Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (30 page)

Read Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia Online

Authors: David Vine

Tags: #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #General

After days of negotiations, the Mauritian Government finally convinced the group to disembark. The government paid adults Rs5, children Rs3, and gave nineteen families what turned out to be dilapidated apartments, amid pigs, cows, and other farm animals, in the slums of Port Louis. Twelve other families found their own housing, crowding into the shacks of relatives and friends.

2

“In ’72, I was deported,” described Aurélie Lisette Talate, one of the last to go. “I left Diego—Diego was closed,” in 1971. After that she was sent to Peros Banhos before her final deportation. “In ’72, I left Peros. I went via Seychelles.”

“I came to Mauritius with six children and my mother,” Aurélie said. “I arrived in Mauritius in November. November ’72 we got our house near the Bois Marchand cemetery, but the house didn’t have a door, didn’t have running water, didn’t have electricity.”

A stick-thin woman in her sixties, Aurélie eats little, smokes a lot, and speaks with a power that earned her the nickname

ti piman

—little chili pepper: In Mauritius the littlest chilies are the hottest and the fiercest.

“The way we were treated wasn’t the kind of treatment that people need to be able to live. And then my children and I began to suffer. All my children started getting sick.”

Within two months of arriving in Mauritius, two of Aurélie’s children had died. The second was buried in an unmarked grave because she lacked the money to pay for a burial. “We didn’t have any more money. The government buried him, and to this day, I don’t know where he’s buried.”

In the first years in exile, most of the islanders’ anger was directed at the Mauritian Government and Prime Minister Ramgoolam, who were understood to have “sold” Chagos and the Chagossians to Britain in exchange for Mauritian independence.

Mauritians “committed more than a crime,” Aurélie said. They “deracinated us. Sold Diego so that Mauritius could get its independence. We lived there. We lost our houses,” and suddenly in Mauritius “we had none. We were living like animals. Land? We had none. . . . Work? We had none. Our children weren’t going to school. . . . I say to everyone, I say to them, ‘Yes, the English deceived me.’”

A tradition of resistance among Chagossians started in 1968 when some of the first islanders prevented from returning to their homes protested to the Mauritian Government, demanding that they be returned to Chagos. From the beginning of what they came to call

lalit chagossien

—the Chagossian struggle—women have been at the forefront of the movement, protesting in the streets, rallying supporters, going on hunger strikes, confronting the police and getting arrested.

The 1975 petition delivered to the British and U.S. governments cited failed promises of compensation made by British agents in Chagos. “Here in Mauritius, everything has to be bought and everything is expensive. We don’t have money and we don’t have work.” Owing to “sorrow, poverty, and lack of food and care,” they said, “we have at least 40 persons who have died” in exile. The Chagossians asked the British Government to “urge” the Mauritian Government to provide land, housing, and jobs or return them to their islands. “Although we were poor” in Chagos, they wrote, “we were not dying of hunger. We were living free.”

3

The petition and numerous other pleas to the governments of Britain, the United States, Mauritius, and the Seychelles went unheeded. The U.S. Government declared it had “no legal responsibility” for the islanders;

4

the following year, a British official sent to investigate found the islanders “living in deplorable conditions.” Both governments did nothing.

5

In 1978, after years of protests and pressure, the Government of Mauritius finally paid compensation to some of the islanders from the £650,000 it had received from the British Government in 1972. When the money proved “hopelessly inadequate,”

6

Aurélie and several other Chagossian women went on what would be the first of five hunger strikes over four

years to protest their conditions. The protesters demanded proper housing: “Give us a house; if not, return us to our country, Diego,” proclaimed one of their flyers.

7

The hunger strike lasted 21 days in an office of the Mauritian Militant Party (MMM), a leftist opposition party whose leaders had assisted the struggle since the first arrivals in 1968. Later that year, four Chagossians were jailed for resisting the police when Mauritian authorities tore down their shacks.

8

Both protests yielded few concrete results but added to mounting political momentum for the islanders.

