Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (49 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Arrigo Sacchi is adamant that there have been no innovations since his Milan and, while there is self-interest in his claims, there is also a large degree of truth to them. Perhaps more significant, though, is his attitude to the likes of Makélélé. Sacchi is sceptical about the 4-2-3-1 and the modern 4-3-3 with its designated holder because, to him, they are too restrictive. ‘Today’s football is about managing the characteristics of individuals,’ he said. ‘And that’s why you see the proliferation of specialists. The individual has trumped the collective. But it’s a sign of weakness. It’s reactive, not pro-active.’

Mourinho’s Chelsea

That, he believes, was the fundamental flaw in the

galacticos

policy at Real Madrid, where he served as director of football between December 2004 and December 2005 as the club signed a host of stars and tried to balance them with hard runners from the youth set-up. ‘There was no project,’ he explained. ‘It was about exploiting qualities. So, for example, we knew that Zidane, Raúl and Figo didn’t track back, so we had to put a guy in front of the back four who would defend. But that’s reactionary football. It doesn’t multiply the players’ qualities exponentially. Which actually is the point of tactics: to achieve this multiplying effect on the players’ abilities.

‘In my football, the

regista

- the playmaker - is whoever had the ball. But if you have Makélélé, he can’t do that. He doesn’t have the ideas to do it, although, of course, he’s great at winning the ball. It’s become all about specialists. Is football a collective and harmonious game? Or is it a question of putting x amount of talented players in and balancing them out with y amount of specialists?’

When he returned to AC Milan in 1996 after his stint in charge of the national team, Sacchi ensured that Marcel Desailly, who had been used in midfield by Fabio Capello, was returned to the defensive line. Like Valeriy Lobanovskyi, for whom he professes a great admiration, Sacchi believes in the benefits of universality, in players who are not tied by their limitations to certain roles, but who can roam, taking as a reference for their positioning their team-mates, their opponents and the available space as much as the pitch. When that is achieved the system is truly fluid.

That, of course, is precisely what the new breed of wingers and playmakers offer. They are not merely creators, but also runners and, to a degree, defenders. As

fantasistas

have evolved, so other positions have changed. It is very rare, for instance, to find a top side that plays with two stopper centre-backs. There is a need always for at least one who can pass the ball, or advance with it into midfield. More strikingly, the sniffer centre-forward has all but vanished. ‘Those half-chances that poachers used to seize on don’t exist any more,’ explained Zoran Filipović, once a striker with Red Star, later their coach, and then the first manager of an independent Montenegro. ‘Defences are organised better, players are fitter. You have to create chances; you can’t rely on mistakes.’

Filippo Inzaghi is among the last of a dying breed, but at least obsolescence crept up on him toward the end of his career; Michael Owen was in his mid-twenties when it became apparent that, however good he is at sitting on the shoulder of the last defender or darting across the near post, it is not enough in modern football. ‘I’ve definitely developed my game, coming off and holding the ball up better and trying to link a bit more, but I’ve got to keep the main thing which is scoring goals and trying to get in behind people,’ he said. ‘The main aim at the end of the day is to put the ball in the back of the net.’

The attitude is typically English and one that is a great source of frustration to managers. ‘I can’t believe that in England they don’t teach young players to be multi-functional,’ Mourinho said. ‘To them it’s just about knowing one position and playing that position. To them a striker is a striker and that’s it. For me, a striker is not just a striker. He’s somebody who has to move, who has to cross, and who has to do this in a 4-4-2 or in a 4-3-3 or in a 3-5-2.’

Owen was highly critical of the then-England coach Kevin Keegan’s efforts to expand his repertoire in the build-up to Euro 2000, but the reality may be that putting the ball in the back of the net is no longer sufficient - or, at least, not at the very highest level. Owen could be one of those players who wins teams the occasional game, but prevents them playing good football (which means that he may prove extremely useful to mediocre sides, or even to a good side playing badly, but rarely if at all to a good side playing well). Even allowing for his history of injuries, it is surely significant that when he left Real Madrid in 2005, no Champions League qualifier was prepared to take him on and he ended up at Newcastle. He appears a player left behind by the tactical evolution of the game.

