Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (7 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Chapman, warning that it would take him five years to win anything, took the job only on condition he would face no such restrictions, something to which Norris reluctantly agreed. His first signing was Charlie Buchan. Sunderland valued him at £4,000, which their manager, Bob Kyle, insisted represented value for money as the inside-forward would guarantee twenty goals a season. If he was so confident, Norris replied, then the fee should be structured according to Buchan’s scoring record: a £2,000 initial payment, plus £100 for each goal scored in his first season. Kyle went along with it, Buchan scored twenty-one, and Sunderland gratefully accepted £4,100.

Not that such a thing seemed likely that September after the defeat at Newcastle. Buchan was an awkward character, who had walked out on his first day at Arsenal because he thought the kit was inadequate, and then refused to train on his second because he found a lump of congealed Vaseline in his supposedly freshly laundered sock. Some managers might have seen that as wilful obstructiveness or an unrealistic finickiness, Chapman seems rather to have regarded that as evidence of high standards. He also admired in Buchan an independence of thought about the game, something that was far from common in players of the age. John Lewis, a former referee, had noted in 1914 that ‘our professionals evince no great anxiety to learn anything of the theory of the sport… In most teams there is no evidence of pre-conceived tactics or thought-out manoeuvres,’ and, for all Chapman’s efforts to encourage debate, not much had changed.

Buchan had argued from the beginning of the season that the change in the offside rule meant the centre-half had to take on a more defensive role, and it was notable that in Arsenal’s defeat at St James’ the Newcastle centre-half Charlie Spencer had stayed very deep. He had offered little in an attacking sense, but had repeatedly broken up Arsenal attacks almost before they had begun, allowing Newcastle to dominate possession and territory. Chapman, at last, was convinced, but the mystery is why, given his natural inclination to the counter-attack, he had not done so earlier. He was not a man readily cowed by authority, but perhaps the FA’s words after the 1922 Cup final, coupled with his recognition of what they had done for him in lifting his life ban, had had an effect.

Arsenal were certainly not the first club to come to the conclusion that the centre-half had to become a third back, but where they did break new ground was in recognising the knock-on effect this would have at the other end of the pitch. Buchan argued, and Chapman agreed, that withdrawing the centre-half left a side short of personnel in midfield, and so proposed that he should drop back from his inside-right position, which would have created a very loose and slightly unbalanced 3-3-4.

Chapman, though, valued Buchan’s goal-scoring abilities too highly to compromise them and so instead gave the role of withdrawn inside-forward to Andy Neil. Given Neil was a third-team player, that came as something of a surprise, but it proved an inspired choice and an emphatic endorsement of Chapman’s ability to conceptualise and compartmentalise, to recognise what specific skills were needed where. Tom Whittaker, who went on to become Chapman’s trusted number two, recalled his boss describing Neil as being ‘as slow as a funeral’ but insisting it didn’t matter because ‘he has ball-control and can stand with his foot on the ball while making up his mind’.

With Jack Butler asked to check his creative instincts to play as the deep-lying centre-half, the new system had an immediate effect and, two days after the debacle at Newcastle, Arsenal, with Buchan re-enthused by the change of shape, beat West Ham 4-1 at Upton Park. They went on to finish second behind Huddersfield that season, at the time the highest league position ever achieved by a London club. The next season, though, began poorly, partly because success had brought over-confidence, and partly because opposing sides had begun to exploit Butler’s lack of natural defensive aptitude. Some argued for a return to the traditional 2-3-5, but Chapman decided the problem was rather that the revolution had not gone far enough: what was needed at centre-half was a player entirely without pretension. He found him, characteristically unexpectedly, in the form of Herbie Roberts, a gangling ginger-haired wing-half he signed from Oswestry Town for £200.

According to Whittaker, ‘Roberts’s genius came from the fact that he was intelligent and, even more important, that he did what he was told.’ He may have been one dimensional, but it was a dimension that was critical. His job, Whittaker wrote, was ‘to intercept all balls down the middle, and either head them or pass them short to a team-mate. So you see how his inability to kick a ball hard or far was camouflaged.’ Bernard Joy, the last amateur to play for England and later a journalist, joined Arsenal in 1935 as Roberts’ deputy. ‘He was a straightforward sort of player,’ Joy wrote in

Forward Arsenal!

