vitória Setúbal, none of them complete minnows, but none of them the cream of Europe, either. If the Uefa Cup triumph suggested Liverpool had found a solution, the defeat to Red Star emphatically disabused them.

‘They are a good side,’ Shankly said, ‘even though our fans would not pay to watch the football the play.’ The way they were prepared to hold possession and frustrate their opponents, though, taught Liverpool an important lesson. ‘We realised it was no use winning the ball if you finished up on your backside,’ said Paisley. ‘The top Europeans showed us how to break out of defence effectively. The pace of their movement was dictated by their first pass. We had to learn how to be patient like that and think about the next two or three moves when we had the ball.’

The days of the old-fashioned stopper centre-half, the boot-room decided, were over: it was necessary to have defenders who could play. Larry Lloyd, exactly the kind of central defender they had declared extinct (although he would later enjoy an unlikely renaissance at Nottingham Forest), then ruptured a hamstring, and Phil Thompson, originally a midfielder, was pushed back to partner Emlyn Hughes at the heart of the defence. ‘The Europeans showed that building from the back is the only way to play,’ Shankly explained. ‘It started in Europe and we adapted it into our game at Liverpool where our system had always been a collective one. But when Phil Thompson came in to partner Hughes it became more fluid and perhaps not as easy to identify. This set the pattern which was followed by Thompson and [Alan] Hansen in later years.

‘We realised at Liverpool that you can’t score a goal every time you get the ball. And we learned this from Europe, from the Latin people. When they play the ball from the back they play in little groups. The pattern of the opposition changes as they change. This leaves room for players like Ray Kennedy and Terry McDermott, who both played for Liverpool after I left, to sneak in for the final pass. So it’s cat and mouse for a while waiting for the opening to appear before the final ball is let loose. It’s simple and it’s effective… It’s also taken the spectators time to adjust to it.’

Shankly was no great tactician - he tended to leave that side of the game to Paisley, and was so bored when he did attend a week-long coaching course at Lilleshall that he left on the Tuesday - but from the moment of his arrival at Liverpool, he had a clear sense of the general style his wished to play. ‘Shankly,’ said a piece in the

Liverpool Echo

from December 1959, ‘is a disciple of the game as it is played by the continentals. The man out of possession, he believes, is just as important as the man with the ball at his feet. Continental football is not the lazy man’s way of playing soccer. Shankly will aim at incisive forward moves by which continentals streak through a defence when it is “closed up” by British standards. He will make his players learn to kill a ball and move it all in the same action… he will make them practise complete mastery of the ball.’

That might have been overstating it, but Shankly certainly had a belief in the value of control almost as profound as Jimmy Hogan’s. At the Melwood training ground, he set up four boards to form a square. A player would stand in the middle, and would be called upon either to strike first time or to trap balls flung at him from the four corners.

‘Above all,’ Shankly said, ‘the main aim is that everyone can control a ball and do the basic things in football. It’s control and pass … control and pass … all the time. At the back you’re looking for someone who can control the ball instantly and give a forward pass. It gives them more space and time to breathe. If you delay, the opposition have all run back behind the ball. It’s a very simplified affair and, of course, very economical.

‘At Liverpool we don’t have anyone running into no man’s land, running from their own half with the ball into the opposition half. That’s not encouraged at all. That’s nonsense. If you get a ball in the Liverpool team you want options, you want choices … you want at least two people to pass to, maybe three, maybe more… Get the ball, give an early pass, then it goes from me to someone else and it switches around again. You might not be getting very far, but the pattern of the opposition is changing. Finally, somebody will sneak in.’

The side that won the championship in 1964 played an orthodox W-M, but Shankly was prepared to make changes. The following season, Liverpool faced Anderlecht in the second round of the European Cup, shortly after England had played a friendly against a Belgium side featuring seven Anderlecht players. Shankly was at Wembley to see the game, and recognised the attacking threat posed by the likes of Paul van Himst and Jef Jurion. It was his decision to switch to red shorts for the game - the first time Liverpool had worn all red - that caught most of the attention, but just as significant was his ploy of withdrawing an inside-forward to use Tommy Smith as an auxiliary central defender; an early example of an English club side using four at the back.

