Irish Fairy Tales (16 page)

“I am no party to this untimely journey,” he said angrily.

“Let it be so,” said Becfola.

She left the palace with one maid, and as she crossed the doorway something happened to her, but by what means it happened would be hard to tell; for in the one pace she passed out of the palace and out of the world, and the second step she trod was in Faery, but she did not know this.

Her intention was to go to Cluain da chaillech to meet Crimthann, but when she left the palace she did not remember Crimthann any more.

To her eye and to the eye of her maid the world was as it always had been, and the landmarks they knew were about them. But the object for which they were travelling was different, although unknown, and the people they passed on the roads were unknown, and were yet people that they knew.

They set out southwards from Tara into the Duffry of Leinster, and after some time they came into wild country and went astray. At last Becfola halted, saying:

“I do not know where we are.”

The maid replied that she also did not know.

“Yet,” said Becfola, “if we continue to walk straight on we shall arrive somewhere.”

They went on, and the maid watered the road with her tears.

Night drew on them; a grey chill, a grey silence, and they were enveloped in that chill and silence; and they began to go in expectation and terror, for they both knew and did not know that which they were bound for.

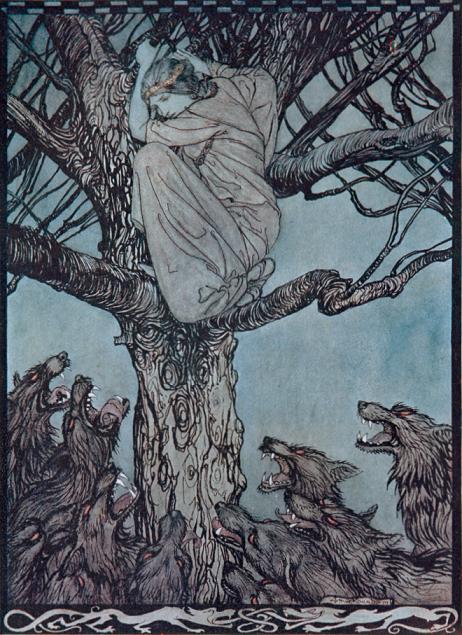

As they toiled desolately up the rustling and whispering side of a low hill the maid chanced to look back, and when she looked back she screamed and pointed, and clung to Becfola's arm. Becfola followed the pointing finger, and saw below a large black mass that moved jerkily forward.

“Wolves!” cried the maid.

“Run to the trees yonder,” her mistress ordered. “We will climb them and sit among the branches.”

They ran then, the maid moaning and lamenting all the while.

“I cannot climb a tree,” she sobbed, “I shall be eaten by the wolves.”

And that was true.

But her mistress climbed a tree, and drew by a hand's breadth from the rap and snap and slaver of those steel jaws. Then, sitting on a branch, she looked with angry woe at the straining and snarling horde below, seeing many a white fang in those grinning jowls, and the smouldering, red blink of those leaping and prowling eyes.

She looked with angry woe at the straining and snarling horde below

Chapter 3

B

ut after some time the moon arose and the wolves went away, for their leader, a sagacious and crafty chief, declared that as long as they remained where they were, the lady would remain where she was; and so, with a hearty curse on trees, the troop departed.

Becfola had pains in her legs from the way she had wrapped them about the branch, but there was no part of her that did not ache, for a lady does not sit with any ease upon a tree.

For some time she did not care to come down from the branch. “Those wolves may return,” she said, “for their chief is crafty and sagacious, and it is certain, from the look I caught in his eye as he departed, that he would rather taste of me than eat any woman he has met.”

She looked carefully in every direction to see if she might discover them in hiding; she looked closely and lingeringly at the shadows under distant trees to see if these shadows moved; and she listened on every wind to try if she could distinguish a yap or a yawn or a sneeze.

But she saw or heard nothing; and little by little tranquillity crept into her mind, and she began to consider that a danger which is past is a danger that may be neglected.

Yet ere she descended she looked again on the world of jet and silver that dozed about her, and she spied a red glimmer among distant trees.

“There is no danger where there is light,” she said, and she thereupon came from the tree and ran in the direction that she had noted.

In a spot between three great oaks she came upon a man who was roasting a wild boar over a fire. She saluted this youth and sat beside him. But after the first glance and greeting he did not look at her again, nor did he speak.

When the boar was cooked he ate of it and she had her share. Then he arose from the fire and walked away among the trees. Becfola followed, feeling ruefully that something new to her experience had arrived; “For,” she thought, “it is usual that young men should not speak to me now that I am the mate of a king, but it is very unusual that young men should not look at me.”

But if the young man did not look at her she looked well at him, and what she saw pleased her so much that she had no time for further cogitation. For if Crimthann had been beautiful, this youth was ten times more beautiful. The curls on Crimthann's head had been indeed as a benediction to the queen's eye, so that she had eaten the better and slept the sounder for seeing him. But the sight of this youth left her without the desire to eat, and, as for sleep, she dreaded it, for if she closed an eye she would be robbed of the one delight in time, which was to look at this young man, and not to cease looking at him while her eye could peer or her head could remain upright.

They came to an inlet of the sea all sweet and calm under the round, silver-flooding moon, and the young man, with Becfola treading on his heel, stepped into a boat and rowed to a high-jutting, pleasant island. There they went inland towards a vast palace, in which there was no person but themselves alone, and there the young man went to sleep, while Becfola sat staring at him until the unavoidable peace pressed down her eyelids and she too slumbered.

