Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (10 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

What is certainly true is that he made full use of the prevailing militarism to dominate and motivate his side. ‘More than one selector leads to compromise,’ he said, ‘and no great football team was ever built on that.’ He was an astute man-manager, developing a stern, paternalistic style to deal with players often idolised by fans of their clubs. He would, for instance, referee all practice games played in training, and if he felt a player had refused to pass to a team-mate because of some private grudge, he would send him off. If he picked two players who were known not to get on, he would force them to room together. It was his nationalism, though, that was most controversial. On the way to Budapest for a friendly against Hungary that Italy won 5-0, to take just one example, he made his players visit the First World War battlefields of Oslavia and Gorizia, stopping at the monumental cemetery at Redupiglia. ‘I told them it was good that the sad and terrible spectacle might have struck them: that whatever would be asked of us on that occasion was nothing compared with those that had lost their lives on those surrounding hills,’ he wrote in his autobiography. At other times, he would march at the head of his players singing ‘

Il Piave

’.

For all that, Pozzo was Anglophile enough to hark back to a golden age of fair play, fretting about the deleterious effects of the win-bonuses that soon became a feature of the national league. ‘It is win at all costs,’ he said. ‘It is the bitter grudge against the adversary, it is the preoccupation of the result to the ends of the league table.’ He inclined, similarly, to a classical 2-3-5, but he lacked a centre-half of sufficient mobility and creativity to play the formation well. Pozzo turned instead to Luisito Monti, who had played for Argentina in the 1930 World Cup. He joined Juventus in 1931, and became one of the

oriundi

, the South American players who, thanks to Italian heritage, qualified to play for their adopted country. Already thirty when he signed, Monti was overweight and, even after a month of solitary training, was not quick. He was, though, fit, and became known as ‘

Doble ancho

’ (‘Double-wide’) for his capacity to cover the ground. Pozzo, perhaps influenced by a formation that had already come into being at Juventus, used him as a

centro mediano

, a halfway house - not quite Charlie Roberts, but certainly not Herbie Roberts either. He would drop when the other team had possession and mark the opposing centre-forward, but would advance and become an attacking fulcrum when his side had the ball. Although he was not a third back - Glanville, in fact, says it was only in 1939 with an article Bernardini wrote after Pozzo’s side had drawn 2-2 against England in Milan that the full implications of the W-M (the

sistema

, as Pozzo called it, as opposed to the traditional

metodo

) were fully appreciated in Italy - he played deeper than a traditional centre-half, and so the two inside-forwards retreated to support the wing-halves. The shape was thus a 2-3-2-3, a W-W. At the time it seemed, as the journalist Mario Zappa put it in

La Gazzetta della Sport

, ‘a model of play that is the synthesis of the best elements of all the most admired systems.’

Shape is one thing, style is another, and Pozzo, despite his qualms, was fundamentally pragmatic. That he had a technically accomplished side is not in doubt, as they proved, before Monti had been called into the side, in a 3-0 victory over Scotland in 1931. ‘The men are fast,’ the

Corriere della Sera

reported of the hapless tourists, ‘athletically well prepared, and seem sure enough in kicking and heading, but in classic play along the ground, they look like novices.’ That would be stern enough criticism for any side, but for players brought up in the finest pattern-weaving traditions, it is damning.

Back then, the great centre-forward Giuseppe Meazza, who had made his debut in 1930, was regularly compared to a bull-fighter, while a popular song of the time claimed ‘he scored to the rhythm of the foxtrot’. That sense of fun and élan, though, was soon to fade. Meazza remained a stylish forward, and there was no doubting the quality of the likes of Silvio Piola, Raimundo Orsi and Gino Colaussi, but physicality and combativeness became increasingly central. ‘In the tenth year of the fascist era,’ an editorial in

Lo Stadia

noted in 1932, ‘the youth are toughened for battle, and for the fight, and more for the game itself; courage, determination, gladiatorial pride, chosen sentiments of our race, cannot be excluded.’

Pozzo was also one of the earliest exponents of man-marking, a sign that football had become not merely about a side playing its own game, but about stopping the opposition playing theirs. In a friendly against Spain in Bilbao in 1931, for instance, he had Renato Cesarini mark Ignacío Aguirrezabala on the logic that ‘if I succeeded in cutting off the head with which the eleven adversaries thought, the whole system would collapse’.

