Irish Fairy Tales (20 page)

“No!”

“I won't build house or hut for the sake of passing one night here, for I hope never to see this place again.”

“I'Il build a house myself,” said the Carl, “and the man who does not help in the building can stay outside of the house.”

The Carl stumped to a near-by wood, and he never rested until he had felled and tied together twenty-four couples of big timber. He thrust these under one arm and under the other he tucked a bundle of rushes for his bed, and with that one load he rushed up a house, well thatched and snug, and with the timber that remained over he made a bonfire on the floor of the house.

His companion sat at a distance regarding the work with rage and aversion.

“Now, Cael, my darling,” said the Carl, “if you are a man help me to look for something to eat, for there is game here.”

“Help yourself,” roared Cael, “for all that I want is not to be near you.”

“The tooth that does not help gets no helping,” the other replied.

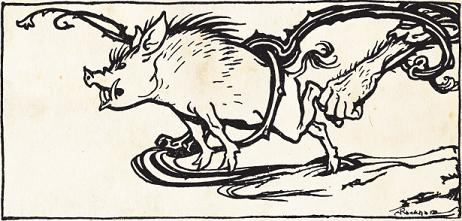

In a short time the Carl returned with a wild boar which he had run down. He cooked the beast over his bonfire and ate one half of it, leaving the other half for his breakfast. Then he lay down on the rushes, and in two turns he fell asleep.

But Cael lay out on the side of the hill, and if he went to sleep that night he slept fasting. It was he, however, who awakened the Carl in the morning.

“Get up, beggarman, if you are going to run against me.”

The Carl rubbed his eyes.

“I never get up until I have had my fill of sleep, and there is another hour of it due to me. But if you are in a hurry, my delight, you can start running now with a blessing. I will trot on your track when I waken up.”

Cael began to race then, and he was glad of the start, for his antagonist made so little account of him that he did not know what to expect when the Carl would begin to run.

“Yet,” said Cael to himself, “with an hour's start the beggarman will have to move his bones if he wants to catch on me,” and he settled down to a good, pelting race.

Chapter 5

A

t the end of an hour the Carl awoke. He ate the second half of the boar, and he tied the unpicked bones in the tail of his coat. Then with a great rattling of the boar's bones he started.

It is hard to tell how he ran or at what speed he ran, but he went forward in great two-legged jumps, and at times he moved in immense one-legged, mud-spattering hops, and at times again, with wide-stretched, far-flung, terrible-tramping, space-destroying legs he ran.

He left the swallows behind as if they were asleep. He caught up on a red deer, jumped over it, and left it standing. The wind was always behind him, for he outran it every time; and he caught up in jumps and bounces on Cael of the Iron, although Cael was running well, with his fists up and his head back and his two legs flying in and out so vigorously that you could not see them because of that speedy movement.

Trotting by the side of Cael, the Carl thrust a hand into the tail of his coat and pulled out a fistfull of red bones.

“Here, my heart, is a meaty bone,” said he, “for you fasted all night, poor friend, and if you pick a bit off the bone your stomach will get a rest.”

“Keep your filth, beggarman,” the other replied, “for I would rather be hanged than gnaw on a bone that you have browsed.”

“Why don't you run, my pulse?” said the Carl earnestly; “why don't you try to win the race?”

Cael then began to move his limbs as if they were the wings of a fly, or the fins of a little fish, or as if they were the six legs of a terrified spider.

“I am running,” he gasped.

“But try and run like this,” the Carl admonished, and he gave a wriggling bound and a sudden outstretching and scurrying of shanks, and he disappeared from Cael's sight in one wild spatter of big boots.

Despair fell on Cael of the Iron, but he had a great heart.

“I will run until I burst,” he shrieked, “and when I burst, may I burst to a great distance, and may I trip that beggarman up with my burstings and make him break his leg.”

He settled then to a determined, savage, implacable trot.

He caught up on the Carl at last, for the latter had stopped to eat blackberries from the bushes on the road, and when he drew nigh, Cael began to jeer and sneer angrily at the Carl.

“Who lost the tails of his coat?” he roared.

“Don't ask riddles of a man that's eating blackberries,” the Carl rebuked him.

“The dog without a tail and the coat without a tail,” cried Cael.

“I give it up,” the Carl mumbled.

“It's yourself, beggarman,” jeered Cael.

“I am myself,” the Carl gurgled through a mouthful of blackberries, “and as I am myself, how can it be myself? That is a silly riddle,” he burbled.

“Look at your coat, tub of grease!”

The Carl did so.

“My faith,” said he, “where are the two tails of my coat?”

“I could smell one of them and it wrapped around a little tree thirty miles back,” said Cael, “and the other one was dishonouring a bush ten miles behind that.”