She was awakened in the morning by a great shout.

“Come out, Flann, come out, my heart!”

The young man leaped from his couch, girded on his harness, and strode out. Three young men met him, each in battle harness, and these four advanced to meet four other men who awaited them at a little distance on the lawn. Then these two sets of four fought together with every warlike courtesy but with every warlike severity, and at the end of that combat there was but one man standing, and the other seven lay tossed in death.

Becfola spoke to the youth.

“Your combat has indeed been gallant,” she said.

“Alas,” he replied, “if it has been a gallant deed it has not been a good one, for my three brothers are dead and my four nephews are dead.”

“Ah me!” cried Becfola, “why did you fight that fight?”

“For the lordship of this island, the Isle of Fedach, son of Dall.”

But, although Becfola was moved and horrified by this battle, it was in another direction that her interest lay; therefore she soon asked the question which lay next her heart:

“Why would you not speak to me or look at me?”

“Until I have won the kingship of this land from all claimants, I am no match for the mate of the High King of Ireland,” he replied.

And that reply was like balm to the heart of Becfola.

“What shall I do?” she inquired radiantly.

“Return to your home,” he counselled. “I will escort you there with your maid, for she is not really dead, and when I have won my lordship I will go seek you in Tara.”

“You will surely come,” she insisted.

“By my hand,” quoth he, “I will come.”

These three returned then, and at the end of a day and night they saw far off the mighty roofs of Tara massed in the morning haze. The young man left them, and with many a backward look and with dragging, reluctant feet, Becfola crossed the threshold of the palace, wondering what she should say to Dermod and how she could account for an absence of three days' duration.

Chapter 4

I

t was so early that not even a bird was yet awake, and the dull grey light that came from the atmosphere enlarged and made indistinct all that one looked at, and swathed all things in a cold and livid gloom.

As she trod cautiously through dim corridors Becfola was glad that, saving the guards, no creature was astir, and that for some time yet she need account to no person for her movements. She was glad also of a respite which would enable her to settle into her home and draw about her the composure which women feel when they are surrounded by the walls of their houses, and can see about them the possessions which, by the fact of ownership, have become almost a part of their personality. Sundered from her belongings, no woman is tranquil, her heart is not truly at ease, however her mind may function, so that under the broad sky or in the house of another she is not the competent, precise individual which she becomes when she sees again her household in order and her domestic requirements at her hand.

Becfola pushed the door of the king's sleeping chamber and entered noiselessly. Then she sat quietly in a seat gazing on the recumbent monarch, and prepared to consider how she should advance to him when he awakened, and with what information she might stay his inquiries or reproaches.

“I will reproach him,” she thought. “I will call him a bad husband and astonish him, and he will forget everything but his own alarm and indignation.”

But at that moment the king lifted his head from the pillow and looked kindly at her.

Her heart gave a great throb, and she prepared to speak at once and in great volume before he could formulate any question. But the king spoke first, and what he said so astonished her that the explanation and reproach with which her tongue was thrilling fled from it at a stroke, and she could only sit staring and bewildered and tongue-tied.

“Well, my dear heart,” said the king, “have you decided not to keep that engagement?”

“IâIâ !” Becfola stammered.

“It is truly not an hour for engagements,” Dermod insisted, “for not a bird of the birds has left his tree; and,” he continued maliciously, “the light is such that you could not see an engagement even if you met one.”

“I,” Becfola gasped. “Iââ!”

“A Sunday journey,” he went on, “is a notoriously bad journey. No good can come from it. You can get your smocks and diadems to-morrow. But at this hour a wise person leaves engagements to the bats and the staring owls and the round-eyed creatures that prowl and sniff in the dark. Come back to the warm bed, sweet woman, and set out on your journey in the morning.”

Such a load of apprehension was lifted from Becfola's heart that she instantly did as she had been commanded, and such a bewilderment had yet possession of her faculties that she could not think or utter a word on any subject.

Yet the thought did come into her head as she stretched in the warm gloom that Crimthann the son of Ae must be now attending her at Cluain da chaillech, and she thought of that young man as of something wonderful and very ridiculous, and the fact that he was waiting for her troubled her no more than if a sheep had been waiting for her or a roadside bush.

She fell asleep.

Chapter 5

I

n the morning as they sat at breakfast four clerics were announced, and when they entered the king looked on them with stern disapproval.

“What is the meaning of this journey on Sunday?” he demanded.

A lank-jawed, thin-browed brother, with uneasy, intertwining fingers, and a deep-set, venomous eye, was the spokesman of those four.

“Indeed,” he said, and the fingers of his right hand strangled and did to death the fingers of his left hand, “indeed, we have transgressed by order.”

“Explain that.”

“We have been sent to you hurriedly by our master, Molasius of Devenish.”

“A pious, a saintly man,” the king interrupted, “and one who does not countenance transgressions of the Sunday.”

“We were ordered to tell you as follows,” said the grim cleric, and he buried the fingers of his right hand in his left fist, so that one could not hope to see them resurrected again.

“It was the duty of one of the Brothers of Devenish,” he continued, “to turn out the cattle this morning before the dawn of day, and that Brother, while in his duty, saw eight comely young men who fought together.”

“On the morning of Sunday,” Dermod exploded.

The cleric nodded with savage emphasis.