That raised concerns among the purists, but it was at the 1934 World Cup that questions really began to be asked about the ethics of Pozzo’s Italy. Having drawn 1-1 with England - who were still persisting in their policy of isolation - a year earlier, Italy, playing at home, were always going to be among the favourites, particularly given the sense that the

Wunderteam

was past its peak. For once Meisl’s pessimism seemed justified as he complained of the absence of Hiden, his goalkeeper, and of players exhausted by foreign tours with their club sides, although he also claimed, apparently accepting the English criticism that his side lacked punch, that if he could have borrowed the Arsenal centre-forward Cliff Bastin, they could have walked to victory.

Italy and Austria, Pozzo and Meisl, met in the semi-final, but by then the tournament had already begun to slink into disrepute. Austria were far from innocent, having been involved in a brawl in their quarter-final victory over Hungary, but it was the 1-1 draw between Italy and Spain at the same stage that marked the descent of the tournament into violence. Monti, for all his ability, was quite prepared to indulge in the darker arts, while Ricardo Zamora, the Spain goalkeeper, was battered so frequently that he was unable to play in the replay the following day. Sources vary on whether three or four Spaniards were forced to leave the field through injury, but whichever, Spain were left feeling aggrieved as a diving header from Meazza gave Italy a 1-0 win.

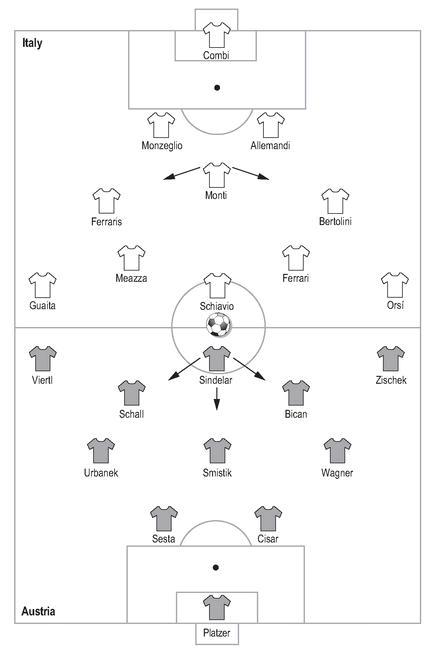

The anticipated clash of styles in the semi-final was a damp squib. Sindelar was marked out of the game by Monti, Austria failed to have shot in the first forty minutes, and Italy won by a single goal, Meazza bundling into Hiden’s replacement, Peter Platzer, and Enrique Guaita, another of the

oriundi

, forcing the loose ball over the line. It was left to Czechoslovakia, who had beaten Germany in the other semi, to defend the honour of the Danubian School. At times they threatened to embarrass Italy, and took a seventy-sixth minute lead through Antonín Puc. Frantisek Svoboda hit a post and Jirí Sobotka missed another fine chance but, with eight minutes remaining, Orsi equalised with a drive that swerved freakishly past Frantisek Plánicka. Seven minutes into extra-time, a limping Meazza crossed from the right, Guaita helped it on and Angelo Schiavio, who later spoke of having been driven by ‘the strength of desperation’, beat Josef Ctyroky to fire in the winner. Mussolini’s Italy had the victory it so desired, but elsewhere the strength of that desire and the methods to which they were prepared to stoop to achieve it left a sour taste. ‘In the majority of countries the world championship was called a sporting fiasco,’ the Belgian referee John Langenus said, ‘because beside the will to win all sporting considerations were non-existent and because, moreover, a certain spirit brooded over the whole championship.’

A meeting with England that November - the so-called ‘Battle of Highbury’ - only confirmed the impression, as Italy reacted badly after Monti broke a bone in his foot in a second-minute challenge with Ted Drake. ‘For the first quarter of an hour there might just as well not have been a ball on the pitch as far as the Italians were concerned,’ said Stanley Matthews. ‘They were like men possessed, kicking anything and everything that moved.’ England capitalised on their indiscipline to take a 3-0 lead, but after Pozzo had calmed his side at half-time, they played stirringly to come back to 3-2 in the second half.