, ‘well below Butler in technical skill, but physically and temperamentally well suited to the part he had to play. He was content to remain on the defensive, using his height to nod away the ball with his red-haired head and he had the patience to carry on unruffled in the face of heavy pressure and loud barracking. This phlegmatic outlook made him the pillar of the Arsenal defence and set up a new style that was copied all over the world.’ And that, in a sense, was the problem. Arsenal became hugely successful, and their style was aped by sides without the players or the wherewithal to use it as anything other than a negative system.

Arsenal lost the FA Cup final to Cardiff in 1927, but it was after Norris had left in 1929 following an FA inquiry into financial irregularities that success really arrived. Buchan had retired in 1928 and it was his replacement, the diminutive Scot Alex James, signed from Preston for £9,000, who made Chapman’s system come alive. The club’s official history cautions that nobody should underestimate James’s contribution to the successful Arsenal side of the 1930s. He was simply the key man.’ Economic of movement, he was supremely adept at finding space to receive the ball - preferably played rapidly from the back - and had the vision and the technique then to distribute it at pace to the forwards. Joy called him ‘the most intelligent player I played with… On the field he had the knack of thinking two or three moves ahead. He turned many a game by shrewd positioning near his own penalty area and the sudden use of a telling pass into the opponents’ weak point.’

By the time Arsenal won the FA Cup in 1930 - their first silverware, as Chapman had promised, coming in the fifth season after his arrival - the new formation had taken clear shape. The full-backs marked the wingers rather than inside-forwards, the wing-halves sat on the opposing inside-forwards rather than on the wingers, the centre-half, now a centre-back, dealt with the centre-forward, and both inside-forwards dropped deeper: the 2-3-5 had become a 3-2-2-3; the W-M.

‘The secret,’ Joy wrote, ‘is not attack, but counter-attack… We planned to make the utmost use of each individual, so that we had a spare man at each moment in each penalty area. Commanding the play in midfield or packing the opponents’ penalty area is not the object of the game… We at Arsenal achieved our end by deliberately drawing on the opponents by retreating and funnelling to our own goal, holding the attack at the limits of the penalty box, and then thrusting quickly away by means of long passes to our wingers.’

Trophies and modernisation tumbled on together, the one seeming to inspire the other. The FA, instinctively conservative, blocked moves to introduce shirt numbers and floodlit matches, but other innovations were implemented. Arsenal’s black socks were replaced by blue-and-white hoops, a clock was installed at Highbury, Gillespie Road tube station was renamed Arsenal, white sleeves were added to their red shirts in the belief that white was seen more easily in peripheral vision than any other colour and, perhaps most tellingly, after training on Fridays, Chapman had his players gather round a magnetic tactics board to discuss the coming game and sort out any issues hanging over from the previous fixture. At Huddersfield he had encouraged players to take responsibility for their positioning on the field; at Arsenal he instituted such debates as part of the weekly routine. ‘Breaking down old traditions,’ a piece in the

Daily Mail

explained, ‘he was the first manager who set out methodically to organise the winning of matches.’

It worked. Arsenal won the league in 1931 and 1933, and were beaten in the 1932 Cup final only by a highly controversial goal. Glanville wrote of them ‘approaching the precision of a machine’, and in their rapid transition from defence to attack, the unfussy functionalism of their style, there was a sensibility in keeping with the art deco surrounds of Highbury. The ‘machine’ analogy is telling, recalling as it does Le Corbusier’s reference to a house as ‘a machine for living in’; this was modernist football. William Carlos Williams, similarly, in a phrase that would become almost a slogan for his version of modernism, described a poem as ‘a machine made of words … there can be no part, as in any other machine, that is redundant.’ Chapman’s Arsenal were very much of their age. ‘It was,’ Joy said of their style, ‘twentieth-century, terse, exciting, spectacular, economic, devastating.’