That suggested a flexibility, an awareness that the English way wasn’t the only way, but Paisley admitted, ‘Our approach was a bit frantic. We treated every match like a war. The strength of British football lay in our challenge for the ball, but the continentals took that away from us by learning how to intercept.’ It was that fault that the Bonfire Night revolution of 1973 corrected, and after Paisley had replaced Shankly in 1974, Liverpool would come to be defined by their patient passing approach. It took them to four European Cups between 1977 and 1984, and it was with a similar approach that Nottingham Forest under Brian Clough lifted their two European Cups.

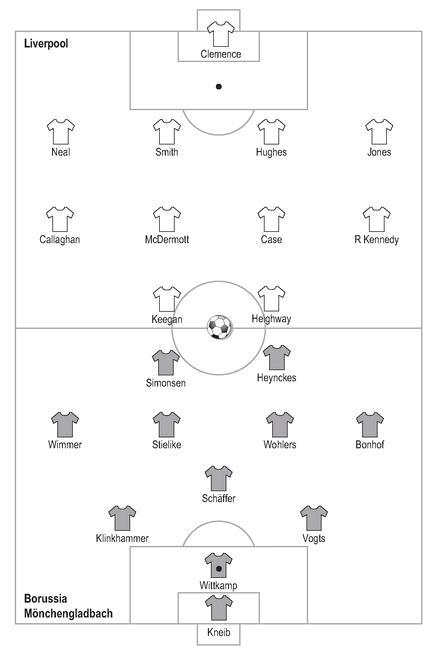

Liverpool 3 Borussia Mönchengladbach 1, Olimpico, Roma, 25 May, 1977

While they espoused a possession-based passing game, there was at the same time a strand of English football that went in the opposite direction, and favoured a high-octane style readily dismissed as kick-and-rush. It was the basis to the rise of Watford and Wimbledon, small clubs who learned to punch above their weight, but, damagingly, it became orthodoxy at the Football Association. When Charles Hughes became technical director of the FA, English football was placed into the hands of a fundamentalist, a man who, Brian Glanville claims, ‘poisoned the wells of English football’.

Hughes still has plenty of apologists, but even if Glanville’s assessment is correct, the achievements of Watford and Wimbledon should not be decried - or at least, not on the grounds of directness alone. In English football, the seventies is remembered as the age of the mavericks, of the likes of Alan Hudson, Frank Worthington and Stan Bowles, individuals who did not fit into the increasingly systematised schema that had become the vogue since Ramsey’s success in the World Cup. The historically more significant feature of the decade, though, was the introduction of pressing.

It came from a surprising source: a young manager who began his career with Lincoln City, and then brought, given the resources available to him, staggering success to Watford: Graham Taylor. England’s failure to qualify for the World Cup in 1994 and the vilification that followed has rather sullied his reputation, but in the late seventies he was the most radical coach in the country. There were those who dismissed him as a long-ball merchant, but as he, Stan Cullis and a host of managers stretching back to Herbert Chapman have pointed out, it is simply impossible for a team to be successful if all they are doing is aimlessly booting the ball forwards. ‘When,’ as Taylor asked, ‘does a long pass become a long ball?’

Many coaches have prospered after less than stellar playing careers - indeed, for the truly revolutionary, it appears almost a prerequisite - but Taylor seems to have known almost from the start that his future lay in the coaching rather than the playing side of the game. ‘The intention had been to stay on at school, do A-levels and become a teacher,’ he said. ‘I left after a year of sixth-form to become a footballer, but I was still interested enough in my education to do a coaching badge, so I was qualified by the time I was twenty-one. I was always reading and looking for ideas.’ One of the ideas he seized upon was pressing, the possibilities of which became clear to him after he had read a series of articles about Viktor Maslov in the Football Association’s in-house coaching magazine.

Taylor spent four years at Grimsby Town, before moving on to Lincoln City. He became a fully-qualified FA coach at twenty-seven - the youngest man to do so - and, after a hip injury had curtailed his playing career, was twenty-eight when he took over as manager in 1972. Four years later, Taylor led Lincoln to the Fourth Division title, setting new records for most points, most wins and fewest defeats as he did so.