The modern forward, rather, is far more than a goalscorer, and it may even be that a modern forward can be successful without scoring goals. The example of Guivarc’h has already been mentioned, but at Euro 92, Denmark’s two centre-forwards, Fleming Povlsen and Kim Vilfort, were both widely perceived as having had excellent tournaments but scored between them only one goal - and that not until the final. Their job was rather to challenge for long balls, retain possession if they won it, and lay it off for Henrik Larsen and Brian Laudrup, the two more attack-minded midfielders. That seemed at the time an aberration, but it was a sign of things to come.

Goals are obviously part of it - a particularly valuable one - and the non-scoring forward a particular case, but the truly great modern forwards appear rather as a hybrid of the old strike partnerships. The likes of Didier Drogba and Emmanuel Adebayor are both target-man and quick-man, battering-rams and goalscorers, imposing physically and yet also capable of finesse. A Thierry Henry or a David Villa mixes the best qualities of the creator and goalscorer, capable of dropping deep or pulling wide, as adept at playing the final ball as taking chances himself. Somewhere in between the two extremes are ranged Andriy Shevchenko (in his Dynamo Kyiv and Milan days), Zlatan Ibrahimović, Samuel Eto’o and Fernando Torres.

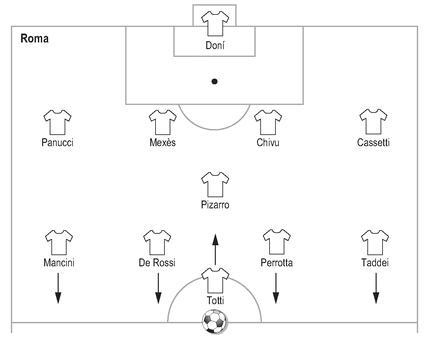

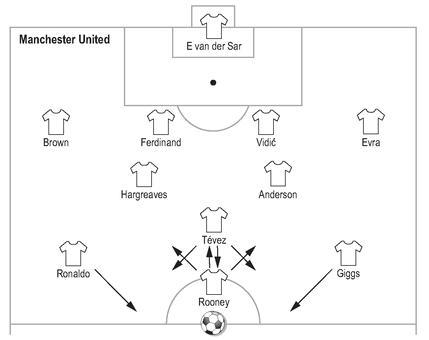

Roma 2006-07, Manchester United 2007-08

Manchester United

Maslov spoke of football being like an aeroplane, becoming increasingly streamlined, but perhaps the gradual adoption of a front-line of one is not quite the end of evolution. Carlos Alberto Parreira, who led Brazil to victory in the 1994 Word Cup and was in charge of them again in 2006, after all, has spoken of the possibilities of a 4-6-0. ‘You’d have four defenders at the back although even they’d be allowed to run forward,’ Andy Roxburgh, the former Uefa technical director, explained. ‘The six players in midfield, all of whom could rotate, attack and defend. But you’d need to have six Decos in midfield - he doesn’t just attack, he runs, tackles covers all over the pitch. You find him playing at right-back sometimes.’

Yet what is Deco but the classic example of Lobanovskyi and Sacchi’s notion of universality? It is notable that in 2005-06, although Frank Rijkaard often deployed the combative Mark van Bommel or the converted central defender Edmílson in the Champions League, in La Liga he regularly played a midfield three of Deco, Xavi and Andrés Iniesta, all of whom are under 5′9″ and none of whom are exactly terrifying physical presences. Industrious players properly organised don’t need to intimidate by size.

Slowly, it seems, Parreira’s vision is beginning to become reality. In 2006-07, for instance, Luciano Spalletti’s Roma played a 4-1-4-1, but with Francesco Totti, the archetypal

trequartista

, as the lone striker. David Pizarro operated as the holding player, with Taddei, Simone Perrotta, Daniele De Rossi and Mancini in front of him. What regularly happened, though, was that Totti dropped deep into the

trequartista

position in which he’d spent so much of his career, creating a space into which one or more of the attacking midfielders advanced. As the distinction between centre-forward and attacking midfielder dissolved, Roma’s formation became, if not a 4-6-0, then certainly a 4-1-5-0.