In 1979, with MMM assistance, several Chagossians engaged a British lawyer, Bernard Sheridan, to negotiate with the British Government about providing additional compensation. Sheridan was already suing the United Kingdom on behalf of Michel Vincatassin, a Chagossian who charged that he had been forcibly removed from his and his ancestors’ homeland.

British officials reportedly offered £1.25 million in additional compensation to the group on the condition that Vincatassin drop his case and Chagossians sign deeds “in full and final settlement,” waiving future suits and “all our claims and rights (if any) of whatsoever nature to return to the British Indian Ocean Territory.”

9

Sheridan came to Mauritius offering the money in exchange for the renunciation deeds. Initially many impoverished Chagossians signed them—more precisely, given near universal adult illiteracy, most provided their thumbprints on deeds written in English. When Chagossian and MMM leaders heard the terms of the deal, they halted the process and sent Sheridan back to London. A support group wrote to Sheridan to explain that those who had “signed” the forms had done so without “alternative legal advice,” and “as a mere formality” to obtain desperately needed money, rather than out of agreement with its conditions. No compensation was disbursed.

RANN NU DIEGO!

Before long Chagossians were back in the streets of Mauritius, launching more hunger strikes and their largest protests yet in 1980 and 1981. Along with Aurélie, Rita was part of a group of women who guided the movement. Together they repeatedly faced police intimidation, violence, and arrest, to lead hundreds marching on the British High Commission, protesting in front of government offices, and sleeping on the streets and sidewalks of the Mauritian capital. In one notorious incident, now recounted with embarrassed glee, a group of women faced off against a line of male

riot police officers in downtown Port Louis. The police charged some of the women, hitting them with batons to get them to disperse and knocking them to the ground. Suddenly and spontaneously, a woman reached up and grabbed a cop by the testicles. “Grabbed his, grabbed his testicles, his balls! Yes!” said Aurélie. “She grabbed the cop’s balls! She grabbed his balls and then he fell to his knees.” Yelling in pain, he and other riot police ran off in full retreat.

“No one was afraid,” Rita said of the women protesters. “We weren’t afraid. They were shooting tear gas at us, so we hit back, threw rocks at them. We weren’t afraid.”

Led by women like Rita and Aurélie, the islanders demanded the right to return to Chagos as well as immediate compensation, decent housing, and jobs.

10

“We yelled, ‘Give us back Diego! Give us back Diego that you stole, Ramgoolam! That you sold, Ramgoolam!’” Aurélie recounted. “We went and we yelled in the streets: ‘Ramgoolam sold Diego! Ramgoolam, give us back Diego! Get a boat to take us to Diego!’”

For the first time, a broad coalition of Mauritian political groups and unions supported the people under the Kreol rallying cry

Rann Nu Diego

—Give Us Back Diego. The slogan served to unite the Chagossians’ struggle with the demands of many Mauritians to return Chagos to Mauritian sovereignty and close the base.

11

Ambiguity in the Kreol phrase, however, also obscured key disagreements between the groups still visible today in what are at times difficult alliances: Does

rann nu

mean “give us back” or “return us to”? Does the

us

mean Chagossians or Mauritius and the Mauritian people? And does giving back Diego mean evicting the base or only a reversion of control over the island with the base allowed to stay?

During this moment of unity, though, the coalition soon won results. Following violent clashes and the arrest of six Chagossian women and two Mauritian supporters during another eighteen-day hunger strike, Mauritian Prime Minister Seewoosagur Ramgoolam left for London to meet British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The two governments agreed to hold talks on compensation with Chagossian representatives.

After two rounds of negotiations, the British Government agreed to provide £4 million in compensation, with the Mauritian Government contributing land it valued at £1 million. In exchange, most signed or thumbprinted so-called “renunciation forms” to protect the U.K. Government from further claims for compensation and the right to return.

Many Chagossians have later disputed the legality of these forms and their knowledge of their contents, again written in English without translation. Rita explained, “I didn’t make my thumbprint to renounce my

right. I made my print to get money to give my children food. They had no food.”