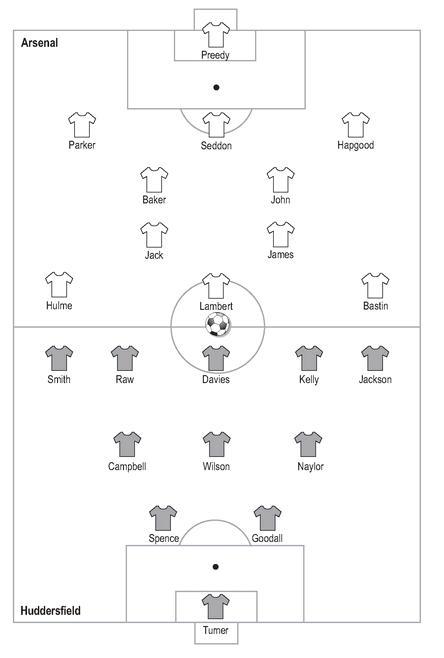

Arsenal 2 Huddersfield Town 0, FA Cup final, Wembley, London, 26 April 1930

Perhaps that is not surprising. Chapman was, after all, part of the first wave of beneficiaries of Forster’s Education Act of 1870, which made schooling compulsory to the age of twelve and allowed unprecedented numbers of working-class men to fill the managerial vacancies opened up by the First World War. They may not have had Ezra Pound’s command to ‘make it new’ ringing in their ears, but it is fair to suggest that the new managerial class was more open to innovation than its tradition-bound predecessors. Chapman, it is worth remembering, was a near contemporary of another modernist genius of Nottinghamshire mining stock, D.H. Lawrence.

Within football there were doubters, perhaps the most astute of them Carruthers in the

Daily Mail

, who, after the 1933 championship, commented: ‘If it were thought that other clubs would try to copy them, their example might, I’m afraid, be unfortunate. There is only one Arsenal today, and I cannot conceive another simply because no other club has players fit to carry on the same ideas.’

The ideas, anyway, were imperfectly understood, as was demonstrated when England’s selection committee picked Roberts for a friendly against Scotland in 1931. He was the first stopper to be called up for his country, but neither of the full-backs, Fred Goodall and Ernie Blenkinsop, were accustomed to the W-M. As a result, Scotland ‘picnicked happily in the open spaces’ as L.V. Manning put it in the

Daily Sketch

, winning 2-0.

In Scotland, opinion was just as divided between those who recognised the efficacy of the more modern system, and those who remained romantically tied to the short passing game. The last hurrah of the pattern-weaving approach came on 31 March 1928 when the Scotland side who would become immortalised as the ‘Wembley Wizards’ hammered England, Alex Jackson scoring three and Alex James two in a 5-1 win. In his report in

The Evening News

, Sandy Adamson described Jackson’s first goal as ‘a zigzag advance which ought to go down in posterity as a classic of its kind’ and went on to describe how ‘exultant Scots engaged in cat-and-mouse cantrips… From toe to toe the ball sped. The distracted enemy was bewildered, baffled and beaten. One bit of weaving embraced eleven passes and not an Englishman touched the sphere until [Tim] Dunn closed the movement with a sky-high shot over the bar…’

The

Glasgow Herald

was more restrained. ‘The success of the Scots,’ its report said, ‘was primarily another demonstration that Scottish skill, science and trickery will still prevail against the less attractive and simpler methods of the English style in which speed is relied upon as the main factor.’ Jimmy Gibson and Jimmy McMullan, the wing-halves, and Dunn and James, the inside-forwards, clearly did combine to devastating effect on a wet pitch, but it should be borne in mind that the game was effectively a playoff for the wooden spoon in the Home International championship. The supposedly self-evident superiority of the Scottish style hadn’t been apparent in the 1-0 defeat to Northern Ireland or the 2-2 draw against Wales.

It is significant too that eight of the Scotland eleven were based at English clubs: for all their passing ability, it evidently helped to have players used to the pace of the English game. Stylistically, anyway, this was not quite the throw-back some would suggest. Tom Bradshaw, the centre-half, was given a defensive role, marking Dixie Dean, so while they may not have been playing a full-blown W-M, nor was their system a classic 2-3-5.

The W-M’s arrival in the club game was patchy. The former Rangers player George Brown recalls a charity game between a Rangers-Celtic XI and a Hearts-Hibs XI from ‘about 1930’: ‘Davie Meiklejohn was at right-half, I was at left-half and Celtic’s Jimmy McStay was at centre-half,’ he said. ‘Things did not go very well for us in the first half and by the interval we were one goal down. So during half-time, Meiklejohn said to McStay, “All the trouble is coming through the middle because you are too far up the field. We play with Jimmy Simpson well back and this leaves the backs free.” McStay agreed to try this and we eventually ran out comfortable winners. So from then on he played the same type of game for Celtic.’ Like Jack Butler at Arsenal, though, McStay was no natural defender, and a run of nine seasons without a title was brought to an end only when the stopper centre-half Willie Lyon was signed from Queen’s Park.