Their experiment was taken on, slightly surprisingly, by the team that had beaten them 7-1 in the previous season’s Champions League: Manchester United. With Cristiano Ronaldo, Wayne Rooney, Carlos Tevez and Ryan Giggs or Nani slung in front of a holding pair of two from Owen Hargreaves, Michael Carrick, Anderson and Paul Scholes, United regularly have no obvious front-man, with the front four taking it in turns to become the

de facto

striker, which helps explain Ronaldo’s remarkable goals return. It is a system that requires much work to develop a mutual understanding - as was shown by United’s lack of goals in the early games of the season, and by the desperate use of the defender John O’Shea as a makeshift target-man as they struggled to find fluency in drawing 0-0 against Reading on the opening day of the 2007-08 season - but when it does click it can produce exhilarating football.

Fluidity is all. Gianni Brera’s insight in his report on the first World Cup final remains just as true today as it was then. Assuming a rough parity of ability, the team that wins will almost certainly be the one that best balances attacking fluency with defensive solidity, and in the pursuit of that the centre-forward may be the next casualty. Even Makélélé, whose uncomplicated discipline at the back of midfield was so key to Chelsea’s success under Mourinho, and the loss of whom did so much to undermine Real Madrid, has seen himself usurped at Chelsea by Mikel Jon Obi, a far more complete midfielder. As system has replaced individuality, the winger has gone and been reincarnated in a different, more complex form; so too has the playmaker; and so, now, might the striker be refined out of existence. The future, it seems, is universality.

Epilogue

∆∇ It would be easy to survey modern football and insist there can be nothing new. Roberto Mancini, in fact, did just that at a lecture he gave in Belgrade in 2007, arguing that future advances in football would come not in tactics but in the physical preparation of players. To an extent he is probably right. Football is a mature game that has been examined and analysed relentlessly for almost a century and a half, and, assuming the number of players remains constant at eleven, there probably is no revolution waiting to astonish the world. Even if there is, even if some coach in some unlikely corner happens upon some radical departure, it will not have the stunning impact that, say, Hungary’s withdrawn centre-forward had in the early fifties. Even that was, as I hope this book has demonstrated, part of a continuum, drawing directly from Matthias Sindelar’s interpretation of the centre-forward’s role in the Austrian

Wunderteam

, and having a parallel in Martim Francisco’s work with Vila Nova.

England could not deal in 1931 with Sindelar dropping off, British sides struggled to cope with Vsevolod Bobrov doing the same when Dinamo Moscow toured in 1945, and they were humiliated by Nándor Hidegkuti 1953. Lessons, evidently, should have been learned, but that they were not is explicable by the fact that those three examples were isolated, and spread over twenty-two years. These days Hungary’s

Aranycsapat

would not have come to London as a mystery: their successes would have been seen on television, videos would have been picked over, the movement of their players would have been analysed by computer. A tactical innovation will never again spring up as a surprise.

Besides which, a talented Hungarian coach such as Gusztav Sebes would almost certainly not be working in Hungary, but would have followed the money to western Europe. As cross-pollination between different football cultures increases, so national styles become less distinct. We are not yet homogenised, and probably never will be, but the trend is in that direction.

And yet there are always imaginations ready to defy expectation. A promoted side, particularly one with limited resources, usually adopts a defensive style. Spoil the game, the logic goes, restrict the influence of skill, reduce the number of goals likely to be scored, and a weaker team increases its chances of stealing a draw or a 1-0 win. Yet in 2006-07, Pasquale Marino, having led Catania to promotion to Serie A the previous season, had his side play a 4-3-3 with attacking full-backs and no holding midfielder. They were encouraged not to play the percentages, but to try the outrageous and the difficult. Occasionally they came unstuck - they were hammered 7-0 by Roma, for instance - but exuberance proved just as hard to play against as niggardliness. Following the murder of a policeman during rioting at the derby against Palermo in the February, Catania were banned from playing games at their home stadium, but they still finished as high as thirteenth. It wasn’t a new system, but it was a revolution of style, a rebellion against convention.