Rita continued insistently, “I never renounced my right. . . . You can show me my thumbprint, my thumbprint, my signing, there was Rs8,000 for me in the bank, but I don’t know how to read. I don’t know how to write. . . . I took it because my children were dying of hunger. I was pulling food out of the trashcan to give to them. I went to buy food so I could give them food,” Rita said. “If I didn’t sign, I would have been pulling food from the trashcan again to give to my children. . . . I did not renounce my right.”

CHAGOSSIANS TAKE CHARGE

In the wake of the compensation agreement, many felt that their interests had not been well represented by some of their Mauritian allies and spokespeople. Several, including prominent Chagossian leaders and former hunger strikers Aurélie and Charlesia Alexis, created the first solely Chagossian support organization, the Chagos Refugees Group (CRG).

12

With Rita’s help, they asked her last son born in Peros Banhos, eighteenyear-old Louis Olivier Bancoult, to join the organization. The women felt their illiteracy had allowed the community’s manipulation in the past, and Olivier was one of the few community members who had gone to secondary school and was literate. “They needed a Chagossian who had some education,” he explained.

The CRG, under the leadership of Aurélie, Charlesia, Rita, and Olivier, pressed for the right to return and additional compensation. They continued their work through the 1980s and 1990s but showed little progress. Gradually they lost support among the exiles.

Another organization, the Chagossian Social Committee (CSC), eventually took charge of the people’s political struggle, led by CSC founders Fernand Mandarin and his Mauritian barrister Hervé Lassemillante. The group pursued out-of-court negotiations with the U.K., U.S., and Mauritian governments for compensation and the right to return. While the CSC had little success in pursuing substantive talks, the group gained recognition for Chagossians as an indigenous people before the UN.

13

A CSC leaflet showing Fernand participating in a session at the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations proclaims, “To live on our land of origin: A sacred right, wherever our origin may be!”

NEW APPROACHES

In 1997, two Chagossian women approached Mauritian attorney Sivakumaren Mardemootoo about bringing a lawsuit against the British Government challenging the legality of the expulsion. Mardemootoo discussed the matter with British solicitor Richard Gifford and on the strength of their case soon gained British legal aid to pursue the suit.

14

To expand the plaintiff class, Mardemootoo approached CSC leaders to ask about their joining the case. He explained to me that he heard no response from the CSC, and on the day he made his inquiry the two women instructed him to stop working on their behalf.

Gifford and Mardemootoo turned to the CRG, whose leaders had previously pursued the possibility of bringing a suit against Britain and the United States. Working closely with Olivier, who was now juggling the presidency of the CRG with his day job as an electrician for the Mauritius Central Electricity Board, the lawyers filed a 1998 lawsuit at the High Court in London.

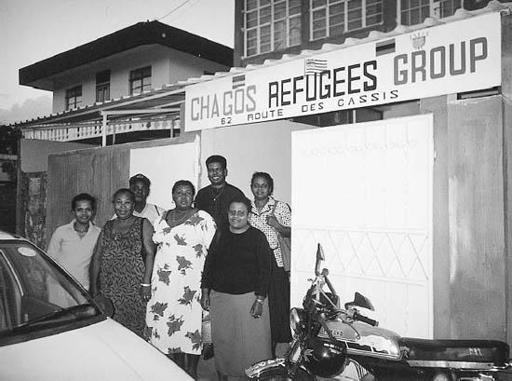

Figure 11.1 Chagos Refugees Group (CRG) members outside office (Mimose Bancoult Furcy at front right), Cassis, Mauritius, 2002. Photo by author.

Initially the CRG, which by then only had the support of a handful of Chagossians, faced considerable opposition from the CSC’s leadership and Mauritians concerned about the political and legal implications of the suit. Since Britain detached Chagos from Mauritius to create the BIOT in 1965, Mauritian political parties and citizens have criticized the detachment as illegal under the rules of decolonization and campaigned at the UN and other international forums in favor of a reversion to Mauritian sovereignty. Many Mauritians (and the CSC) believed that in suing the United Kingdom, the Chagossians were implicitly recognizing Britain’s possession of Chagos and thus damaging Mauritius’s sovereignty claim. Although Mauritian governments and political parties have at times offered various forms of high-and low-profile support to the Chagossians, they generally remained noncommittal on the issue of the suit.

15