Italy 1 Austria 0, World Cup semi-final, San Siro, Milan, 3 June 1934

Beneath the aggression and the cynicism, Italy were unquestionably talented, and they retained the World Cup in 1938 with what Pozzo believed was his best side. Again, the focus was on defensive solidity. ‘The big secret of the Italian squad is its capacity to attack with the fewest amount of men possible, without ever distracting the half-backs from their defensive work,’ Zappa wrote. Austria had been subsumed by Germany by then, but a team formed by the two semi-finalists of the previous competition fared poorly, and lost after a replay to Karl Rappan’s Switzerland in the first round. Czechoslovakia went out to Brazil in the last eight, but Hungary progressed to the final for the last showdown between the Danubian School and Pozzo. Italy proved too quick and too athletic and, with Michele Andreolo, another

oriundo

who had replaced Monti as the

centro mediano

, keeping a check on György Sárosi, the Hungarian centre-forward, Meisl’s conception of the game was made to look sluggish and old-fashioned. It did not pass without lament - ‘How shall we play the game?’ the French journalist Jean Eskenazi asked. ‘As though we are making love or catching a bus?’ - but pass it did.

As Sindelar reached the end of his career and with Meisl ageing, the Danubian style of football may have faded away anyway, but political developments made sure of it. With the Anschluss came the end of the central European Jewish intelligentsia, the end of the spirit of the coffee house and the death of Sindelar. As the thirties went on, the great centre-forward had increasingly withdrawn from the national team, but he allowed himself to be picked for what was dubbed a ‘Reconciliation Game’ between an Ostmark XI and an all-German line-up on 3 April 1938.

Football in Germany was not so advanced as in Austria, but it was improving. Otto Nerz, first national coach, who was appointed on 1 July 1926, was an early advocate of the W-M, but something of Hogan’s teaching lived on through Schalke 04, who reached nine of the ten championship playoff finals between 1933 and 1942, winning six. Their coach, Gustav Wieser, was an Austrian, and under him they practised a version of the whirl that became known as ‘

der Kreisel

’ - the spinning-top. According to the defender Hans Bornemann, it was not the man with the ball, but those out of possession running into space who determined the direction of their attacks. ‘It was only when there was absolutely nobody left you could pass the ball to that we finally put it into the net,’ he said. Hogan may have admired their style, but he would have questioned their ethos.

Such excess troubled Nerz, and he refused to pick both Schalke’s feted inside-forwards, Ernst Kuzorra and Fritz Szepan, for the national team. (He did, in fact, call up Szepan for the 1934 World Cup, but bafflingly played him at centre-half.) ‘Nerz,’ Kuzorra explained, ‘said to me: “Let me tell you something: your odds and ends football at Schalke, all that passing around, doesn’t impress me one bit. If you and Szepan play together it’ll just be fiddling and dribbling around.”’

Germany were semi-finalists in Italy in 1934, which encouraged thoughts that they might win gold on home soil at the 1936 Olympics. Instead they lost, humiliatingly, 2-0 to Norway in what, unfortunately for Nerz, was the only football match Hitler ever attended.

Sepp Herberger, an assistant to Nerz and the man who would lead West Germany to victory at the 1954 World Cup, was not at the game, having gone to watch Italy play Japan in another quarter-final. He was eating a dinner of knuckle of pork and sauerkraut at the team camp when another coach brought him news of Germany’s defeat. Herberger pushed his plate away and never touched knuckle of pork again. He succeeded Nerz after the tournament, and immediately switched to a more Danubian model, bringing in Adolf Urban and Rudi Gellesch from Schalke and deploying the elegant, hard-drinking Mannheim inside-forward Otto Siffling as a central striker. The result was a team of greater flexibility that reached its peak on 16 May 1937 with an 8-0 friendly victory over Denmark in Breslau (what is ow Wroclaw). ‘The robot style people like to pin on Germany sank into the realm of legend,’ the journalist Gerd Krämer wrote. ‘Artistic football triumphed.’

ow Wroclaw). ‘The robot style people like to pin on Germany sank into the realm of legend,’ the journalist Gerd Krämer wrote. ‘Artistic football triumphed.’