Old styles can be successfully reintroduced in new contexts, particularly in the shortened form of major tournaments. Greece, for instance, at Euro 2004, were the only team who played without a zonal-marking back four. Their coach, Otto Rehhagel, employed a

libero

with three man-markers and then added further solidity with a five-man midfield and a lone striker. ‘Rehhagel won because he posed a problem people had forgotten how to solve,’ said Andy Roxburgh. ‘It wasn’t fashionable but it was effective. They controlled matches without having control of the ball. Otto’s view was: why should he try a watered-down version of somebody else’s system? Whatever you say about his system, you have to admit that Greece got the ball into attack very quickly every time they had possession.’

France, in particular, seemed to struggle against Greece, losing 1-0 to them in the quarter-final. ‘They needed to get the ball to Thierry Henry faster,’ Roxburgh said. ‘Henry is at his most dangerous running into the centre from the left or running just left of centre. Against Greece, he drifted too wide because he wasn’t getting any space. That’s one of the things you want to do: push a threat to the touchline. Greece’s opponents weren’t used to being marked so tightly. The old method turned out to be a novelty.’

The move away from out-and-out forwards, perhaps, is something new, although - at least towards the end of the 2007-08 season - it remains tentative. Perhaps the 4-6-0 will, in time, become just as much the orthodoxy as 4-4-2 was in England until the mid-nineties, or the

libero

was in Italy until the late-eighties; perhaps it will prove merely a passing fad.

Certainly its emergence hints at the death of the old-fashioned striker in favour of something more versatile, and the move to universality, it can be said with some confidence, is an on-going trend. Then again, perhaps that simply proves Mancini’s point, and all that is actually happening is that the technicians of old are, thanks to improved nutrition and better training methods, becoming physically more imposing; if everybody is fit and powerful, then there is necessarily less demand for those players who offer little beyond their physique or their engine. If strikers are heading the way of old-school wingers and playmakers, though, then the question is who next? Centre-backs, maybe? After all, if there is no centre-forward to mark, the second centre-back in a 4-4-2 would seem as redundant as the third in a 3-5-2 playing against a lone forward.

It is hard to believe, equally, that the increasingly detailed analysis afforded by technology will not also make a difference. Computers and a knowledge of cybernetics helped Valeriy Lobanovskyi devise his system, and it stands to reason that the more sophisticated technology becomes, the more sophisticated systems will become. The biggest obstacle to that, in fact, is the egos of players. Puffed up by years of immense wages and celebrity status, are they willing, as Lobanovskyi and Arrigo Sacchi demanded, to sacrifice themselves utterly to the collective? The experience of Real Madrid in the

galacticos

era suggests not.

That, perhaps, is the other side of the paradox at which Jorge Valdano hinted when he spoke of television’s influence on the modern game: that it is the very popularity of modern football that prevents its advancement. Fans, arguably, are complicit in that. Terraces tend to conservatism, and the example of Sweden in the seventies indicates that there is a love of individualism - of football of first-order complexity, to use Tomas Petterson’s term - that exceeds the demand for victory. Argentina’s experiences as the period of

la nuestra

came to an end show just how damaging that decadence - of thought if nothing else - can be. That said, globalisation is an in-built defence; if nobody is progressing, then nobody is being left behind, so a wake-up like Argentina’s 6-1 defeat to Czechoslovakia in 1958 is unlikely, unless a country outside the footballing mainstream is suddenly blessed with a hugely gifted generation of players who can resist the lures of western European materialism long enough to submit themselves to the system of a tactically astute coach. South Korea’s success in reaching the semi-final of the 2002 World Cup is evidence of what can be achieved with rigorous organisation, even with essentially average players.

Sacchi, certainly, finds it ‘remarkable, worrying’ there has been no significant tactical development since the radical systematised approach of his AC Milan, but remains convinced evolution will continue. ‘As long as humanity exists,’ he said, ‘something new will come along. Otherwise football dies.’

Many before have hailed the end of history; none have ever been right.