“It is bad luck to be separated from the tails of your own coat,” the Carl grumbled. “I'll have to go back for them. Wait here, beloved, and eat blackberries until I come back, and we'll both start fair.”

“Not half a second will I wait,” Cael replied, and he began to run towards Ben Edair as a lover runs to his maiden or as a bee flies to his hive.

“I haven't had half my share of blackberries either,” the Carl lamented as he started to run backwards for his coat-tails.

He ran determinedly on that backward journey, and as the path he had travelled was beaten out as if it had been trampled by an hundred bulls yoked neck to neck, he was able to find the two bushes and the two coat-tails. He sewed them on his coat.

Then he sprang up, and he took to a fit and a vortex and an exasperation of running for which no description may be found. The thumping of his big boots grew as continuous as the pattering of hailstones on a roof, and the wind of his passage blew trees down. The beasts that were ranging beside his path dropped dead from concussion, and the steam that snored from his nose blew birds into bits and made great lumps of cloud fall out of the sky.

The thumping of his big boots grew as continuous as the pattering of hailstones on a roof, and the wind of his passage blew trees down

He again caught up on Cael, who was running with his head down and his toes up.

“If you won't try to run, my treasure,” said the Carl, “you will never get your tribute.”

And with that he incensed and exploded himself into an eye-blinding, continuous waggle and complexity of boots that left Cael behind him in a flash.

“I will run until I burst,” sobbed Cael, and he screwed agitation and despair into his legs until he hummed and buzzed like a bluebottle on a window.

Five miles from Ben Edair the Carl stopped, for he had again come among blackberries.

He ate of these until he was no more than a sack of juice, and when he heard the humming and buzzing of Cael of the Iron he mourned and lamented that he could not wait to eat his fill. He took off his coat, stuffed it full of blackberries, swung it on his shoulders, and went bounding stoutly and nimbly for Ben Edair.

Chapter 6

I

t would be hard to tell of the terror that was in Fionn's breast and in the hearts of the Fianna while they attended the conclusion of that race.

They discussed it unendingly, and at some moment of the day a man upbraided Fionn because he had not found Caelte the son of Ronán as had been agreed on.

“There is no one can run like Caelte,” one man averred.

“He covers the ground,” said another.

“He is light as a feather.”

“Swift as a stag.”

“Lunged like a bull.”

“Legged like a wolf.”

“He runs!”

These things were said to Fionn, and Fionn said these things to himself.

With every passing minute a drop of lead thumped down into every heart, and a pang of despair stabbed up to every brain.

“Go,” said Fionn to a hawk-eyed man, “go to the top of this hill and watch for the coming of the racers.”

And he sent lithe men with him so that they might run back in endless succession with the news.

The messengers began to run through his tent at minute intervals calling “nothing,” “nothing,” “nothing,” as they paused and darted away.

And the words, “nothing, nothing, nothing,” began to drowse into the brains of every person present.

“What can we hope from that Carl?” a champion demanded savagely.

“Nothing,” cried a messenger who stood and sped.

“A clump!” cried a champion.

“A hog!” said another.

“A flat-footed,”

“Little-winded,”

“Big-bellied,”

“Lazy-boned,”

“Pork!”

“Did you think, Fionn, that a whale could swim on land, or what did you imagine that lump could do?”

“Nothing,” cried a messenger, and was sped as he spoke.

Rage began to gnaw in Fionn's soul, and a red haze danced and flickered before his eyes. His hands began to twitch and a desire crept over him to seize on champions by the neck, and to shake and worry and rage among them like a wild dog raging among sheep.

He looked on one, and yet he seemed to look on all at once.

“Be silent,” he growled. “Let each man be silent as a dead man.”

And he sat forward, seeing all, seeing none, with his mouth drooping open, and such a wildness and bristle lowering from that great glum brow that the champions shivered as though already in the chill of death, and were silent.

He rose and stalked to the tent-door.

“Where to, O Fionn?” said a champion humbly.

“To the hill-top,” said Fionn, and he stalked on.

They followed him, whispering among themselves, keeping their eyes on the ground as they climbed.

Chapter 7

W

hat do you see?” Fionn demanded of the watcher.

“Nothing,” that man replied.

“Look again,” said Fionn.

The eagle-eyed man lifted a face, thin and sharp as though it had been carven on the wind, and he stared forward with an immobile intentness.

“What do you see?” said Fionn.

“Nothing,” the man replied.

“I will look myself,” said Fionn, and his great brow bent forward and gloomed afar.

The watcher stood beside, staring with his tense face and unwinking, lidless eye.

“What can you see, O Fionn?” said the watcher.

“I can see nothing,” said Fionn, and he projected again his grim, gaunt forehead. For it seemed as if the watcher stared with his whole face, aye, and with his hands; but Fionn brooded weightedly on distance with his puckered and crannied brow.